Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

distributive vs collective

‘The injections saved her life.’

‘The goal of their actions is to find a new home.’

In virtue of what do actions involving multiple agents ever have collective goals?

Very Small Scale

Shared Agency

Small Scale

Shared Agency

Very Small Scale

Shared Agency

Playing a piano duet

Playing a chord together

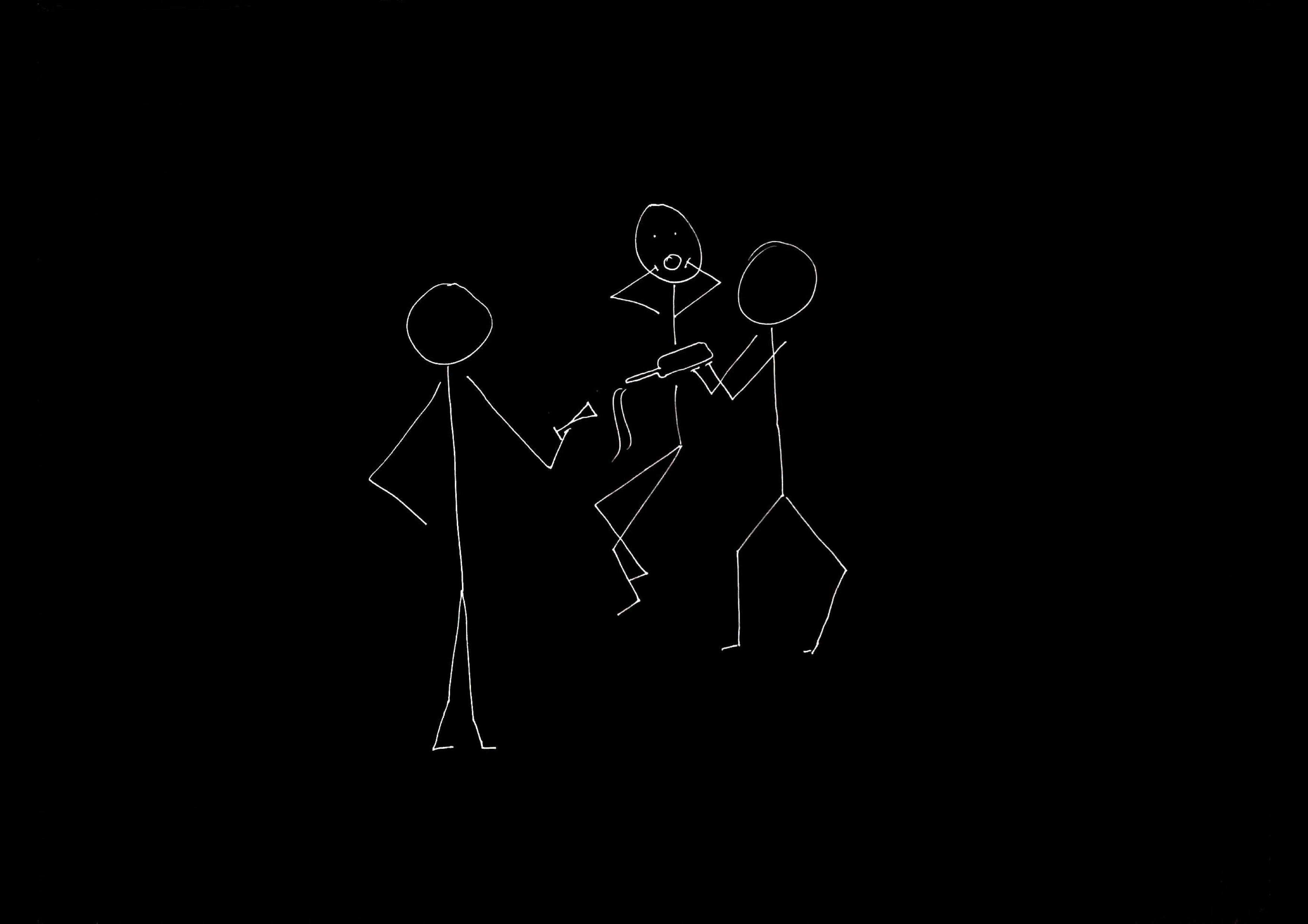

Toasting our success together

Clinking glasses

Washing up together

Passing a plate between us

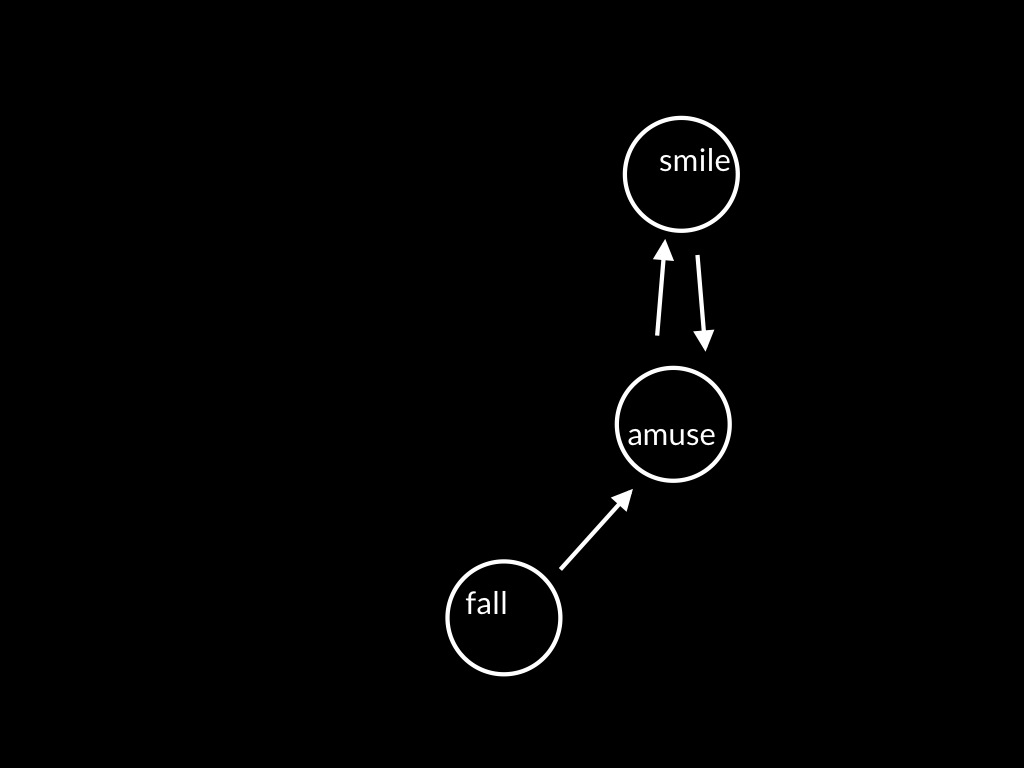

