Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

\def \ititle {Lecture 01}

\def \isubtitle {Joint Action}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

What did you do today? It is likely that some of your answers to this question refer to things you

did individually and others to things you did jointly with others. In commonsense thinking about

action and intention, the notion that many of the things that matter most in our lives are things

we do with others seems unproblematic.

But theoretically things are rather different.

In developmental, cognitive and philosophical research there is a long tradition of focusing

exclusively on actions with just one agent.

There is no theoretical justification for the focus on just one individual acting alone seems hard

to justify---it simply makes things easier.

But to restrict attention to actions with just one agent seems arbitrary. And, worse, to exclude

many of the things that matter most.

We humans are, after all, one of those species that nurture babies cooperatively.

It’s not just that we care to do things with others:

capacities for joint action are critical for our species’ survival.

We need, therefore, to shift focus from one individual acting along to cases in which

two or more individuals act together.

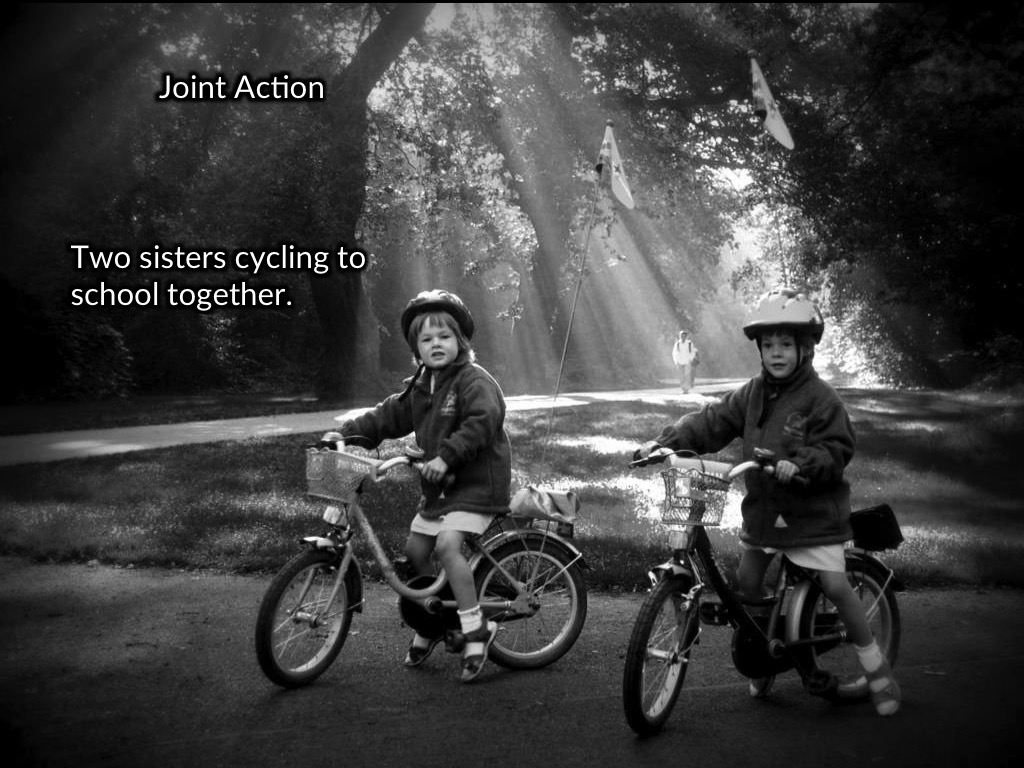

That is, we need to shift from individual to joint action---such as moving a log together, sharing

a smile, or ...

... cycling to school together.

The examples are deceptively simple.

Philosophically, shifting from individual to joint action turns out to be surprisingly tricky.

Our aim in this module is to understand some of the puzzles we face in trying to understand,

at a very basic level, what is involved in joint action. And maybe we will even solve some of them.

\section{The Question}

Introduces the question around which this module is organised.

