Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Davidson, 1971 p. 43

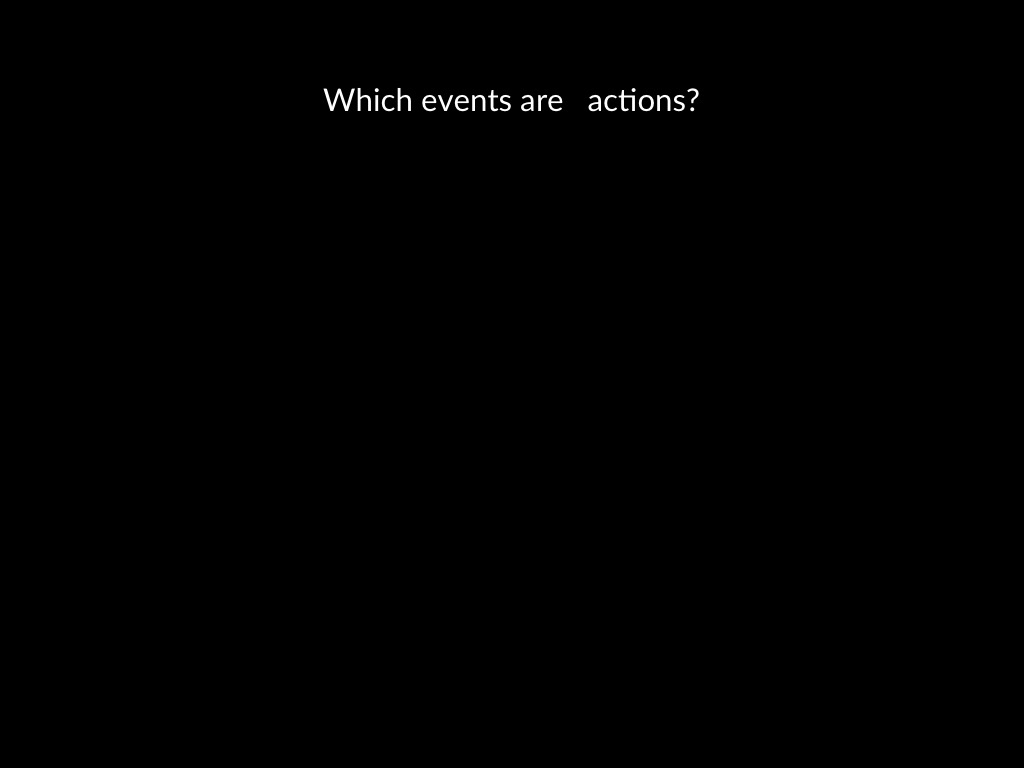

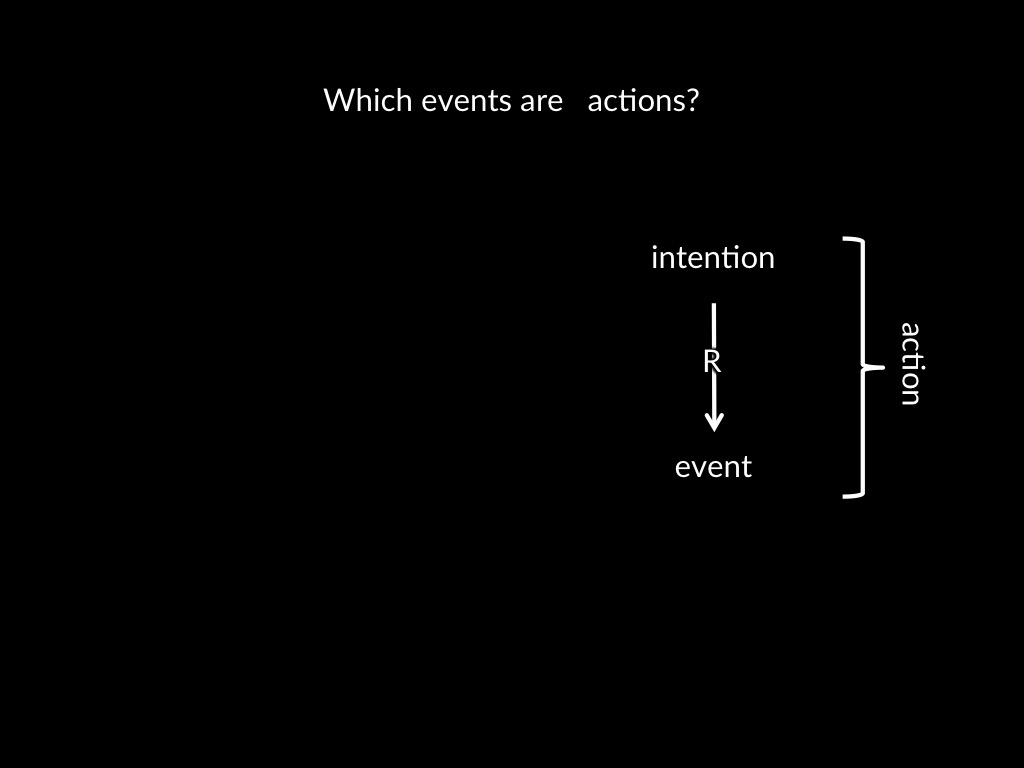

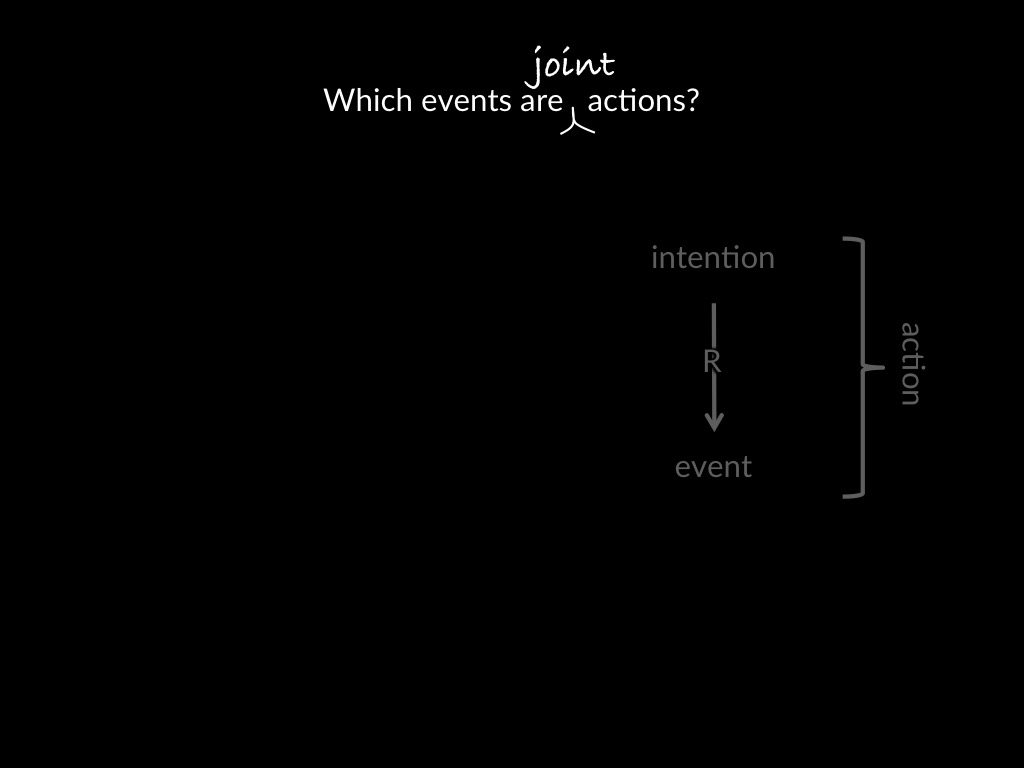

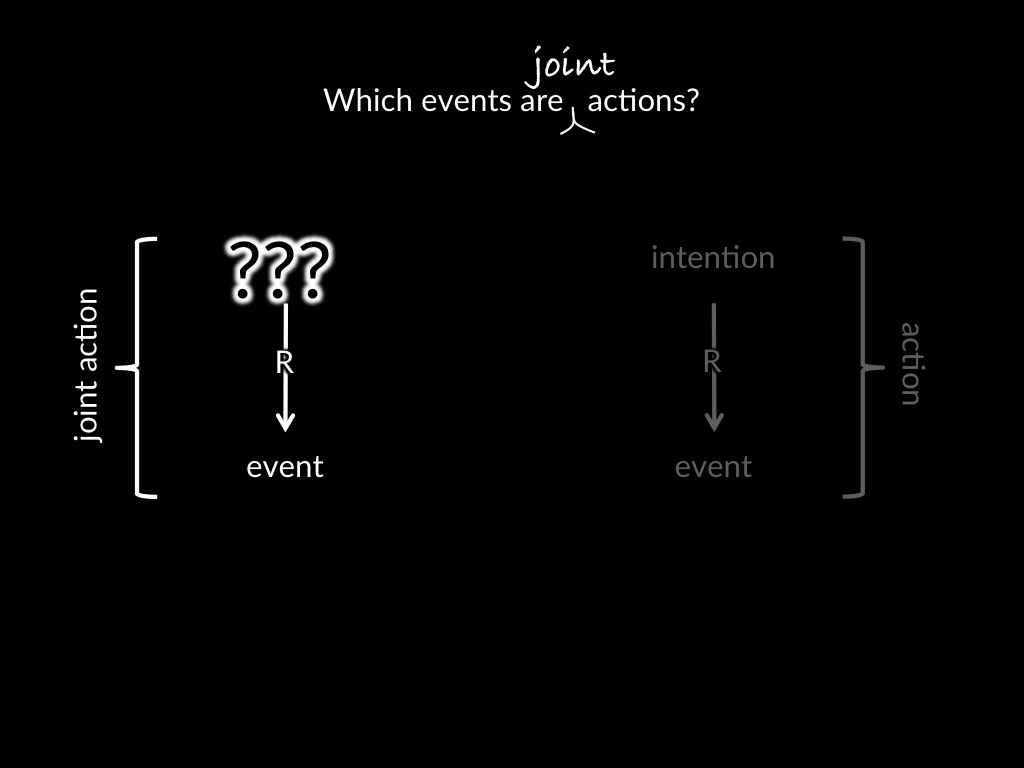

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

Any account of shared agency must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

They each intend that

they, the sisters, cycle to school together.

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

1. I intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

2. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

3. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together by way of you forcing me into the back of my car.

Walking Together in the Tarantino Sense

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Walking together in the Tarantino sense

1. I intend that we, you and I, walk together.

... by means of my forcing you at gun point.

2. You intend that we, you and I, walk together.

... by means of you forcing me at gun point.

the threat of collapse: trading intuitions

another contrast case: blocking the aisle

1. The sisters perform a joint action; the strangers’ actions are parallel but merely individual.

2. In both cases, the conditions of the Simple View are met.

therefore:

3. The Simple View does not correctly answer the question, What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Is it a genuine counterexample?

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

The Simple View

‘each agent does not just intend that the group perform the […] joint action.