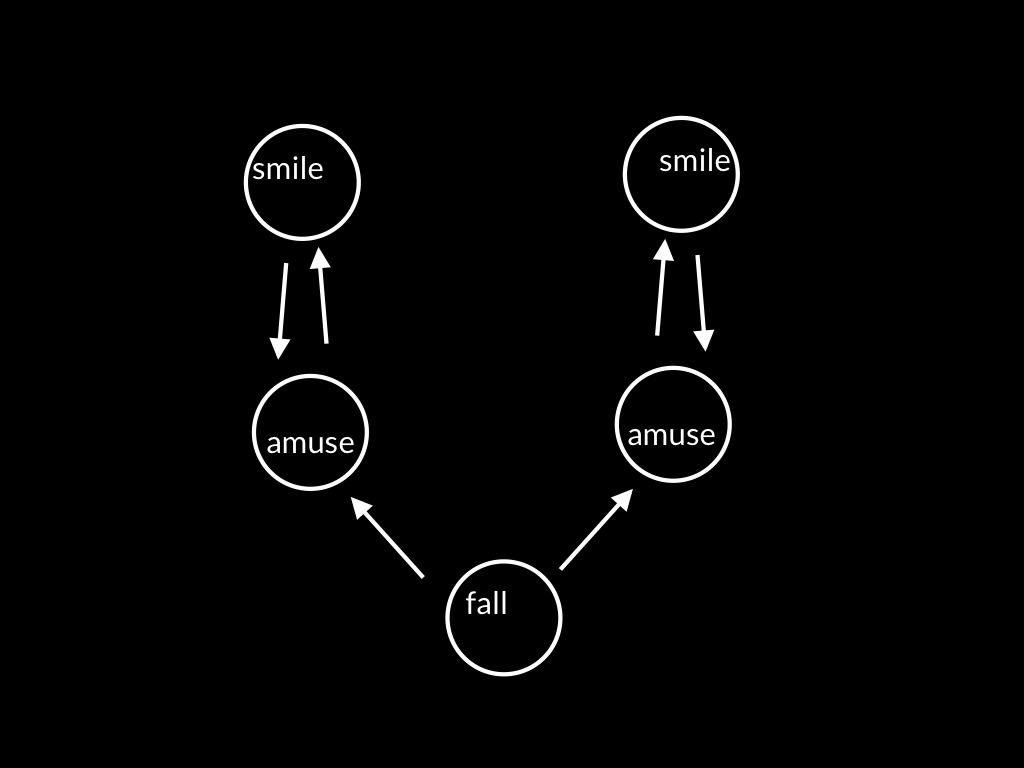

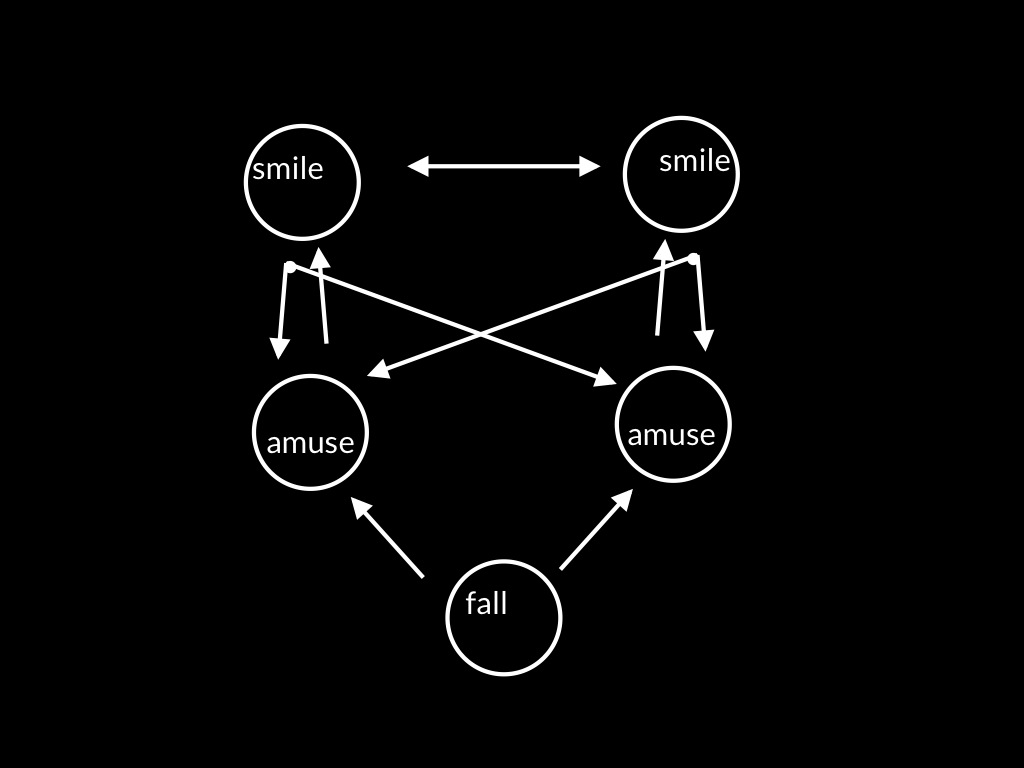

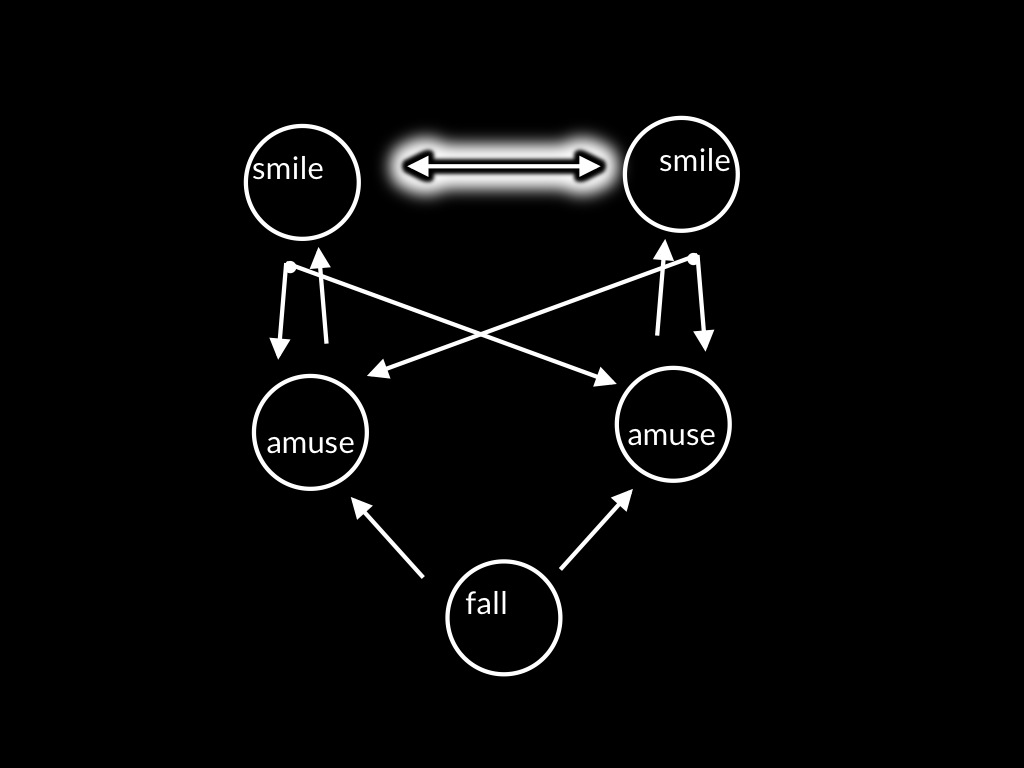

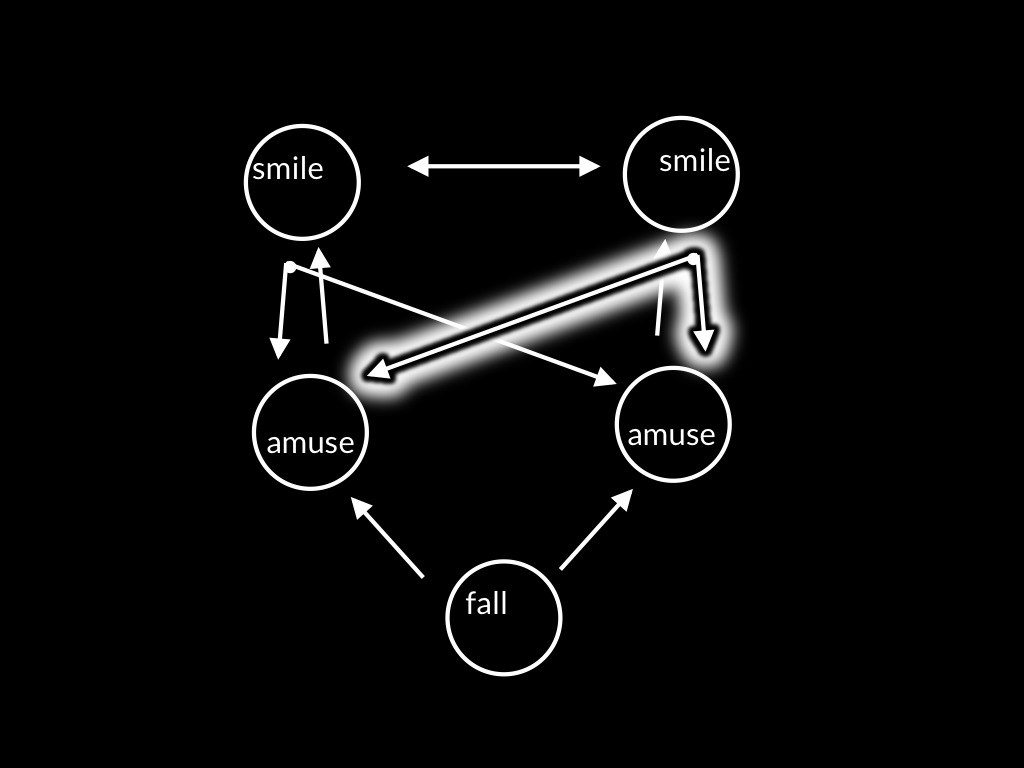

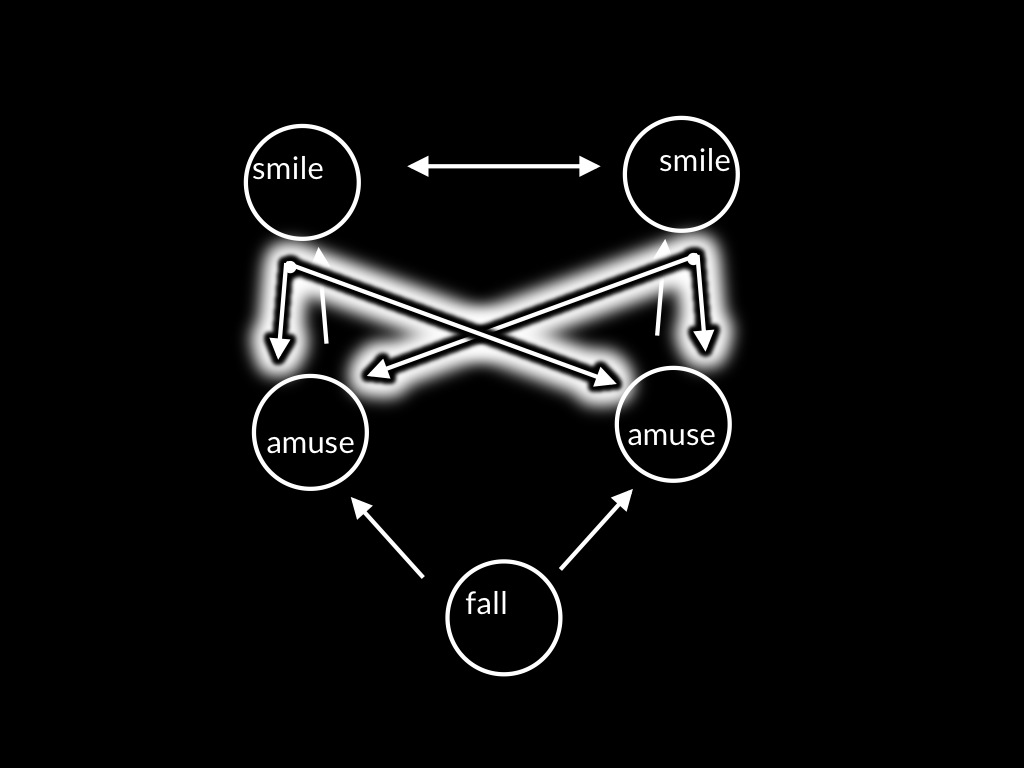

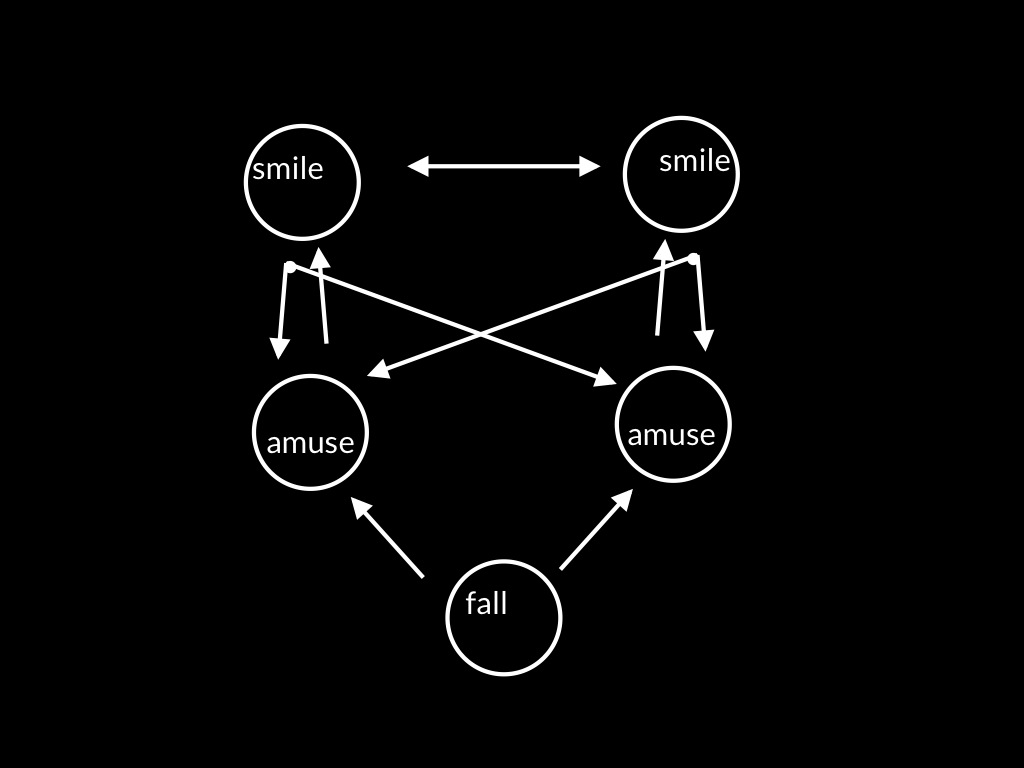