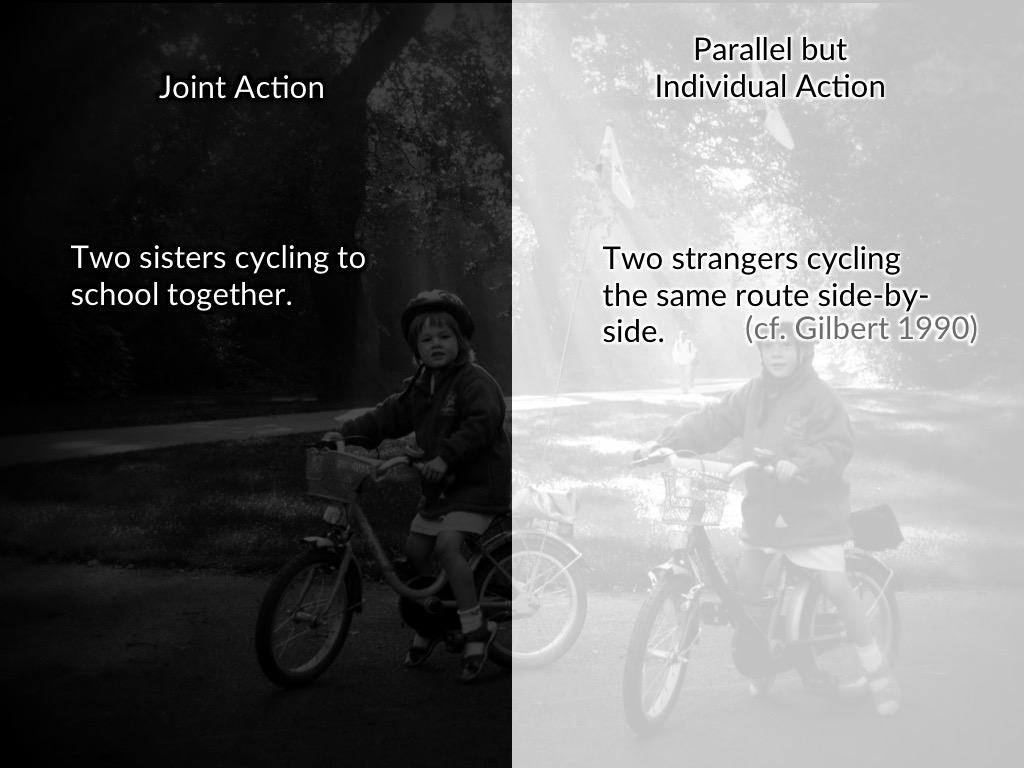

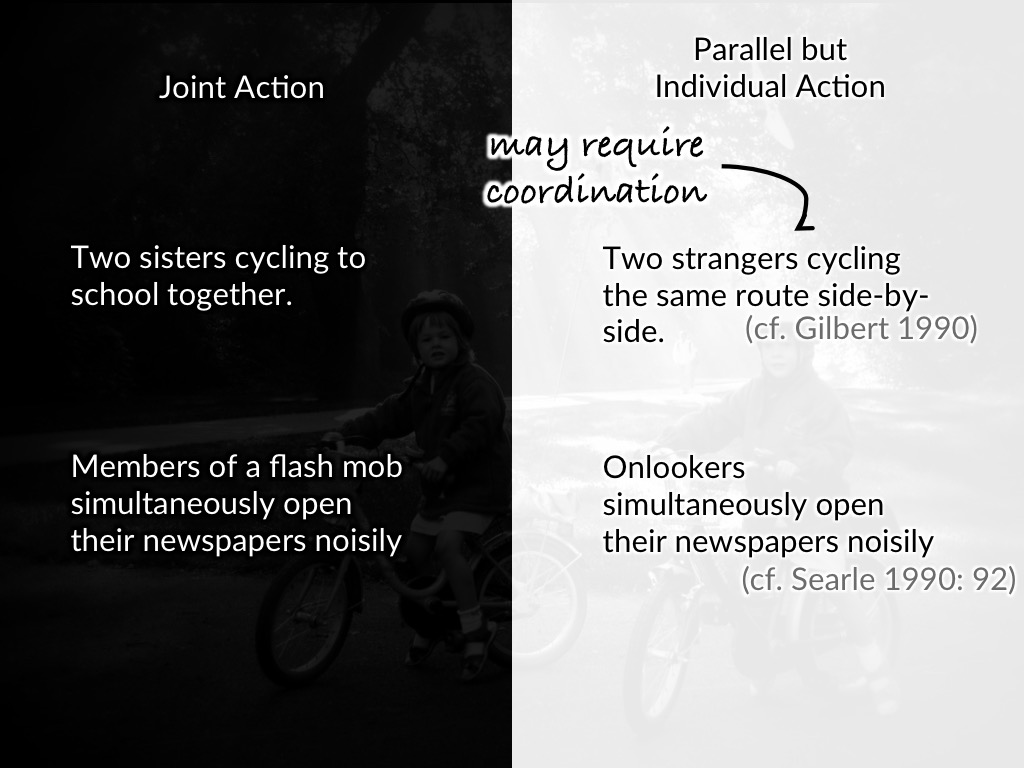

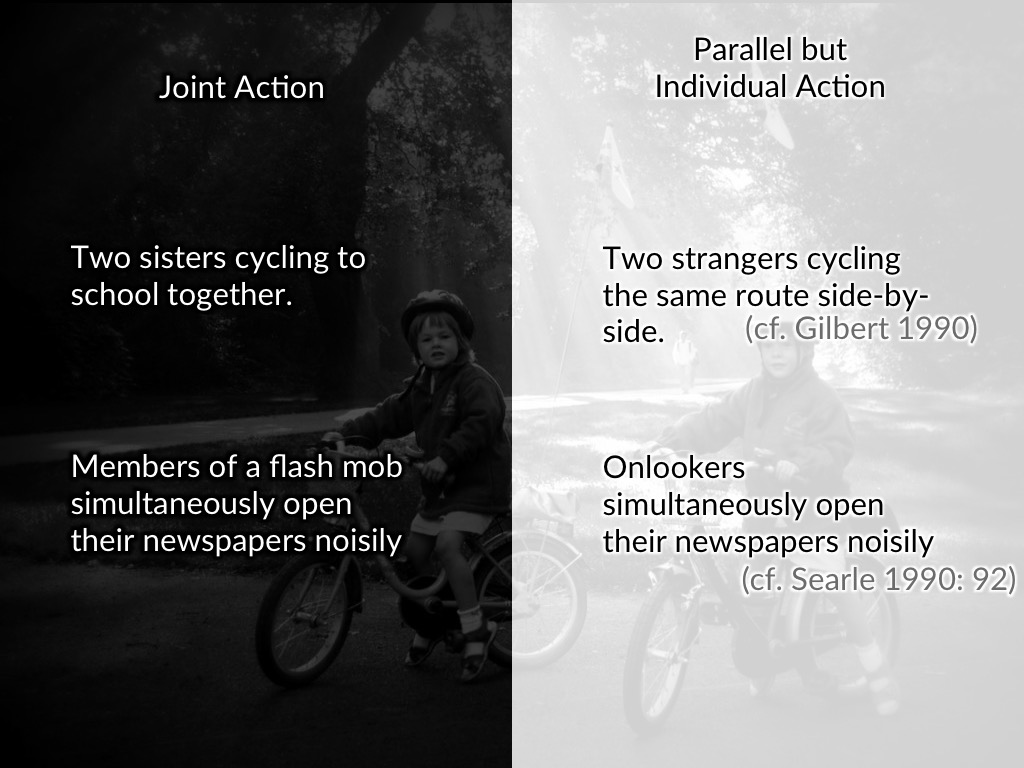

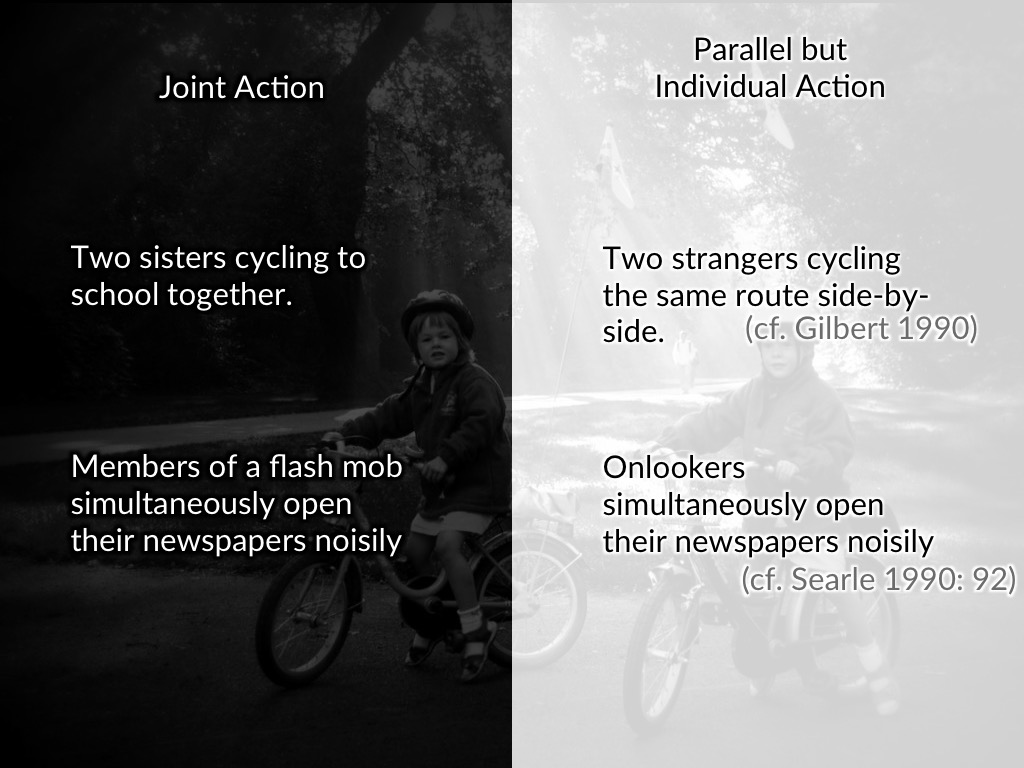

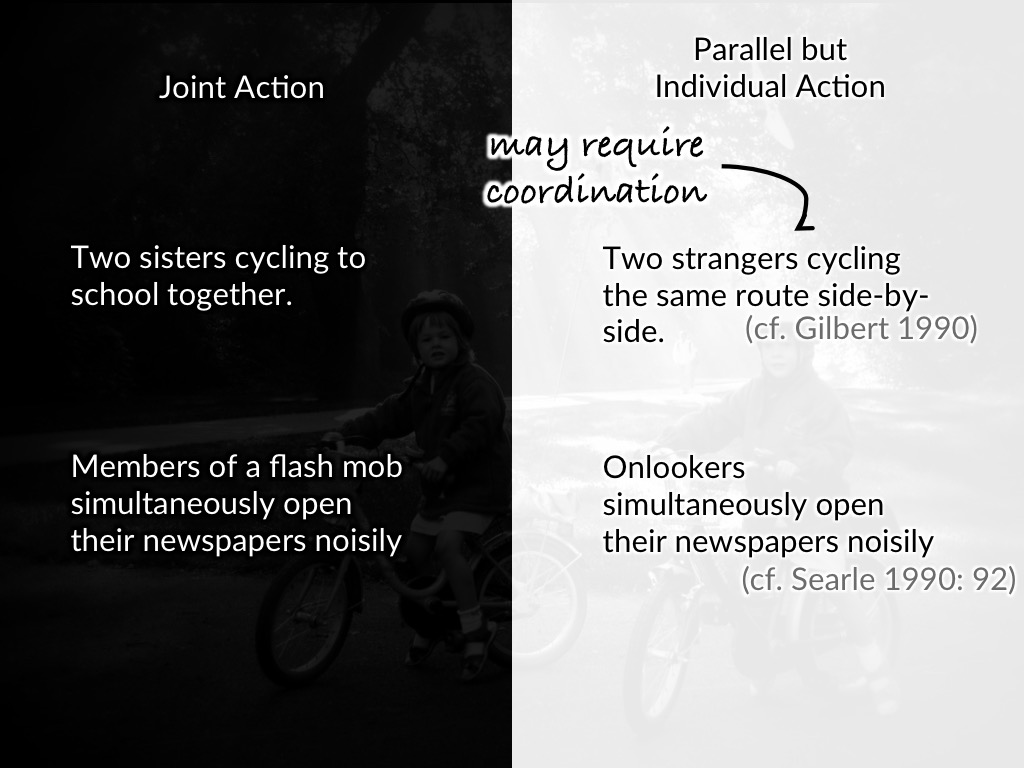

Getting a pre-theoretical handle on joint action is best done by contrasting

joint actions with actions that are merely individual but occur in parallel.

(The method of contrast cases is familiar from Pears (1971), who used

contrast cases to argue that whether something is an ordinary, individual action

depends on its antecedents.)

Let’s start by trying to get a pre-theoretical handle on the notion of joint action.

I’ve already given you some examples, but it’s even better to use contrast cases ...

You have two minutes to think of another pair of examples which contrast joint action

with parallel but merely individual action.

Give another contrast pair.

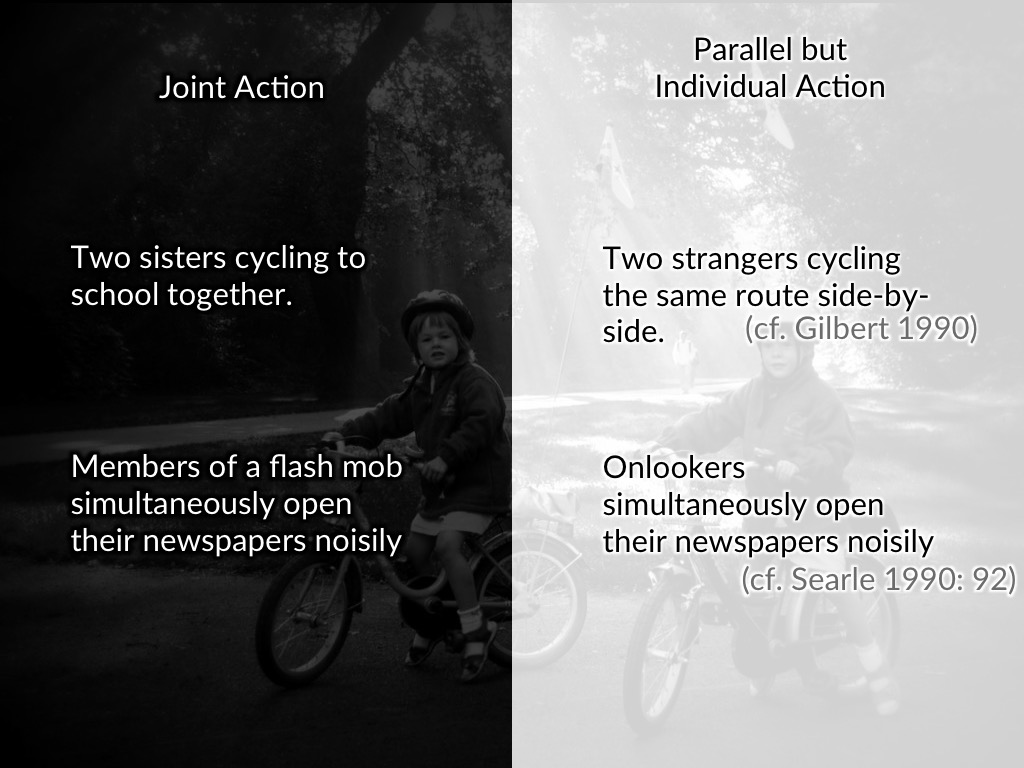

These and other contrasting pairs invite the question, What distinguishes

joint action from parallel but merely individual action?

A natural first thought is that in joint action, our actions are coordinated.

But this turns out not to be a distinguishing feature of joint action because ...

... when two strangers cycle side by side, their actions may need to be highly coordinated

so that they do not crash even if they are merely acting in parallel.

Another idea is that in joint action, our actions have a common effect.

So, for example, when the flash mob open their newspapers, there is a strikingly loud rustle

of paper. None of them individually cause this loud rustle: instead it is a common effect of their

actions.

But consider the actions of the flash mob together with those of the onlookers.

All of these actions have a common effect---the strikingly loud rustle of paper is produced by the

simultaneity of their actions. And this applies to the onlookers who merely happen to open

their newspapers just as the flash mob starts no less than to the members of the flash mob.

So what does distinguish joint action from actions which occur in parallel but are merely individual?

Not coordination, not common effects. So what is it?

[This is just to say that the question, What distinguishes

joint action from parallel but merely individual action? is not straightforward to answer. ]

