Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

\def \ititle {Lecture 04}

\def \isubtitle {Joint Action}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

shared intention

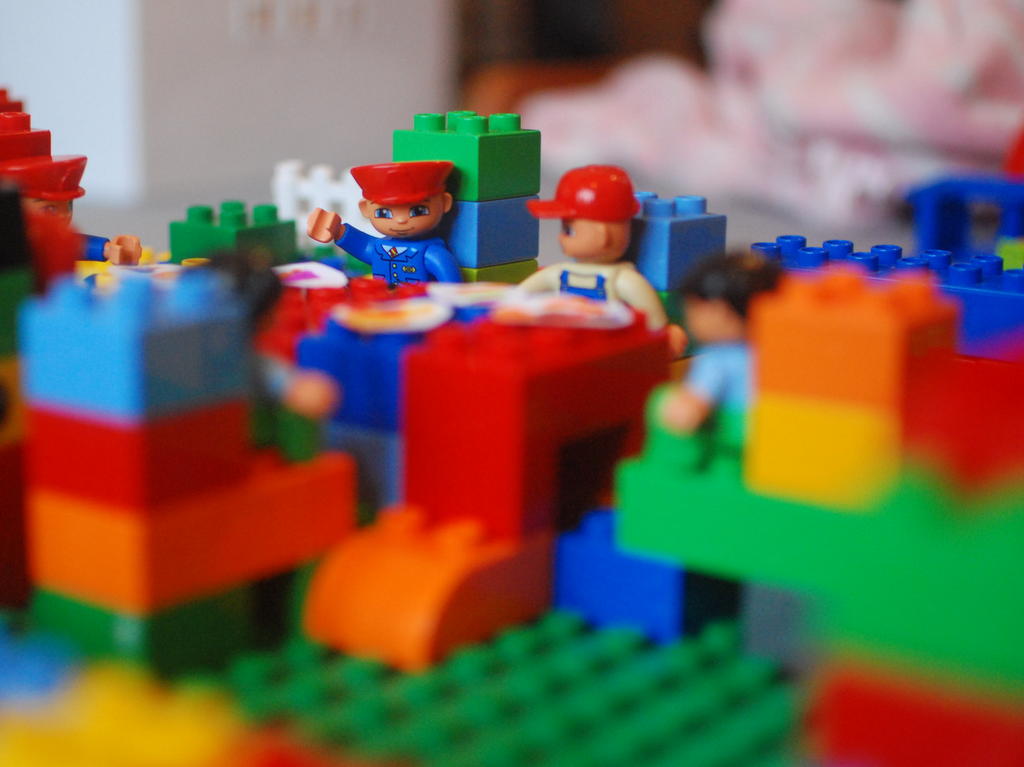

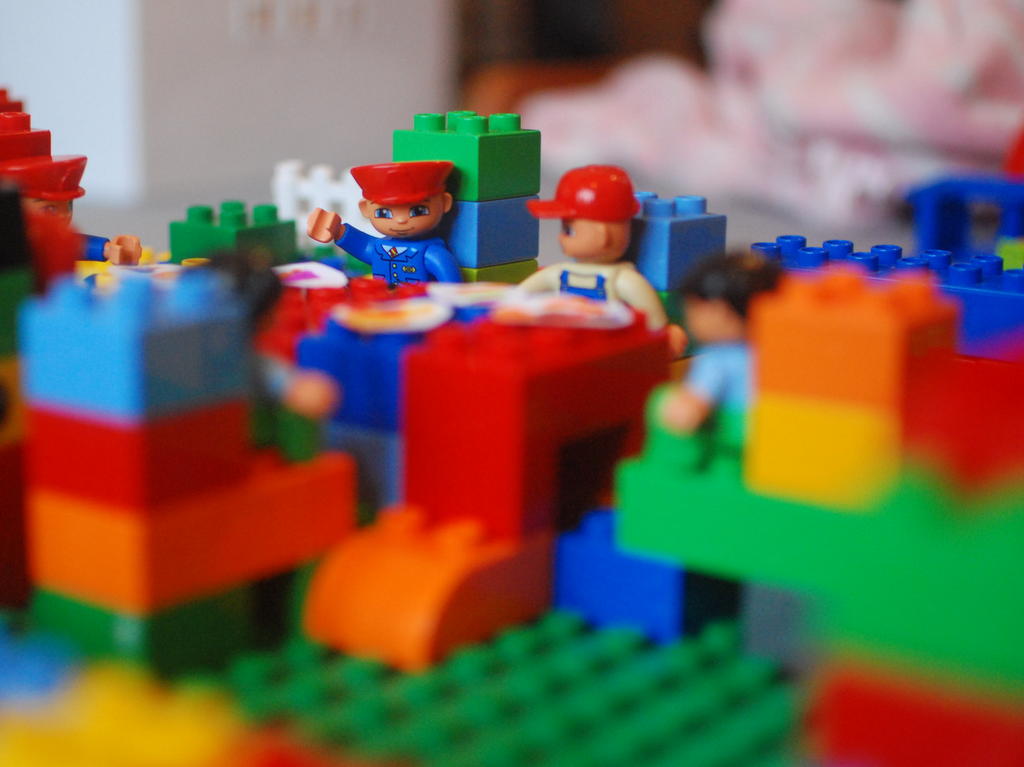

Our current task: understand what shared intention is.

Why? Because it should help us to characterise what distinguishes joint actions from

parallel but merely individual actions.