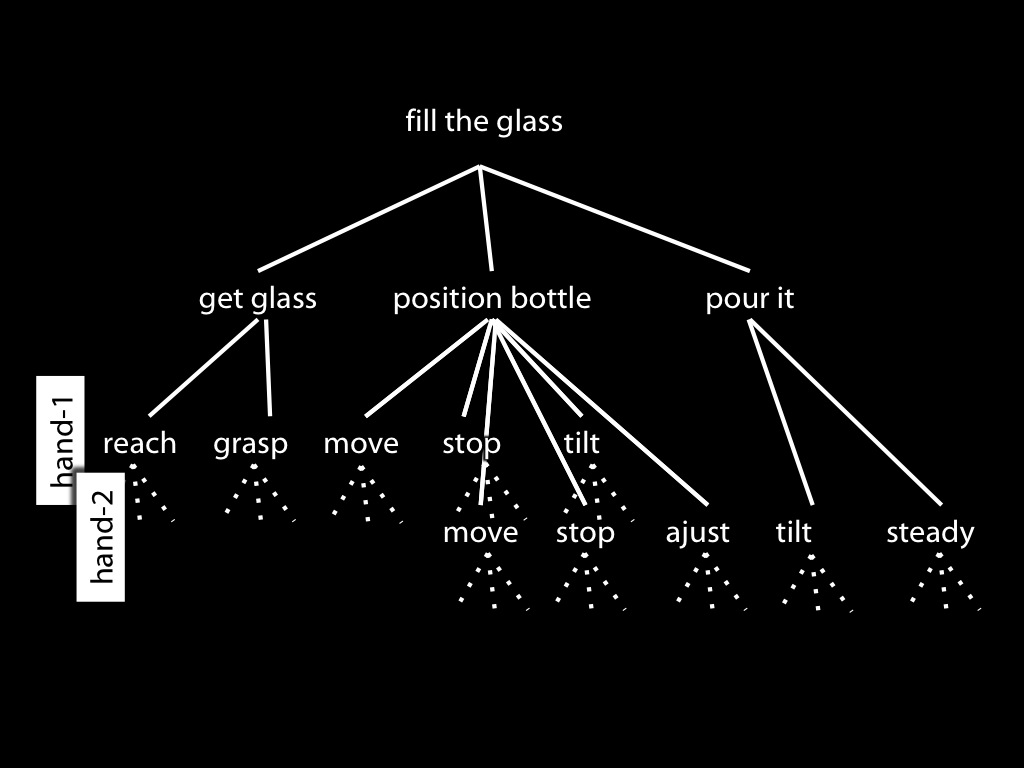

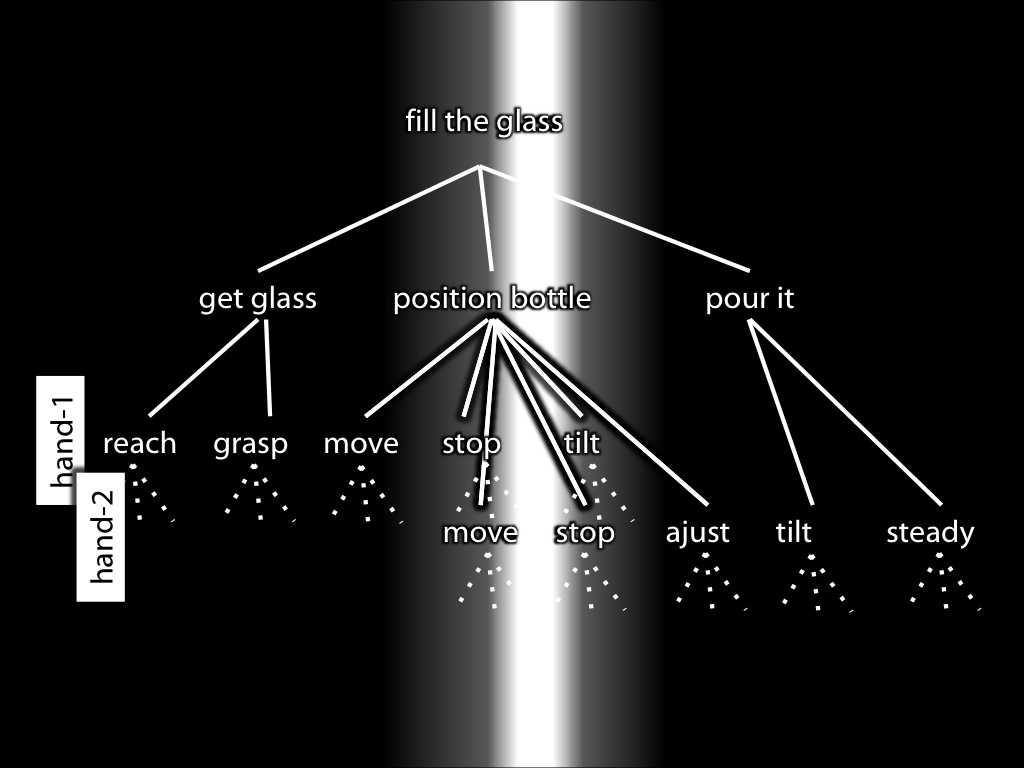

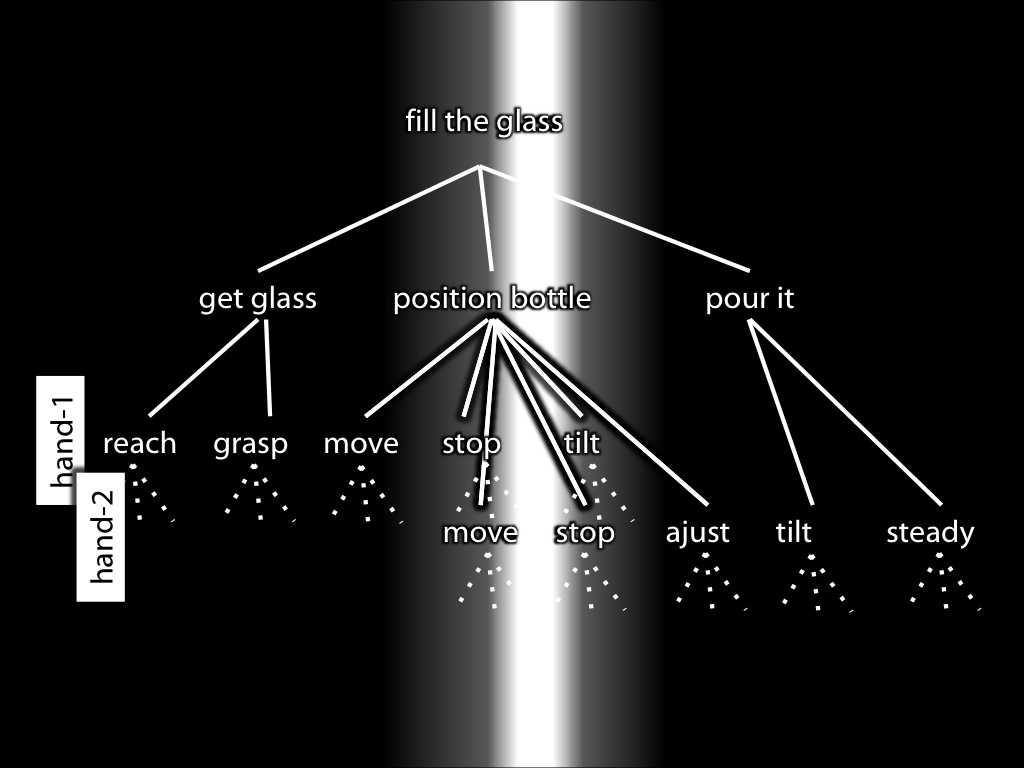

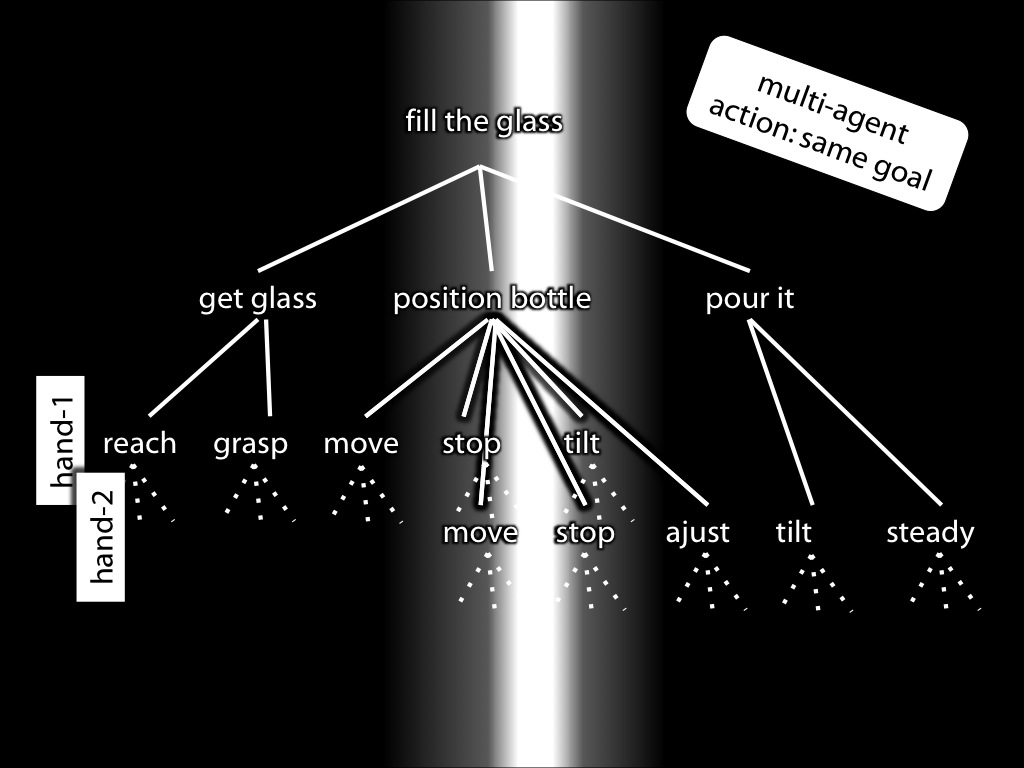

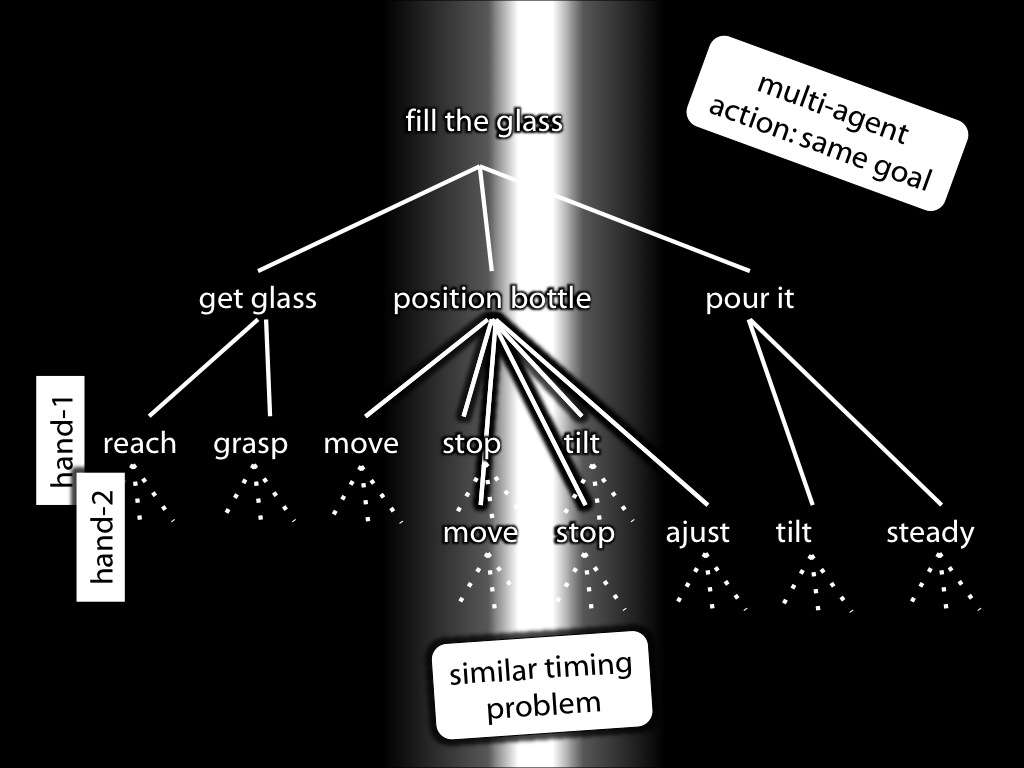

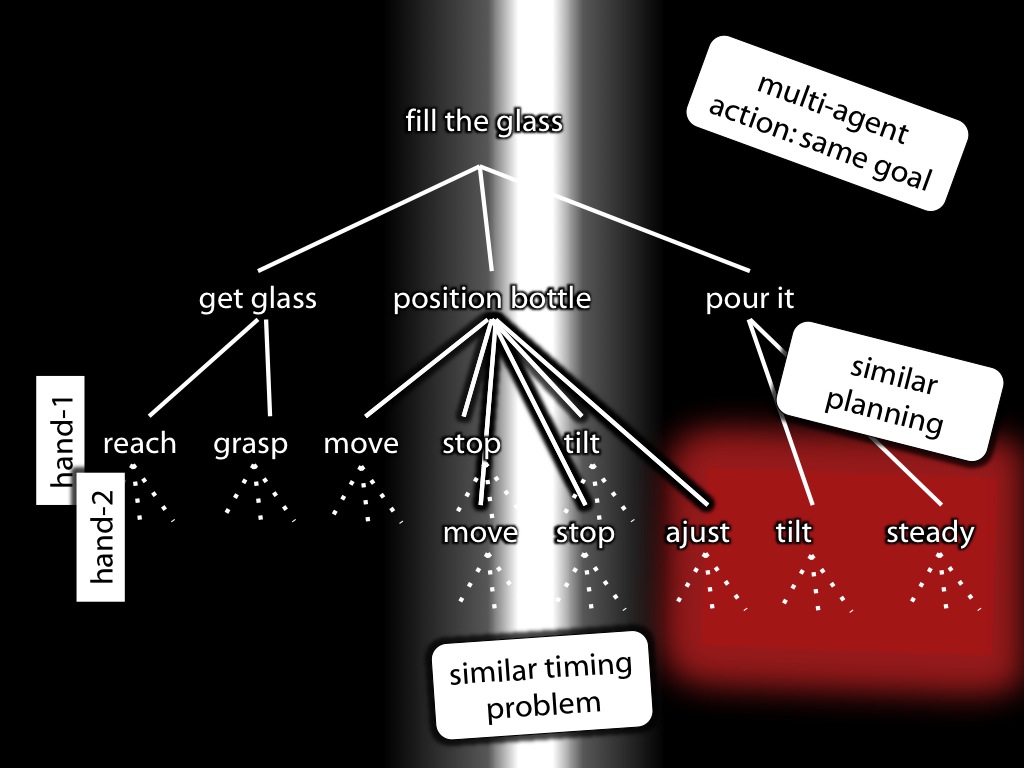

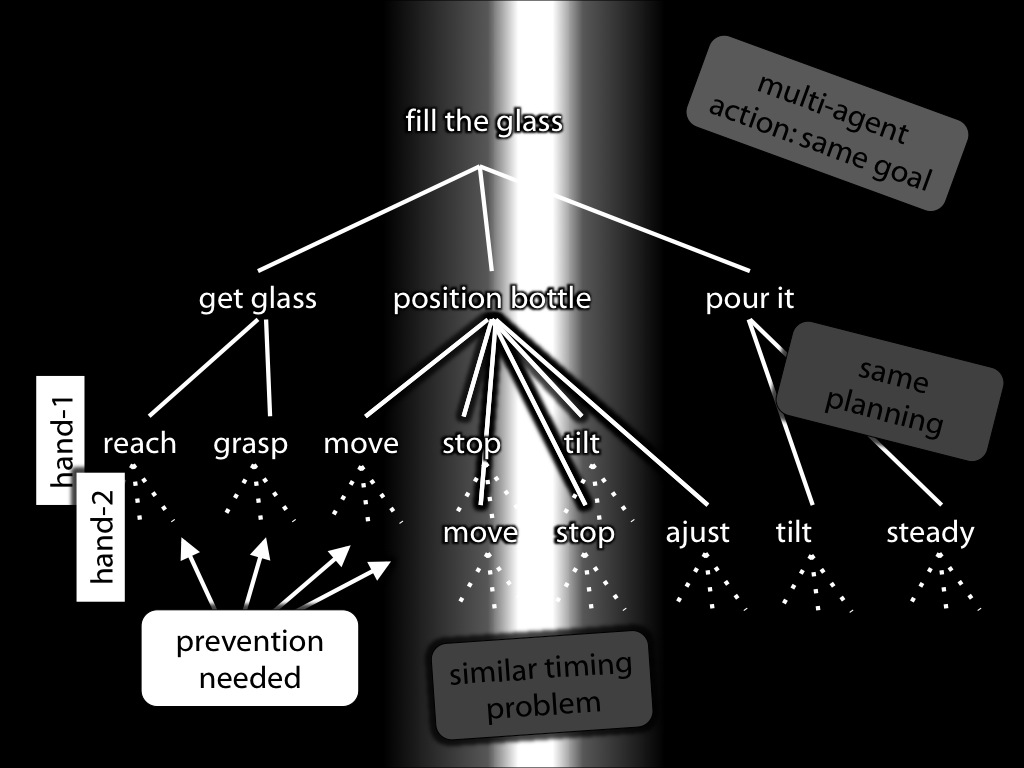