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

This is the organising question for our project (the project to be investigated in this

series of lectures). Of course there will be lots of further questions, but I like to

have something simple to frame our thinking and this question serves that purpose.

My hope is that by answering this seemingly straightforward question, we will be

in a position to answer the hard question about which forms of shared agency

underpin our social nature.

The first two contrast cases are supposed to show that this question isn’t easy

to answer because the most obvious, simplest things you might appeal to---coordination

and common effects---won’t enable you to draw the distinction.

Aim

An account of joint action must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but

merely individual actions.

This invites us to think in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions.

Of course, there are all kinds of reasons why this might be problematic, and we

will consider many such reasons.

But as I just said, having simple ideas to frame our thinking is good, and that’s why

I take this as my working aim.

(The ultimate aim is a ‘Blueprint for a Social Animal’, but it is difficult to be

precise about what that will involve at this stage.)

So What?

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

A \emph{joint action} is an exercise of shared agency.

Individual vs Aggregate -- both miss shared agency

In philosophy of mind and action, it is normal to focus just on a single individual

who might as well be acting in isolation. But if you think about almost any aspect of

cognition and agency, it is striking that it can’t be fully understood in isolation.

Our capacities for knowledge, emotion and action depend in numerous ways on our

interactions with others.

By contrast with philosophy, many disciplines such as economics and sociology do

treat multiple individuals. But on the whole this involves treating individuals

as indistinguisable from one another.

So once again, on the aggregate perspective, there is no room for shared agency.

There is growing awareness in cognitive science and philosophy that in missing

shared agency we may be missing something that shapes our lives and explains

much about why we humans are the way we are.