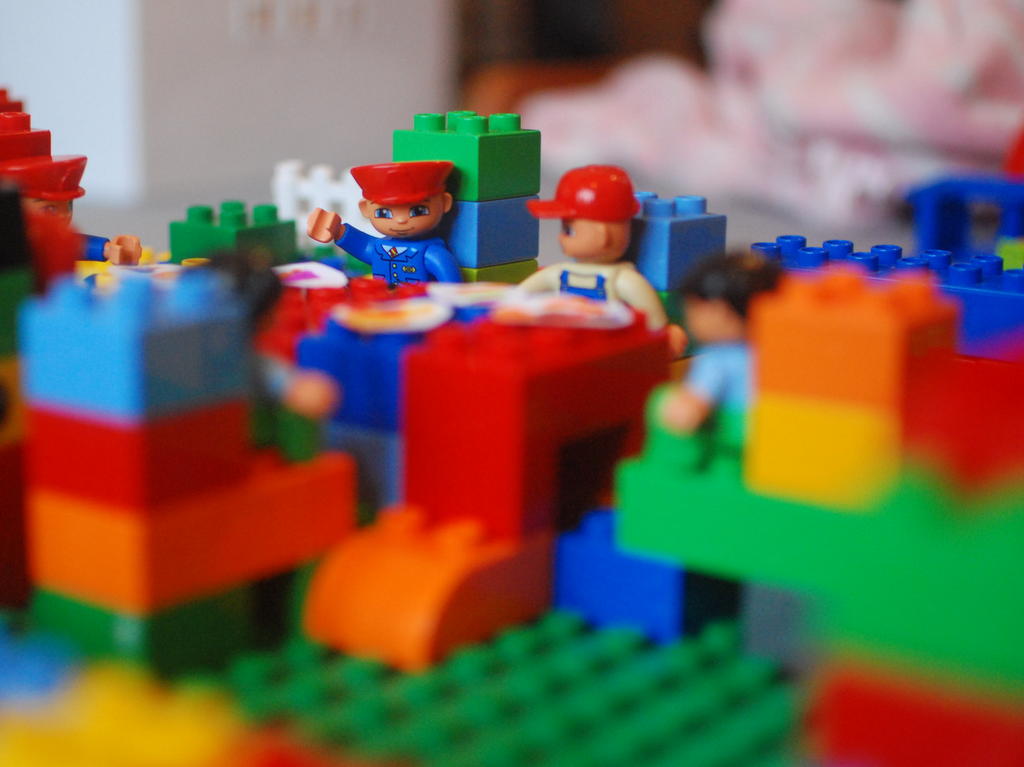

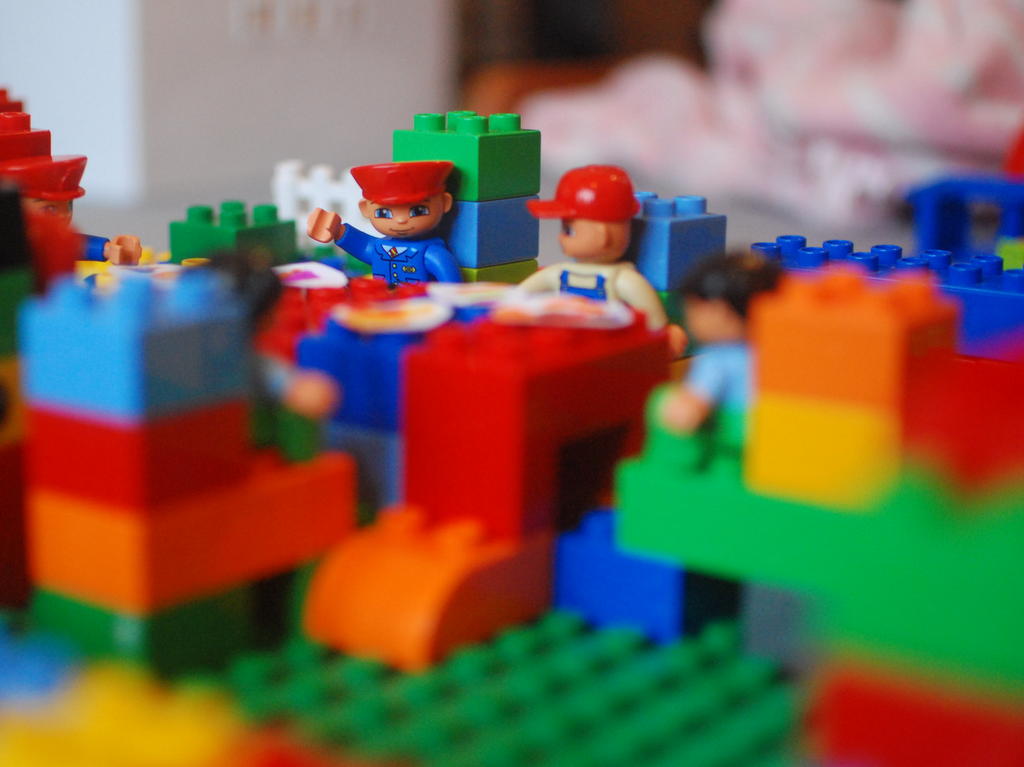

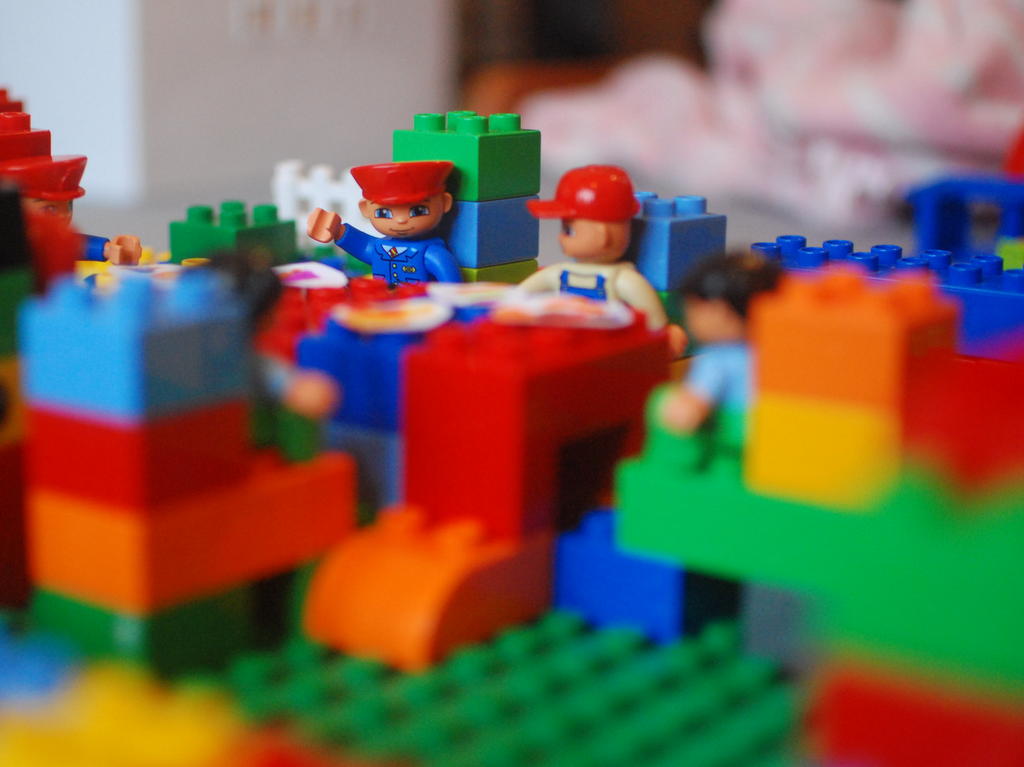

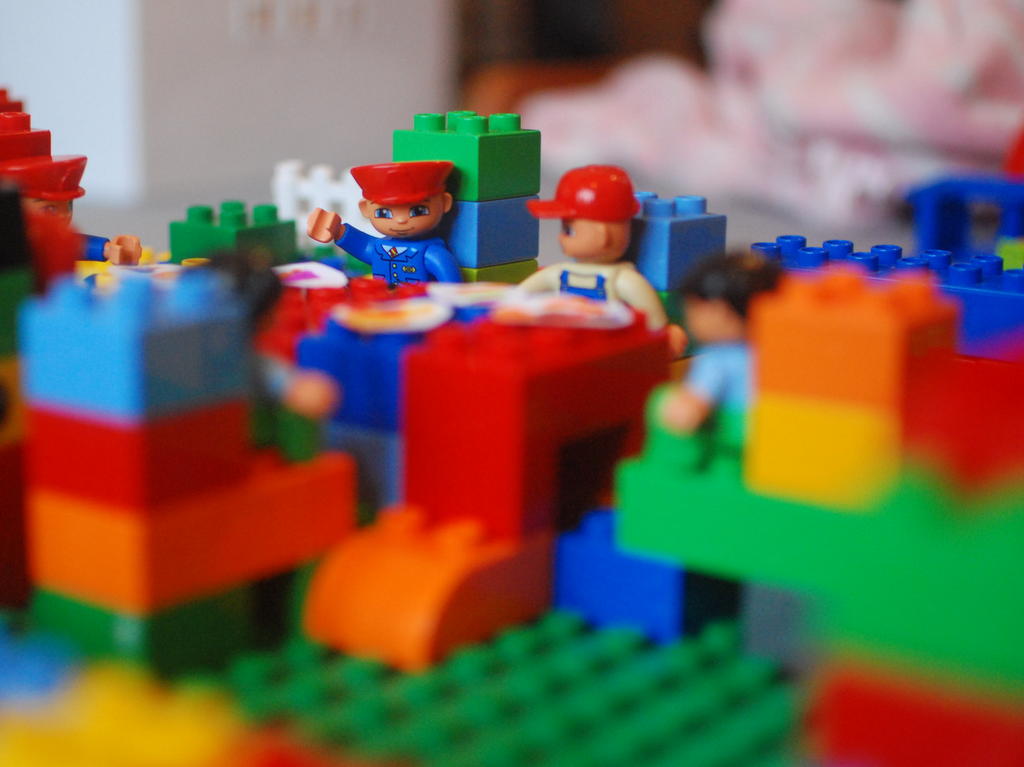

(These men are having dinner together, unlike those on the table next to them

who are eating in parallel but merely individually.)

Last time we saw that there is an objection to Bratman’s account of shared intention.

This was a counterexample to the sufficiency of the conditions he gives,

which suggests that he is wrong to thing that interconnected planning is sufficient

for shared intention.

This motivates considering an alternative approach, one centring on commitment ...

today:

joint commitment

(It will take us a while to get to joint commitment; first we’ll just think

about commitment.)