motor representations represent outcomes and trigger planning-like processes

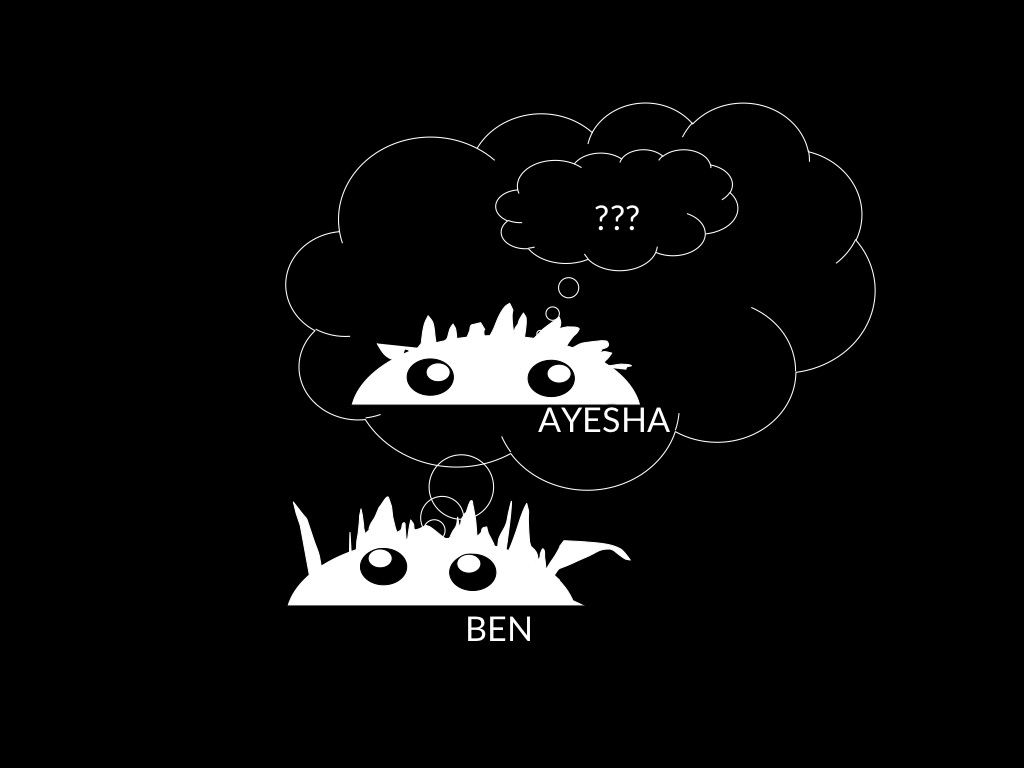

Conjecture :

collective goals are represented motorically

I.e. sometimes, when two or more actions involving multiple agents are, or need to be, coordinated:

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

Conjecture :

collective goals are represented motorically

I.e. sometimes, when two or more actions involving multiple agents are, or need to be, coordinated:

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

In virtue of what do actions involving multiple agents ever have collective goals?

cooperation?

Purposive actions are cooperative to the extent that, for each agent, her performing these actions rather than any other actions depends in part on how good an overall pattern of trade-offs between demandingness and well-suitedness can be achieved for all of the actions.

Where we each represent a collective goal motorically, our actions will normally be cooperative in this sense.

Limit: very small scale joint actions

break

Why motor representation?

‘informal observation including self-observation’ and my ‘own sense of the matter’.

(Gilbert, 2014 pp. 24, 358)

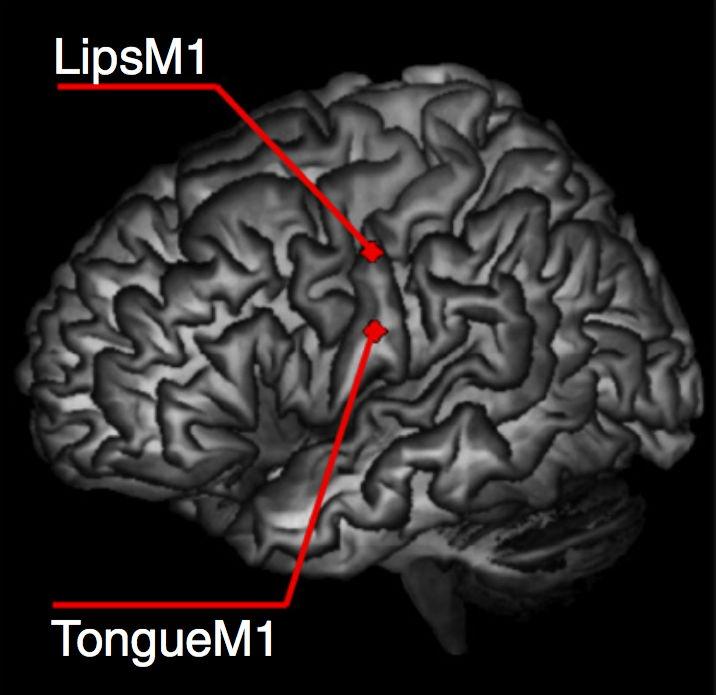

D'Ausilio et al (2009, figure 1)

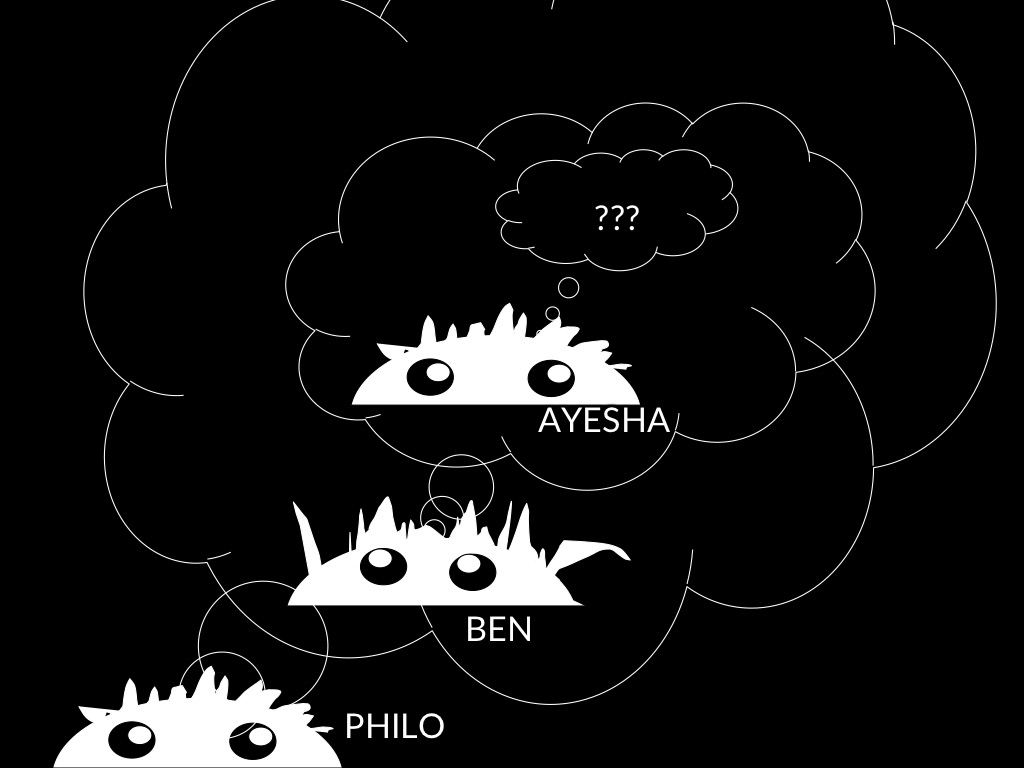

Conjecture :

collective goals are represented motorically

I.e. sometimes, when two or more actions involving multiple agents are, or need to be, coordinated:

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

In virtue of what

do very small scale joint actions

have collective goals?

Interagential structures of motor representations.

In virtue of what

are very small scale joint actions

ever trade-off cooperative?

Interagential structures of motor representations.

What about the Simple View Revised?