Excitingly, new techniques and technologies to investigate shared agency are

being developed too.

At the same time there is an amazing degree of uncertainty and even confusion

among philosophers and theoretically-minded scientists.

It’s not just that there are different theories of shared agency; there is

fundamental disagreement about what sort of conceptual and ontological resources

are needed, and about the questions such a theory should answer.

As you’ll see, there are even two completely unconnected articles on this topic

in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

So we face lots of challenges ...

So here you have the question for this course, our aim and the reason it matters.

lectures

lectures are at this time every week

web

there is a web page where you can find slides and handouts from lectures.

assessment = essays

The authoritative source for the deadlines is your undergraduate handbook.

In case of doubt, please check there.

(titles on the web under ‘course materials’)

reading week

there are no lectures or seminars in reading week (week 6)

seminars

Seminars start next week and run every week except reading week.

seminar groups

Sign up on tabula, as usual.

seminar tasks

--- yyrama ...

first seminar tasks

https://yyrama.butterfill.com/course/view/JointAction

Short (<501 words) writing assignment.

What is the Simple View? First carefully introduce the question about joint action to which the Simple View is supposed to be an answer. Then introduce and evaluate an objection to it. ...

Also: provide a peer review of another student’s work.

But what is the Simple View? I’m so glad you asked ...

\section{The Simple View}

The Simple View is an answer to the question,

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

According to the Simple View, two or more agents perform an intentional joint action exactly when

there is an act-type, φ, such that

each of several agents intends that they, these agents, φ together and their intentions are

appropriately related to their actions.

Recall our question, What distinguishes joint action from parallel but merely individual action?

As we saw, it isn’t just that joint actions are coordinated, nor just that they have common effects.

Maybe we need to think in not in terms of the actions but in terms of the intentions behind them?.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

What distinguishes

an ordinary, individual action from a mere happening?

We can understand this idea by comparison with a claim about

ordinary, individual action.

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

For example, suppose the coffee in cup in your hand ends up all over my face.

This event might involve an action on your part, or it might be a mere happening.

What distinguishes the two?

Your intention that you throw the coffee at me.

One quite standard idea is that it is intention.

Where the event is an action, you must have an intention to throw coffee in my face

and this intention must be appropriately related to your action.

By contrast, where there is no such intention the event is merely an accident.

What distinguishes

genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Our intentions that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

\emph{The Simple View}

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Explain: ‘I wish I had done that’.

We are no longer talking about joint action generally, only about intentional joint action.

Compare individual action: much individual action is arguably purposive but not

intentional. Similarly, we might think that there are non-intentional but purposive joint

actions.

A further problem concerns the link between intentional joint action and intention.

Consider individual action. Bratman has good arguments for holding that actions can

be intentional under a description even when no intention specifies that description;

and he also holds that agents incapable of intending may nevertheless perform intentional

actions.

So it is conceivable that not all intentional joint action will involve intention.

In that case, the Simple View may not even be a fully general account of intentional

joint action.

I’m not going to pursue these issues yet, but we will come back to them.

For now I just want to note that, for all its simplicity, the Simple View raises some

tricky questions.

For now I am treating the Simple View as offering necessary and sufficient conditions

for intentional joint action, because I want to start with an ambitious claim.

But reflecion on the relation between intention and intentional action may force us to back

down later.

Explain: deviant causal chains.

The Circularity Objection

\section{The Circularity Objection}

According to the Simple View, what distinguishes a joint action from parallel but merely individual

actions are the agents’ intentions that they, these agents, act together.

But does invoking acting together make this idea circular?

Recall that the Simple View is an answer to our question,

What distinguishes joint action from parallel but merely individual action?

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

Consider a first objection to the Simple View, a threat of circularity.

You might imagine that appealing to togetherness in the specifying the content

of the intention introduces circularity.

\textbf{Doesn’t doing something together involve exercising shared agency?

And if it does, aren’t we explaining shared agency by appeal to intentions

to exercise shared agency?}

Schweikard and Schmid (2013) offer one formulation of the circularity objection a challenge:

‘[H]ow can an individual refer to a joint activity without the jointness

[...] already being in place?’ (Schweikard and Schmid, 2013)

To see how this objection arises, consider two possible intentions:

Contrast:

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school apart.

Suppose we each had and acted on the latter intention (that we, you and I, cycle to school apart).

Then our actions would not be joint actions.

So apparently, appealing to togetherness is essential.

But doesn’t invoking the togetherness of our this mean assuming the very thing we were

supposed to be characterising---namely joint action?

acting together vs exercising shared agency

Many of the things we do together involve exercising shared agency. We play duets,

move pianos together and drink toasts together.

But we also do things together without exercising shared agency.

We fill rooms with noise together, damage

furniture together and spill drinks together, for example.

Who woke the baby?

It wasn’t me alone, and it wasn’t you alone either---neither of us was

laughing quite loudly enough to do so alone.

Rather, waking the baby was something we did together. But in waking the baby we were

not exercising shared agency.