\section{Commitment in Shared Agency}

Are there forms of commitment which are somehow associated with shared intention?

Margaret Gilbert and Abe Roth (among several others) have argued that there are.

What are the key features Gilbert identifies, and what arguments does Roth offer?

Intentions are associated with commitments to yourself.

Intending to visit the book shop involves a kind of commitment to do so.

This kind of commitment is part of what distinguishes desire from intention ...

‘Having a desire to walk together is compatible with having a desire not to do so

... whereas, in intending, one has gone beyond the point of weighing considerations

for and against, and has committed to a course of action.’

\citep[p.~361]{Roth:2004ki}

Roth (2004, p. 361)

To put this another way: not acting on a desire is not generally a failure,

whereas not acting on an intention is generally a failure of some kind.

(This is consistent with saying that there can be overwhelmingly strong

reasons not to act on a particular intention, of course.)

What kind of commitments?

Ethical commitments? No.

What is the source of the commitments associated with intentions?

Could their source be some general ethical principles?

This seems unlikely for two reasons.

First, you might intend to do something utterly abhorrent.

While I think such intentions are associated with commitments, I don’t think

that the fact you have an intention contributes anything at all to a an

ethical evaluation of such actions.

(It’s not just that the intention is a very small consideration; it simply

has no place in ethical discussion at all.)

What about the second reason? ...

Intentions are associated with commitments *to yourself*.

(In Gilbert’s terms, the commitment is a source of directed obligations;

it is you and no one else who is obligated to ensure you act to fulfil

your intention.)

Others are not generally entitled to criticise you for failing to

fulfil intentions; or, if they are, it is usually because they have

some legitimate interest in you.

By contrast, ethical principles are not naturally thought of as

specific to you in this way.

Gilbert calls them

‘Personal commitments’

and I will suppose that they are distinctive of intentions.

How is this relevant to our interest in shared agency? ...

Shared intentions are associated with commitments to each other.

To borrow an example from Abe Roth and Margaret Gilbert (Roth 2004, p. 363),

consider two people who have a shared intention that they walk.

Suppose one person walks too fast for the other to keep up.

The other person has a special ground for criticising the first.

As I say, this is a great insight.

It’s also a source of Gilbert’s eventual downfall, I think.

But it will be useful to us.

What kind of commitments?

So shared intention is associated have a kind of commitment that is neither

a personal commitment nor, apparently, one that has an ethical basis.

But what is the nature of this commitment?

A personal commitment is a commitment to oneself.

contralateral commitments between participants

Because ethical commitments are not directed.

So we have to be cautious here; we know that there is something associated with

shared intention that is neither a personal commitment nor an ethical commitment,

but we don’t yet want to commit to a theory of the nature of that thing.

Note that neither of these options obviously implies the other.

(A contralateral commitment is one that is, in part, directed to another individual;

it is not necessarily a ‘commitment by two or more people’ nor a ‘commitment of two or more people’.)

Is having a contralateral commitment just a matter of having conditional commitments?

- ‘Bob is committed to walking, on the condition that Sue is (similarly) committed.’

- ‘Sue is committed to walking, on the condition that Bob is (similarly) committed.’

‘Whether your partner has the relevant commitment is up to you.’

‘It's not even clear from the start that Bob has any commitment ...

because his commitment is, in effect, conditioned on itself (by way of the conditioning on

Sue's intention).’

\citep[p.~378]{Roth:2004ki}

Roth (2004, p. 378)

The quote continues:

‘But if Bob's intention is conditioned on itself, then

(as we saw above in the discussion of (iii)) it is not really an intention,

and, in any case, it lacks the commitment we need in order to account for shared agency.’

conclusion so far:

Intentions

are associated with

commitments to oneself.

Shared intentions

are somehow associated with

contralateral commitments.

The Objection From Contralateral Commitment

\section{The Objection From Contralateral Commitment}

A premise linking shared intention with contralateral commitments provides

the basis for an objection against Bratman’s account (among others’ accounts) of shared intention.

What is the objection and should we accept it?

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Recall the simple view ...

1. Shared intentions are associated with contralateral commitments.

This is generally taken to be an objection to the Simple View.