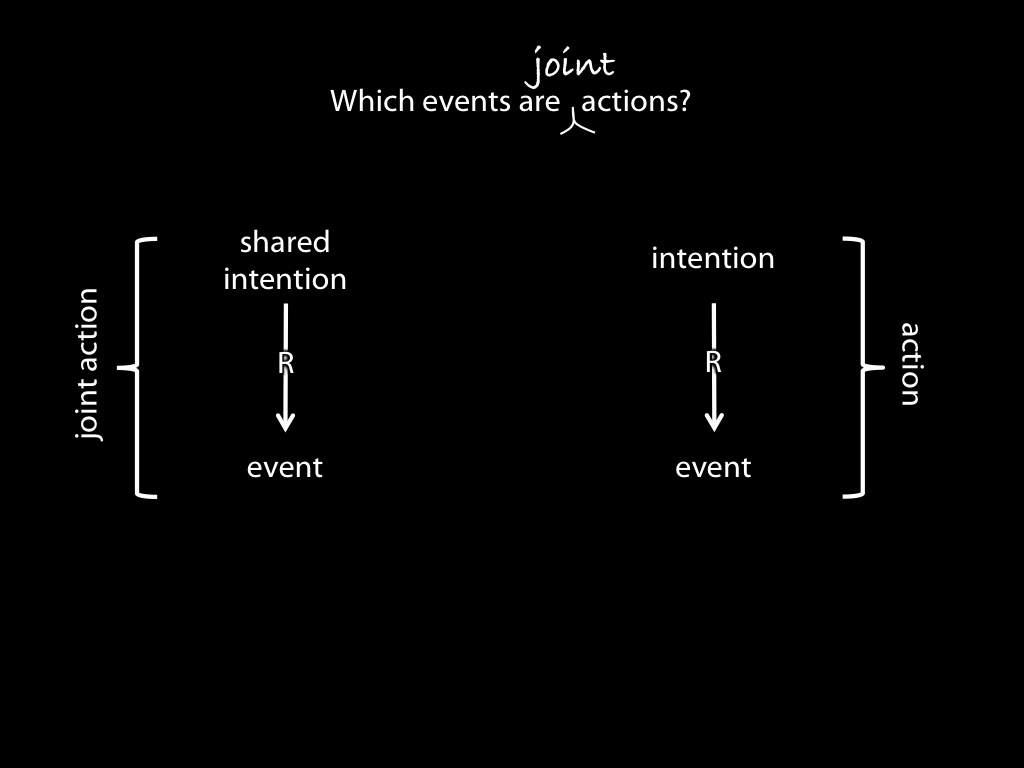

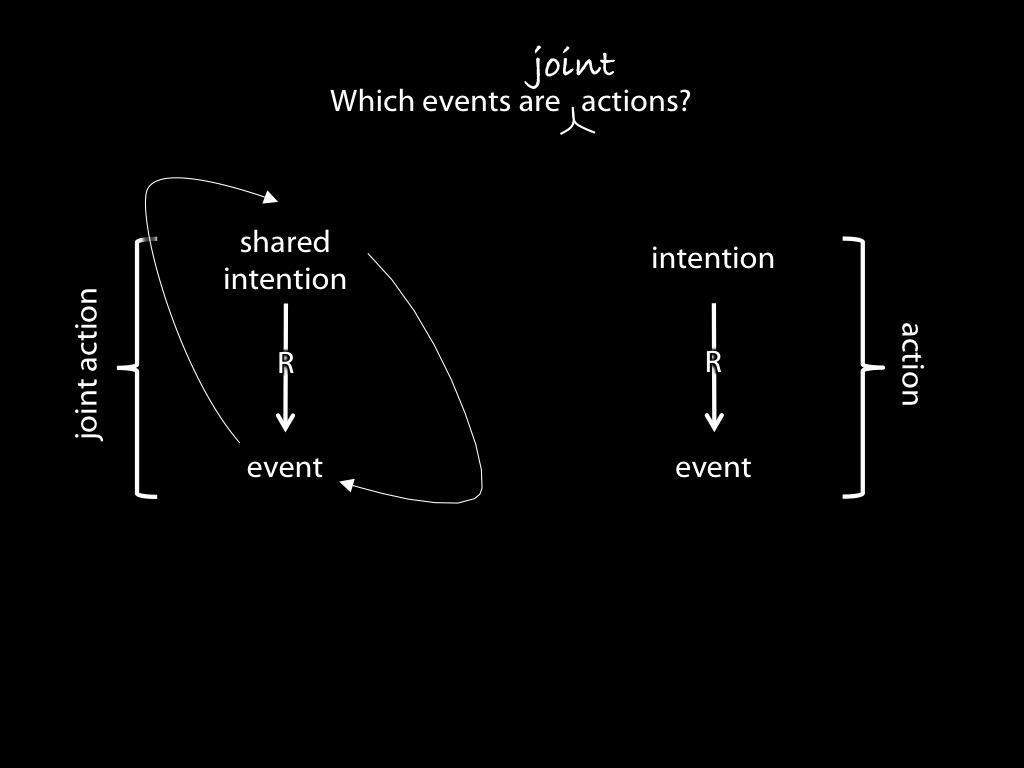

Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Simple View Revised

... and

we engage in parallel planning;

for each of us, the intention that we, you and I, φ together leads to action via our contribution to the parallel planning

(where the intention, the planning and the action are all appropriately related).

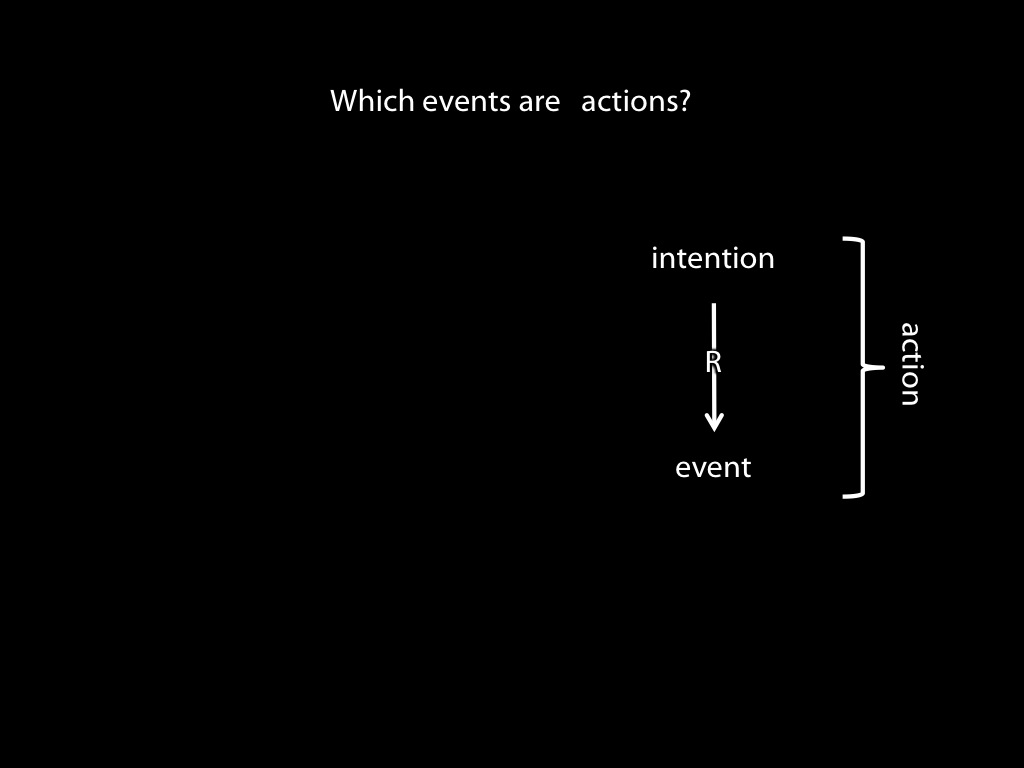

Some intentions specify collective goals.

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

In virtue of what

do very small scale joint actions

have collective goals?

Interagential structures of motor representations.

In virtue of what

are very small scale joint actions

ever trade-off cooperative?

Interagential structures of motor representations.