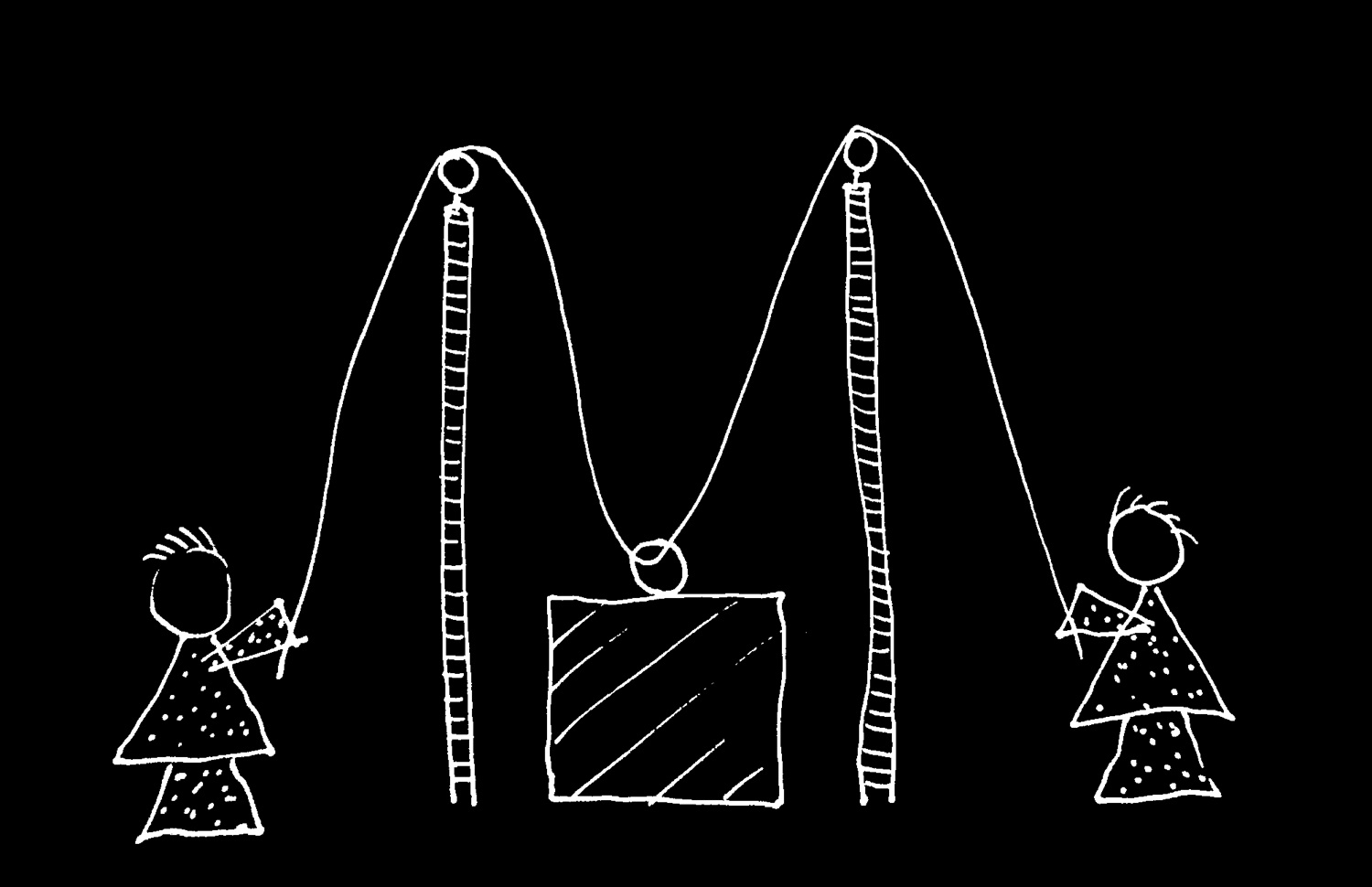

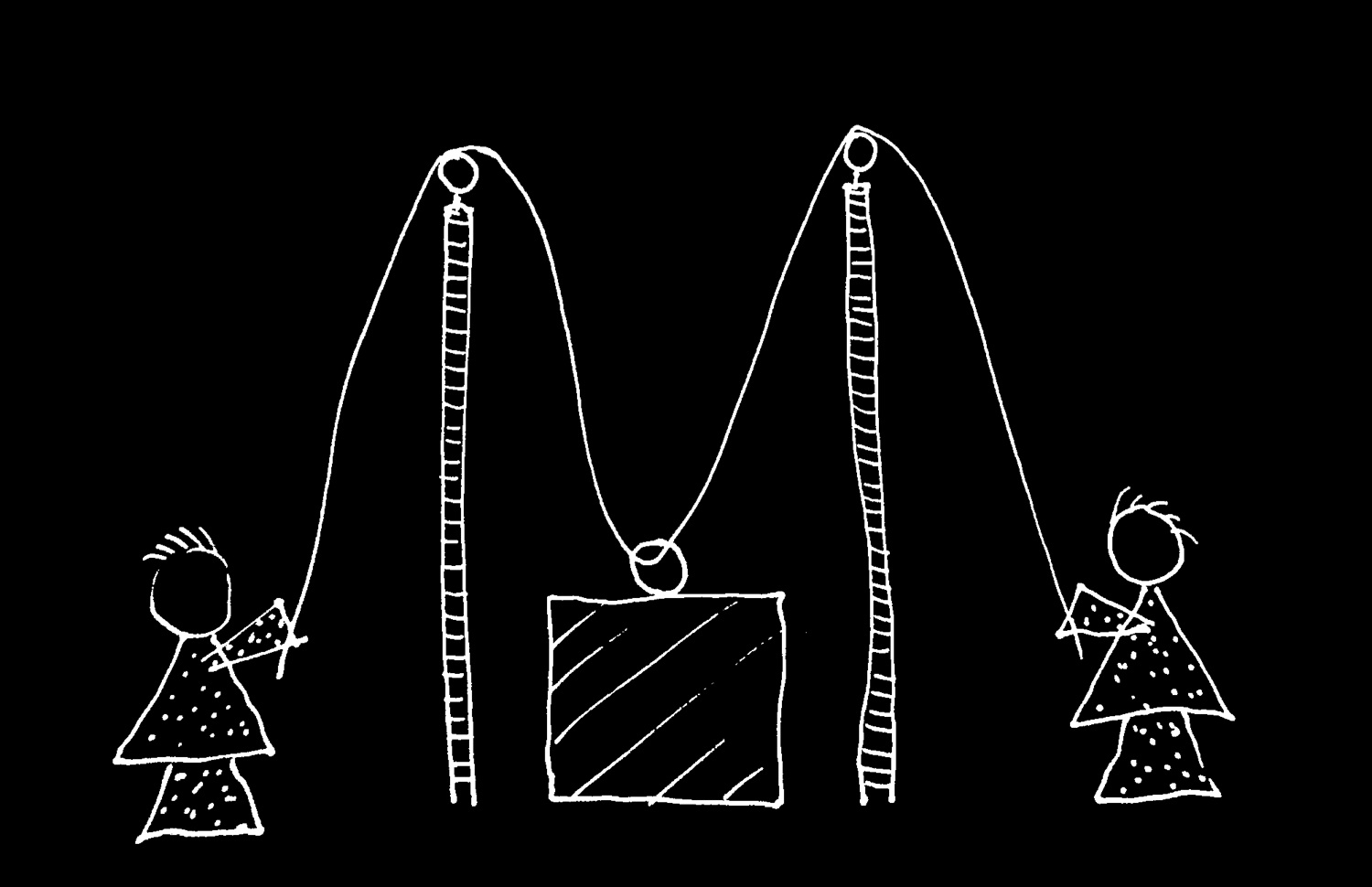

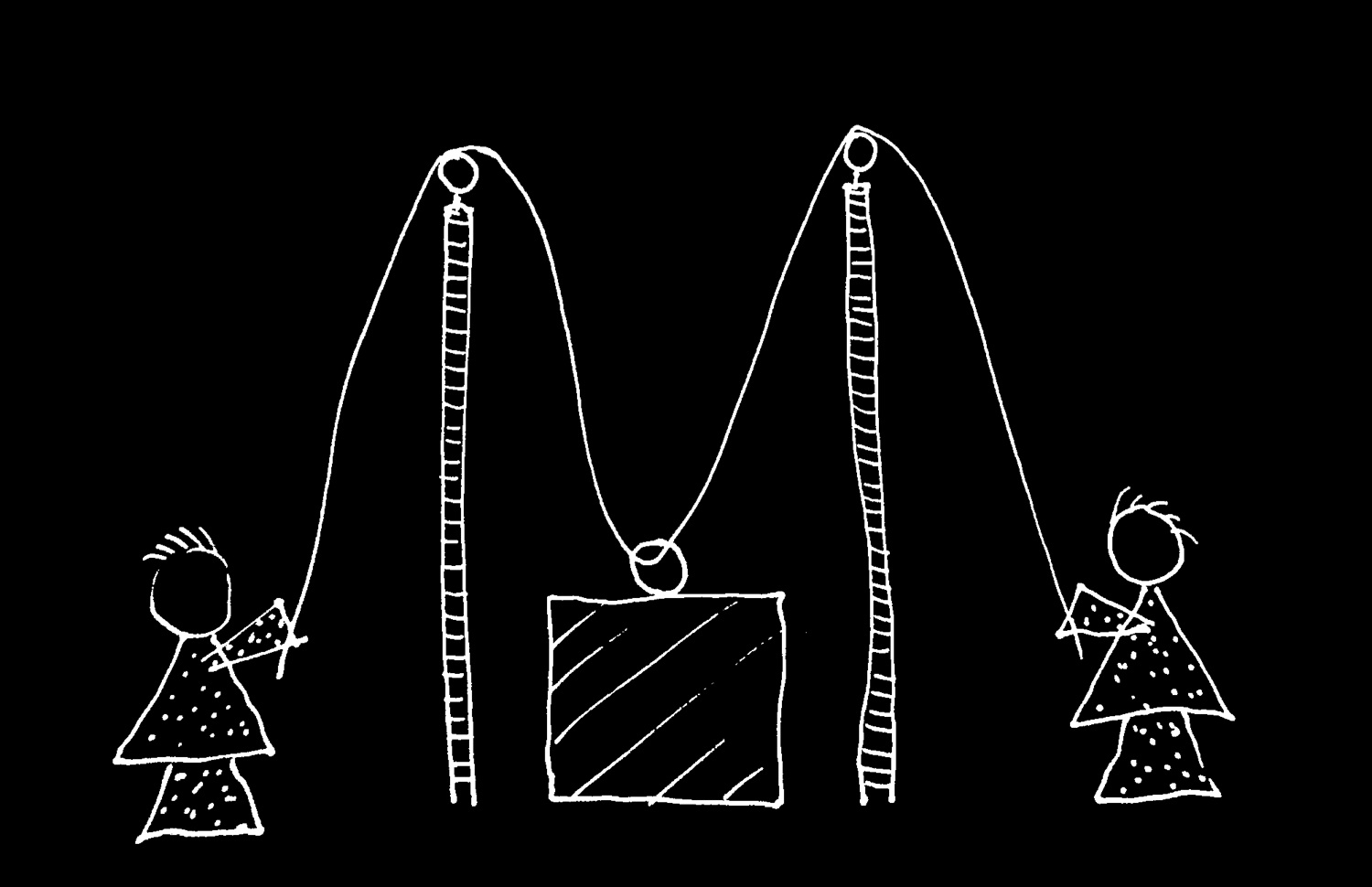

Two ropes hanging over either side of a high wall are connected to a heavy block

via a system of pulleys. Ayesha and Beatrice pull the ropes simultaneously,

causing the heavy block to rise as a common effect of their actions. Each

individually intends to raise the block. Each can see the block’s rise but,

because of the high walls, neither of them is aware of the other, nor

even that anything other than her own action is necessary for the block

to rise.

In fact neither is aware that they are acting with another individual.

Each believes, falsely, that there is a simple motor on the other end of the

pulley, and that when the rope tenses the motor will turn.

Consider two questions ...

Are Ayesha and Beatrice

acting together?

Is Ayesha and Beatrice’s

lifting the block together

a joint action?

This question is less straightforward to answer than the first two.

There actions are coordinated and have a common effect,

but we saw earlier that this is true of many things which merely involve

people acting in parallel rather than exercising shared agency.

I think most people working in this area would say that

Ayesha and Beatrice’s lifting the block together is not a joint action.

But in this area there is a real danger that we are just trading intuitions.

So let’s see if we can find a basis for deciding whether this is a joint action.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

Recall that Schweikard and Schmid (2013) offer one formulation of the circularity objection a challenge:

‘[H]ow can an individual refer to a joint activity without the jointness

[...] already being in place?’ (Schweikard and Schmid, 2013)

How should we respond?

I think: (a) not everything we do together is a joint action (e.g. waking the baby);

(b) in each intending that we, you and I, cycle to school together,

we are referring to what is in fact a joint activity but we are not referring to it \emph{as} a

joint activity; instead, we are referring to it merely as something we do together.

For comparison, suppose that we intend that these papers serve as a means of exchange

between us and a store of value. This intention is, let’s say, what makes it the case

that these papers are money. So there’s nothing problematic with referring to money

without the money already existing (or ‘being in place’).

terminology:

shared agency

joint action

A \emph{joint action} is an exercise of shared agency.

Joint actions include very small scale interactions such as hugging or sharing a

smile, larger small group efforts like dancing together, going for a walk

or paining a house, and also epsiodes involving multiple agents and long periods

of time like buidling a city or founding a democracy.

‘collective’ action / agency

People sometimes use ‘collective’ rather than ‘joint’ or ‘shared’. These terms

tend to be used interchangeably rather than to mark significant differences.

(Although Tomasello has made a reasonable suggestion.)

Terminology is a mess; as usual.

---

acting together

I’ve just suggested that that not all cases of acting together involve shared agency.

The Circularity Objection Again

\section{The Circularity Objection Again}

According to the Circularity Objection,

the Simple View fails to adequately answer to the question,

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Here we consider a deeper reply to the Circularity Objection.

‘Examples of what I shall refer to ... as “acting together” include dancing together, building a house together, and marching together against the enemy, where these are construed as something other than a matter of doing the same thing concurrently and in the same place’