But what exactly is the objection?

2. Having the intentions specified by the Simple View would not entail having contralateral commitments.

(Because ‘it is unclear how one’s own intention to pursue a goal amounts to a commitment to anyone besides oneself.’ (Roth, 2004 p. 371))

To see this, consider the mafia case and related cases.

3. An account of shared agency must explain the origin of contralateral commitments.

Therefore

4. The Simple View is at best incomplete.

Why aren’t we offering a stronger conclusion?

Because the first premise is so weak. If we strengthen premise 1 to say that having shared intentions

entails having contralateral commitments, then we would have a stronger argument.

Except that it would be harder to defend premise 1.

So far we haven’t really given an argument for this second premise.

Eventually we will

consider Bratman’s argument against this third premise.

But first let’s consider how a variation on this argument can be used to object to Bratman’s

account of shared intention ...

Objection

1. The states specified by Bratman’s view are not associated with contralateral commitments.

2. An account of shared agency must explain the origin of contralateral commitments.

Therefore

3. Bratman’s view is at best incomplete.

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Recall Bratman's sufficient conditions for shared intention'

The same objection applies here: the case of

Beatrice and Baldric shows that you can meet the conditions Bratman

imposes without any contralateral commitments.

What does gilbert say in favour of this?

‘When people regard themselves as collectively intending to do something, they appear to understand that, by virtue of the collective intention, and that alone, each party has the standing to demand [...] conformity of the other parties. A joint commitment account of collective intention respects this fact. [...] accounts that do not appeal to joint commitment—such as those of Michael Bratman and John Searle—are hard-pressed to do so.’

\citep[pp.~88–9]{gilbert:2014_book}

Gilbert (2013, pp 88-9)

This is not an argument.

Never do this in your essays.

Either they can or they cannot.

Also note that the subject is an account.

A person might be hard pressed to do something; an account cannot be.

Stress ‘by virtue of the collective intention, and that alone’ in this quote.

Consider Bratman’s argument against this second premise ...

Bratman: ‘Shared intention, social explanation’

The gist of Bratman’s repsonse is this.

Yes: Shared intentions are associated with contralateral commitments.

But: the association can be explained by factors extraneous to shared agency.

Let’s see how this explanation goes ...

Note that what follows isn’t exactly what Bratman says; I’m borrowing his ideas to

respond to what I think might be a good argument from commitment against the Simple View

and, as we’ll see, against Bratman’s view.

If I assure you of something, or intentionally encourage you to rely on it,

then you are in a special position to criticise me.

The association of shared intention with contralateral commitments

is a consequence of the fact that shared intentions are often

sustained by assurance and suchlike.

Specifically, the interdependence of persistence may depend on commitments

or commitment generating things.

This would be a great essay topic: read Gilbert plus Roth (2004) on Scanlon plus Chapter 4

of Bratman’s book and try to work out who is right.

So if you accept Bratman’s view, do you think contralateral commitments are just

irrelevant in giving an account of shared agency?

Not at all because ..

Contralateral commitments sometimes enable us to have shared intentions.

How is contralateral commitment associated with shared intention?

Gilbert (and others): it’s intrinsic

Not all shared intention involves contralateral commitment.

All shared intention involves contralateral commitment.

The existence of contralateral commitments can be explained by general ethical and social facts.

The existence of contralateral commitments cannot be explained by general ethical and social facts.

Gilbert is explicit about what grounds her theorising.

‘informal observation including self-observation’ and my ‘own sense of the matter’.

(Gilbert, 2014 pp. 24, 358)

So it seems that the debate between Gilbert and Bratman cannot easily be resolved.

Let me explain what I think we should conclude.

Conclusion 1. Bratman is right at least insofar as it is not obvious whether

an account of shared agency must explain the origin of contralateral commitments.

So there is no good objection to his view here.

(People sometimes claim that contralateral commitments are intrinsic to shared

agency, but why accept this?)

Objection

1. The states specified by Bratman’s view are not associated with contralateral commitments.

2. An account of shared agency must explain the origin of contralateral commitments.

Therefore

3. Bratman’s view is at best incomplete.

The objection from contralateral commitments fails (as it stands).