break

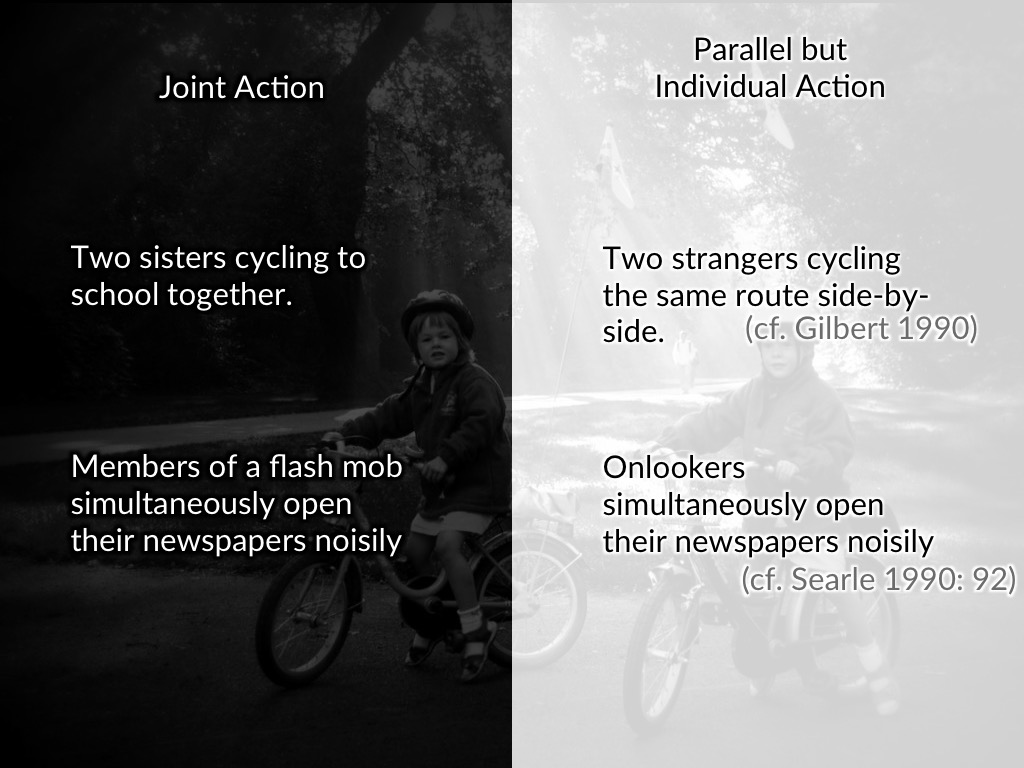

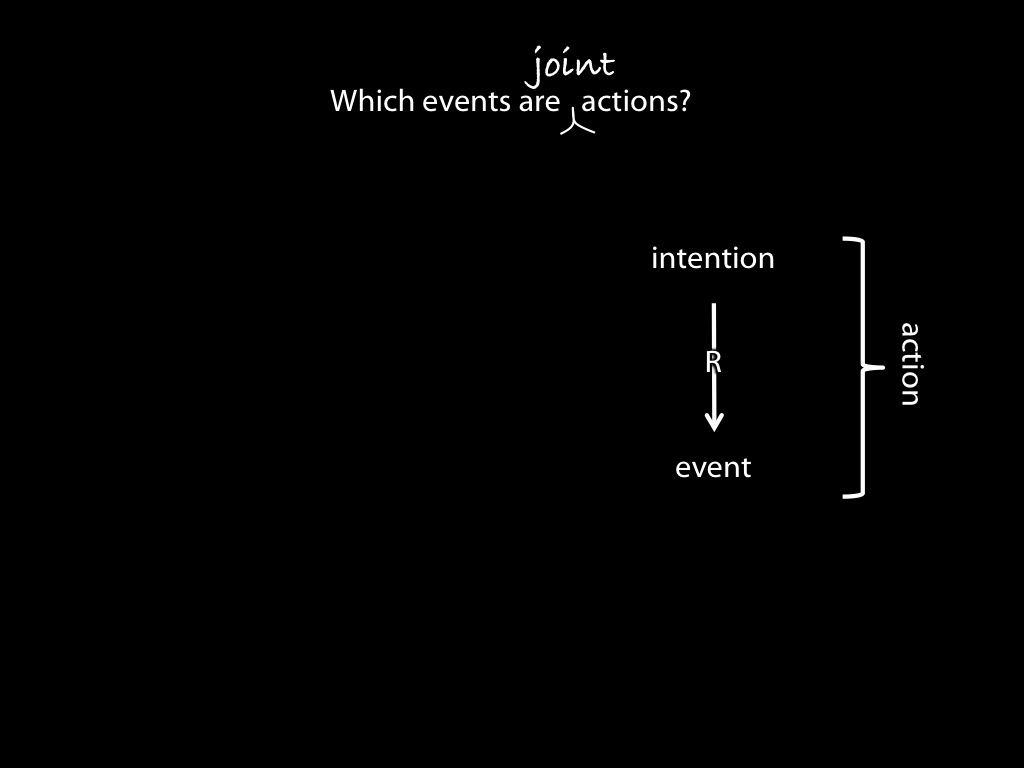

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

Any account of shared agency must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

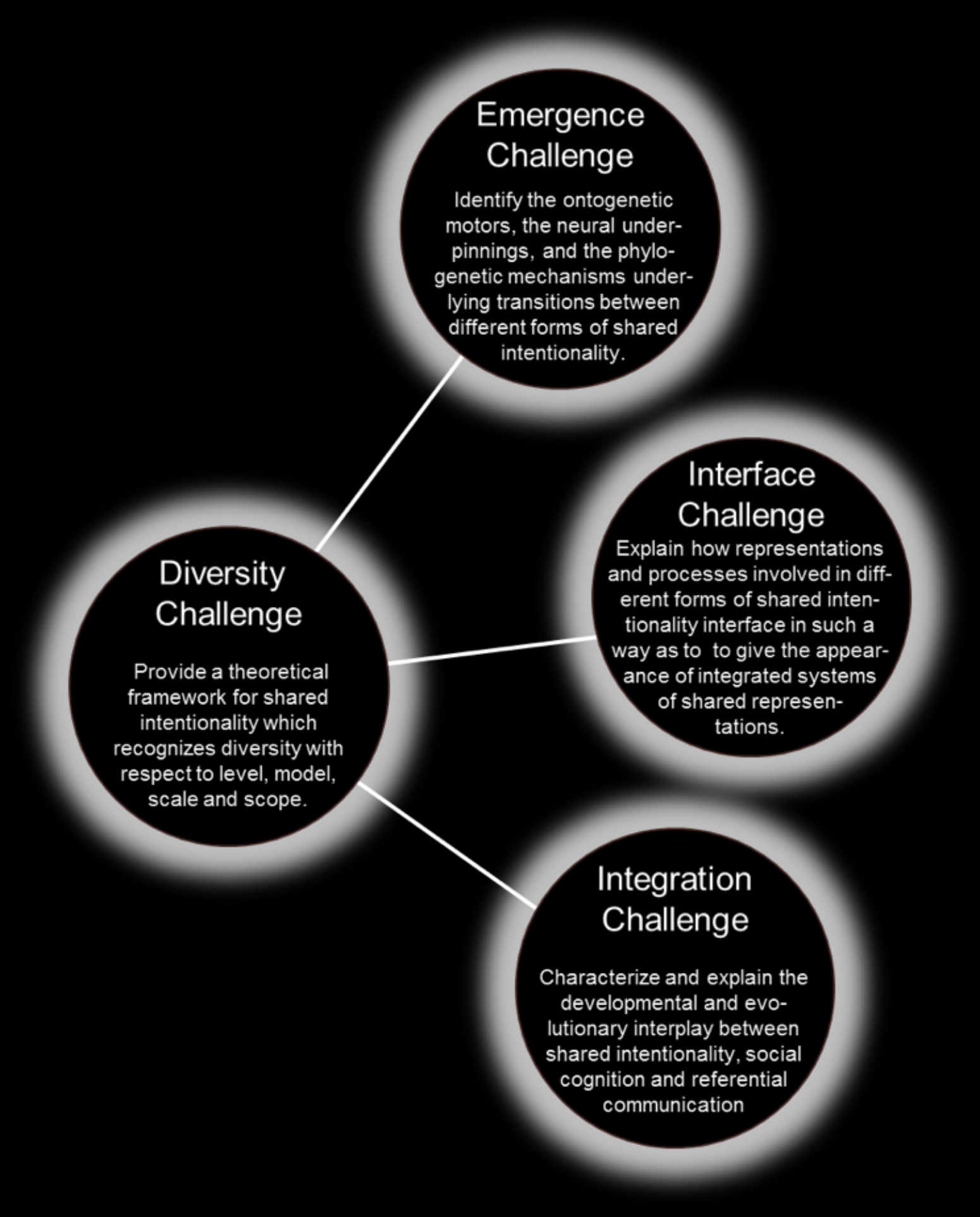

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

shared intention

‘joint activity is explained by such a shared intention; whereas no such explanation is available for the combined activity’ of those acting in parallel but merely individually.

‘This does not, however, get us very far; for we do not yet know what a shared intention is’

Bratman, 2009 p. 152

Challenge: Give an account of shared intention.

aggregate subject

Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Simple View Revised

... and

we engage in parallel planning;

for each of us, the intention that we, you and I, φ together leads to action via our contribution to the parallel planning

(where the intention, the planning and the action are all appropriately related).

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

Any account of shared agency must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

a deeper understanding

Separate

the thing to be explained

from

the thing that explains it.

How to ground a theory of joint action?

Step 1: identify features ...

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- experience

Step 2: ... which generate how questions.

Bratman on strategic equilibrium: This ‘seems not by itself to ensure the kind of sociality we are after [...] a shared activity of the sort we are trying to understand---[...] in the relevant sense, walking together [... There are] important aspects of such shared activities that seem not to be captured [...] our job is to say what those aspects are and how best to understand them’

How to ground a theory of joint action?

Step 1: identify features ...

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- experience

Step 2: ... which generate how questions.

conclusion

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

Rakoczy et al (in progress)

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

Conjecture:

Shared agency begins with primitive forms of acting together.

Interagential structures of motor representation provide a basis for insight.

Ultimately, sophistication hinges on our becoming self-reflective aggregate agents.

Sharing a Smile