Gilbert 2013, p. 23

\citep[p.~23]{gilbert:2014_book}

Say hello to the first of several major figures on joint action, Margaret Gilbert.

Note the contrast she wants to draw between acting togther and several people

‘doing the same thing concurrently and in the same place’.

This seems reasonable.

Now for our purposes Gilbert is relevant because she takes acting together to be

the same thing as joint action. In that case, the Simple View would clearly be

circular. (You can’t appeal to acting together in explaining what joint action is

if acting together *is* joint action.)

Let me emphasise this point with a different quote from Gilbert.

‘The key question in the philosophy of collective action is simply ... under what conditions are two or more people doing something together?’

\citep[p.\ 67]{Gilbert:2010fk}

Gilbert 2010, p. 67

If this is correct, the Circularity Objection would appear inescapable.

Certainly the reply I’ve just offered to it would be inadequate.

We are going to explore Gilbert’s views in some detail later in the course, but let

us have a quick peek at what she thinks is involved in acting together ...

Here is Gilbert’s own statement of her view.

‘two or more people are acting together if [and only if] they are jointly committed to espousing as a body a certain goal, and each one is acting in a way appropriate to the achievement of that goal, where each one is doing this in light of the fact that he or she is subject to a joint commitment to espouse the goal in question as a body.’

Gilbert 2013, p. 34

\citep[p.~34]{gilbert:2014_book}

There is a lot going on here but I want to zoom in on just one feature for now,

the joint committment.

Joint committment is Gilbert's central notion.

Start with individual committment (which Gilbert calls ‘personal commitment’).

You can make an individual committment to me that you will write an essay,

and I can make an individual committment to you that I will mark it.

In this case the committment entails certain obligations and perhaps rights.

Gilbert’s idea is that several people can also become collectively committed,

in which case they have a joint committment which entails collective obligations.

So the idea is that a joint commitment

is something irreducibly collective.

This is an interesting idea which will become clearer later.

(We need to think more carefully about the basic individual/collective contrast.)

But for now I just want to note that Gilbert thinks along these lines ...

- Every event of acting together is a joint action.

- Every joint action constitutively involves joint committment.

If Gilbert is right the worry about the circularity of the Simple View is

clearly justified. But is Gilbert right?

Let me go back to Ayesha and Beatrice lifting the block.

Consider two questions ...

Are Ayesha and Beatrice acting together?

Do Ayesha and Beatrice have a joint commitment?

On Gilbert’s view, you cannot say yes to one and no to the other.

I think you can, of course.

But at this point we are just in danger of trading intuitions.

And if I’m wrong, the Circularity Objection would appear to be correct.

Can we find an argument here?

collective vs distributive

Here are two sentences:

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

The first sentence is naturally read *distributively*; that is, as specifying something

that each drop did individually. Perhaps first drop one fell, then another fell.

But the second sentence is naturally read *collectively*.

No one drop soaked Zach’s trousers; rather the soaking was something that the drops

accomplised together.

If the sentence is true on this reading, the tiny drops' soaking Zach’s trousers is not

a matter of each drop soaking Zach’s trousers.