‘Rather, each agent intends as well that the group perform this joint action in accordance with subplans (of the intentions in favor of the joint action) that mesh’

(Bratman 1992: 332)

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Bratman on Shared Intention

‘three main concerns: conceptual, metaphysical, and normative.

‘We seek an articulated conceptual framework that adequately supports our theorizing about modest sociality;

‘... to understand what in the world constitutes such modest sociality;

‘and ... an understanding of the kinds of normativity—the kinds of ‘oughts’—that are central to modest sociality.

‘And throughout we are interested in the relations—conceptual, metaphysical, normative—between individual agency and modest sociality.’

Modest sociality:

‘small scale shared intentional agency in the absence of asymmetric authority relations’

Braman 2009, p. 150

the continuity thesis

‘once God created individual planning agents and ... they have relevant knowledge of each other’s minds, nothing fundamentally new--conceptually, metaphysically, or normatively--needs to be added for there to be modest sociality.’

Bratman (2015, p. 8)

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities,

(b) coordinate planning, and

(c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

>>>

creature construction

Bratman (2015, p. 32)

step 1

‘Our shared intention to paint together involves your intention that we paint and my intention that we paint.’

Bratman (2015, p. 12)

(Compare the Simple View)

the ‘mafia case’* motivates ... and painting the house different colours motivates ...

step 2

We each intend that we paint by way of the intentions that we paint* and by meshing* subplans of these intentions.

why??

step 3

‘there is common knowledge among the participants of the conditions cited in this construction’

Bratman (2015, p. 58)

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

weekly seminar tasks

lecture: too much discussion?

Department UG Culture Survey

https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/philosophy/people/eqandwelfare/survey

Two Objections to Bratman

‘Our shared intention to paint together involves your intention that we paint and my intention that we paint.’

Bratman (2015, p. 12)

‘the team intention ... is in part expressed by "We are executing a pass play." But ... no individual member of the team has this as the entire content of his intention, for no one can execute a pass play by himself.’

Searle (1990, pp.~92--3)

the own-action condition:

‘it is always true that the subject of an intention is the intended agent of the intended activity’

Bratman (2015, p. 13)

Is it a genuine requirement?

the settle condition:

‘intentions . . . are the attitudes that resolve deliberative questions, thereby settling issues’

Velleman (1997, p. 32)

Does Bratmans’s view

violate the settle condition?

A solution?:

(a) if we both do as we intend, we will paint

(b) our intentions that we paint are interdependent*

(The persistence of my intention is interdependent with the persistence of yours, and this is because ...)

conclusion