[*Might need more examples. Bad pint?

Ask them to think of an example?]

Here is a second example contrasting distributive vs collective interpretations.

Consider the sentence ‘The ants carried tiny stones’. This is naturally interpreted as

implying only that each ant carried a tiny stone, which is a distributive interpretation.

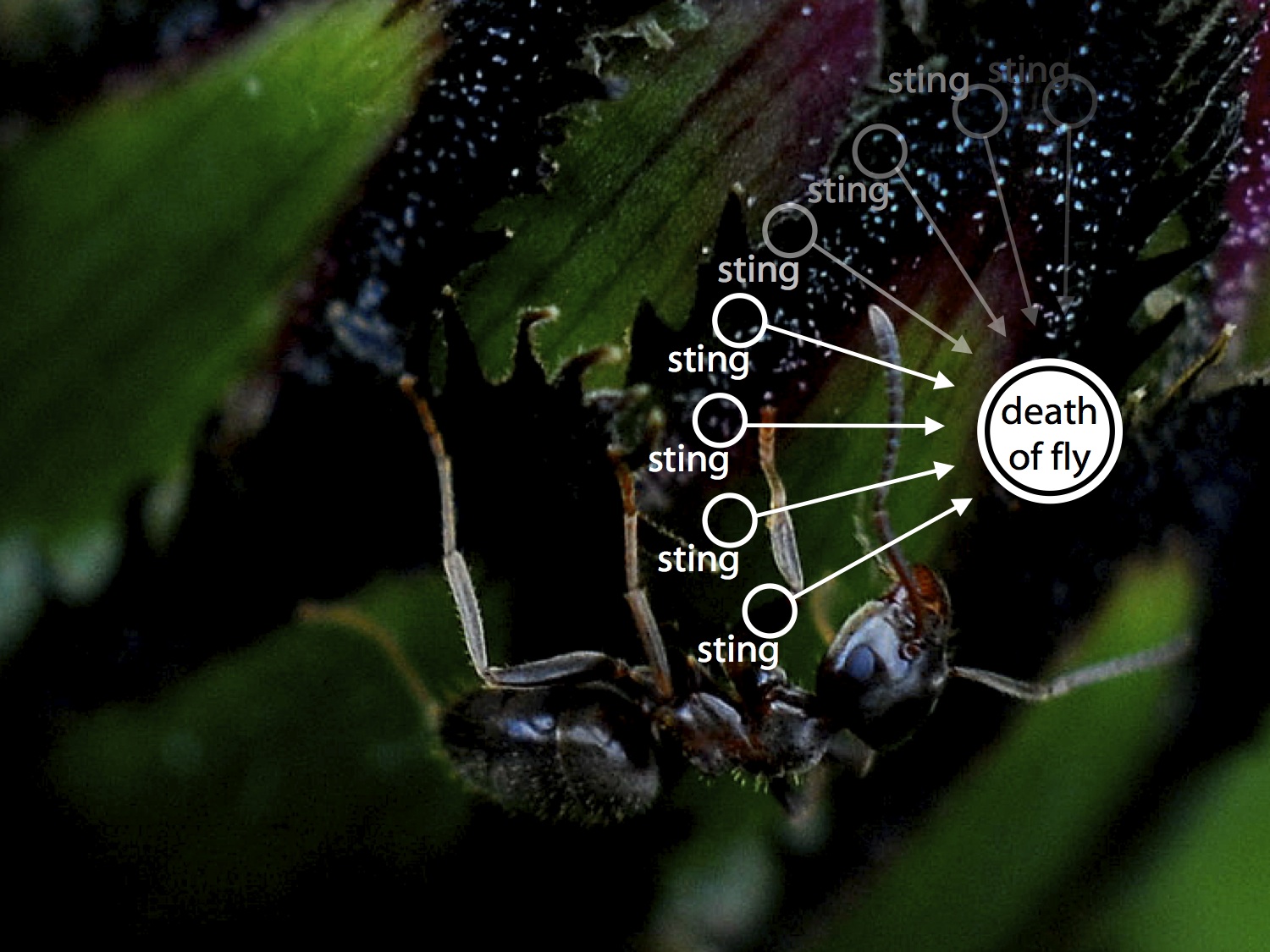

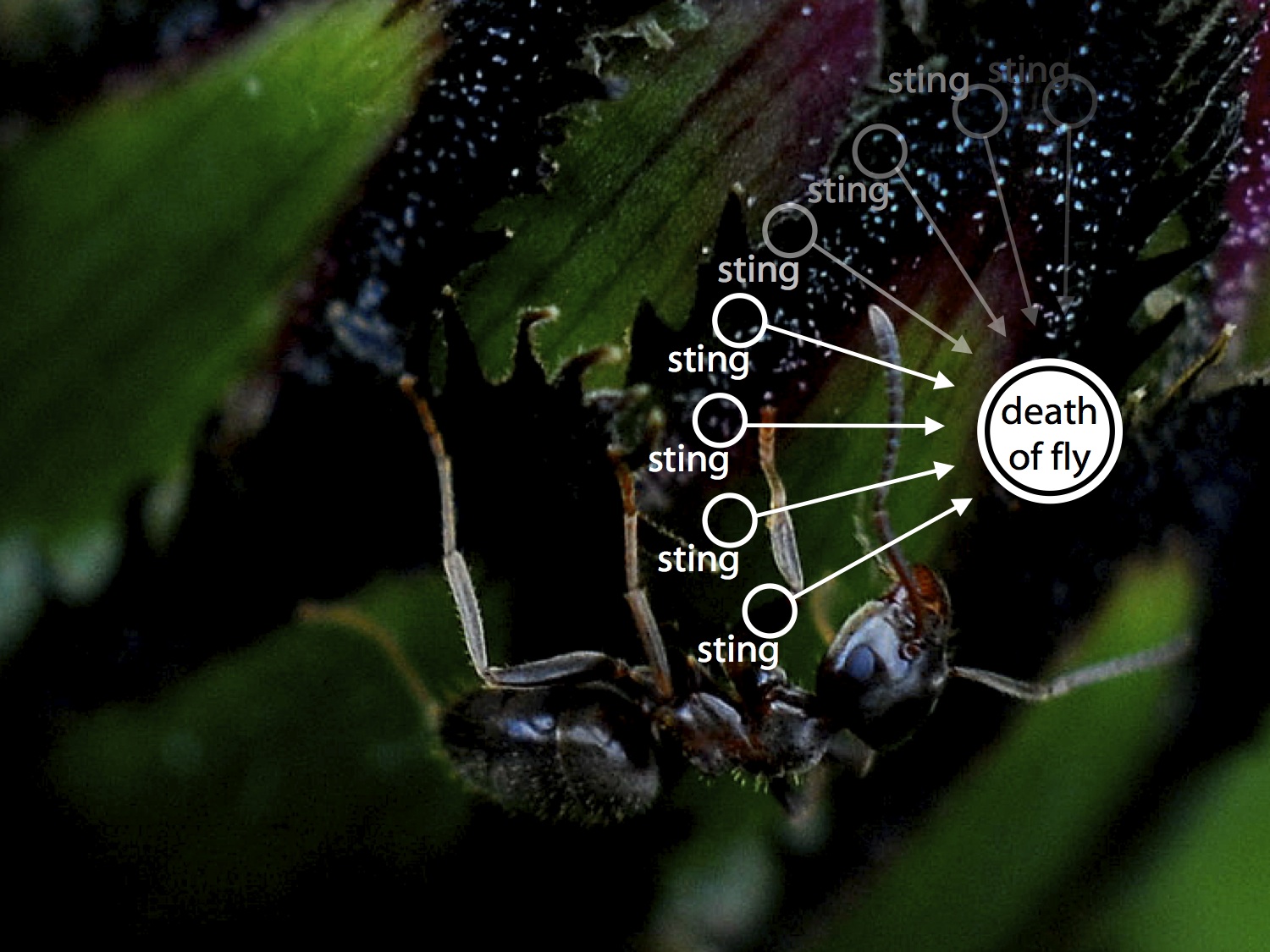

By contrast, consider this ...

Some ants harvest plant hair and fungus in order to build traps to capture large insects;

once captured, many worker ants sting the large insects, transport them and carve them up

\citep{Dejean:2005vb}.

There’s a lot you might extract from this behaviour (and we will return to the ants later),

but for now just focus on the killing.

Each ant stings the large insect they have captured, where none of the stings are

individually fatal although together they are deadly.

So when I tell you that the ants killed the large insect, this should be interpreted

collectively. That is, it is not a matter of each ant killing the large insect;

rather killing is collectively predicated of the ants.

You have two minutes to think of two sentences which, like mine,

illustrate the contrast between collective and distributive.

Give another

collective-distributive

contrast pair.

Here are is my first example of the distinction between distributive and collective interpretations again ...

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

Now consider an example involving actions and their outcomes:

Their thoughtless actions soaked Zach’s trousers. [causal]

- ambiguous (really!)

This sentence can be read in two ways, distributively or collectively.

We can imagine that we are talking about a sequence of actions done

over a period of time, each of which soaked Zach’s trousers.

In this case the outcome, soaking Zach’s trousers, is an outcome of each action.

Alternatively we can imagine several actions which have this outcome collectively---as in

our illustration where Ayesha holds a glass while Beatrice pours.

In this case the outcome, soaking Zach’s trousers, is not necessarily an outcome of any of the

individual actions but it is an outcome of all of them taken together.

That is, it is a collective outcome.

(Here I'm ignoring complications associated with the possibility that some

of the actions collectively soaked Zach’s trousers while others did so distributively.)

Note that there is a genuine ambiguity here.

To see this, ask yourself how many times Zach’s trousers were soaked.

On the distributive reading they were soaked at least as many times as there are actions.

On the collective reading they were not necessarily soaked more than once.

(On the distributive reading there are several outcomes of the same type and each

action has a different token outcome of this type; on the collective reading there is a single token

outcome which is the outcome of two or more actions.)

Claim:

When collective, they act together.

Recall Gilbert’s view ...

Gilbert:

- Every event of acting together is a joint action.

- Every joint action constitutively involves joint committment.

Compare these three sentences ...

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers together.

The three legs of the tripod support the camera together.

Ayesha and Beatrice lifted the block together.

I want to suggest that reflection on these allows us to distinguish

merely acting together from performing a joint action. Why? ...

- In each case there is a collective interpretation.

- The collective interpretation is what makes ‘together’ appropriate.

- It is the same sense of ‘together’ in each case.

- (1) and (2) are not joint actions (nor actions).

- So ‘together’ does not entail joint action.

...

acting together doesn’t entail joint action

So I disagree with Gilbert that

‘The key question in the philosophy of collective action is simply ... under what conditions are two or more people doing something together?’

\citep[p.\ 67]{Gilbert:2010fk}

Gilbert 2010, p. 67

This turns out to be a significant problem for Gilbert, who needs to separate her

characterisation of the phenomenon to be explained from the theory that explains it.

In saying this I’m broadly in agreement with Ludwig ...

‘any random group of agents is a group that does something together’

\citep[p.~128]{ludwig:2014_ontology}

Ludwig (2014, p. 128)

The important point here is that acting together is very pervasive and doesn’t require intention

or awareness that we are doing it.

Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

I've been explaining the threat of circularity arising from the fact that the Simple View

involves appeal to ‘acting together’.

The threat was that all events in which we act together are joint actions and so the

Simple View would be explaining joint action by appeal to joint action.

Support from this view comes from Gilbert, who does think that

all events in which we act together are joint actions.

However reflection on the distinction between distributive and collective

interpretations of sentences, inclduing sentences that are not about action at all,

suggested that acting together can occur without there being a joint action.

As things stand, then, we do not yet have a reason to reject the Simple View.

Walking Together in the Mafia Sense

\section{Walking Together in the Mafia Sense}

Does Bratman’s ‘mafia case’ provide a reason to reject the Simple View?

Bratman offers a counterexample to something related to the Simple View \citep[see][]{Bratman:1992mi,bratman:2014_book}.

Suppose that you and I each intend that we, you and I, go to New York together.

But your plan is to point a gun at me and bundle me into the boot (or trunk) of your

car.

Then you intend that we go to New York together, but in a way that doesn't

depend on my intentions. As you see things, I'm going to New York with you whether

I like it or not. Does this provide the basis for an objection to the Simple View?

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Here’s the simple view again. My aim now is to present the most convincing objection

to it that I can.

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

Michael Bratman offers a counterexample to something related to the Simple View.

Suppose that you and I each intend that we, you and I, go to New York together.

But your plan is to point a gun at me and bundle me into the boot (or trunk) of your

car.

Then you intend that we go to New York together, but in a way that doesn't

depend on my intentions. As you see things, I'm going to New York with you whether

I like it or not. This doesn't seem like the basis for shared agency.

After all, your plan involves me being abducted.

But it is still a case in which we each intend that we go to New York together and we do.

So, apparently, the conditions of the Simple View are met (or almost met) and yet there is

no shared agency.

1. I intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

2. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

3. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together by way of you forcing me into the back of my car.

We’re considering that Bratman’s ‘mafia case’ provides a counterexample to

the Simple View. But does it really?

The mafia case fails as a counterexample to the Simple View because if you go through

with your plan, my actions won’t be appropriately related to my intention.

And, on the other hand, if you don’t go through with your plan, that it is at best

unclear that your having had that plan matters for whether we have shared agency.

I suggest that what is wrong in the Mafia Case is not that the agent’s need further

intentions, but just that if their intentions don’t connect to their actions in the

right way then there won’t be intentional joint action.

But the mafia case fails as a counterexample to the Simple View because if you go through

with your plan, my actions won’t be appropriately related to my intention.

And, on the other hand, if you don’t go through with your plan, that it is at best

unclear that your having had that plan matters for whether we exercise shared agency.

Bratman uses the Mafia case to motivate adding further intentions to

those specified by the Simple View.

But I suggest that an alternative response to the Mafia case is no less adequate

and simpler: what is wrong in the Mafia Case is not that the agents need further

intentions, but just that, if they act as they intend, their intentions won’t

all be appropriately related to their actions.

So Bratman’s ‘mafia case’ is not a counterexample to the Simple View.

I note that Bratman is clearly aiming to identify intentions whose fulfilment

requires shared agency. But I don’t think this is necessary.

It seems to me that what matters is that the Simple View as a whole

distingiushes shared agency from parallel but merely individual agency,

not that it does so by way of fulfilment conditions of intentions.

Rather than continuing to discuss whether the Mafia case really motivates rejecting

the Simple View, let me consider other ways to generate what seem to be more

plausible candidates for counterexamples to the Simple View ...

Objectives for this lecture:

- understand questions about shared agency

- can use the method of contrast cases

- familiar with the Simple View

- understand distributive and collective interpretations of sentences

- can critically assess objections to the Simple View