But there is an independent objection to Bratman’s view.

(this is the counterexample with Beatrice and Baldric).

A stipulation about contralateral commitments might overcome this objection.

This is easiest to see in the mafia and Tarantino cases; people who are going to proceed as these

people do do not seem to have contralateral commitments to each other.

Conclusion 2: the observation that shared intentions are associated with contralateral

commitments might enable us to supply something that is missing.

Conclusion 3: so far we have no positive grounds to think that contralateral commitments

should actually feature in a correct account of shared agency.

Or maybe we just need joint commitments to fully understand shared agency.

Let me finish by putting this really crudely.

Our current task is to explain what distinguishes joint action from parallel

but merely individual action.

It seems we might be able to do this by invoking contralateral commitments.

What are the prospects for this idea?

Parallel but Merely Individual Action

Two people making the cross hit the red square in the ordinary way.

Beatrice & Baldric’s making the cross hit the red square

Two sisters cycling together.

Two strangers cycling the same route side-by-side.

Members of a flash mob simultaneously open their newspapers noisily.

Onlookers simultaneously open their newspapers noisily.

Two caveats ...

Contralateral commitments are associated with shared intention, not joint action.

They are plausibly features related to intention; this is why I

introduced them by analogy with individual intention.

This limits what we can hope to achieve by appeal to contralateral commitment.

Not an account of joint action, but only of the form which involves shared intention.

Still, given our progress so far even that much would be quite an achievement.

Shared intention does not require much commitment.

‘If they are walking together, both Andrea herself and Heinrich will have the understandings so far described: by virtue of their walking together Andrea has a right to Heinrich’s continued walking alongside her, together with the standing to issue related rebukes and demands.’

\citep[p.~25]{gilbert:2014_book}

Gilbert (2014, p. 25)

I think this is ridiculous (although lots do not; e.g. ‘We agree with Gilbert that

joint action goes, intuitively, with the sort of joint commitment that

she describes’ \citep[p.~32]{pettit:2006_joint}; also Helm endorses Gilbert).

‘Mightn’t one have a noncommittal attitude toward one’s walk with someone if, for example, one suspects that person might turn out to be irritable and unpleasant company?’

\citep[p.~361]{Roth:2004ki}

Roth (2004, p. 361)

I think Roth is roughly right.

The same is true concerning ordinary, individual intention.

Yes, intention, unlike mere desire, involves commitment to act;

but that commitment can be extremely fragile.

So these are the caveats I think we should accept.

If we are going to make use of contralateral commitments, we should

first spend some time trying to better understand what they are and

how they might arise.

This is my next topic ...

Gilbert on Joint Commitment

\section{Gilbert on Joint Commitment}

Can we give a reductive account of the sort of commitments associated

with shared intention? If not, how should we understand it?

In particular, is a joint commitment a commitment that two or more

people have collectively? And is Gilbert right that joint commitments

have contents of a special form?

Here is our basic picture.

Intentions are associated with commitments.

Shared intentions are associated with commitments to each other (contralateral commitments).

Gilbert thinks there is something missing from this picture: joint commitments ...

Gilbert: joint commitment

‘a commitment

by two or more people

of the same two or more people.’

Contrast personal commitment (by me, of me)

Contrast contralateral commitment (by me, of me, to you)

How should we understand the idea that the commitment is ‘by two or more people’?

I suggest that this is simply a matter of collective predication.

joint commitment is ‘the collective analogue of a personal commitment’

\citep[p.~85]{gilbert:2014_book}

Gilbert (2013, p. 85)

To explain,

recall something we talked about a lot back in lecture 1 ...

Here are two sentences:

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

I suggest that the contrast here is clear, and isn’t particular to

psychological or normative states.

Their thoughtless actions soaked Zach’s trousers.

- ambiguous (really!)

There are also cases which are ambiguous.

(Note that the ambiguity is real; if affects how many times Zach’s trousers

must have been soaked for the sentence to be true.)

I also want to suggest that the fundamental distinction between personal

and joint commitments is of the same kind ...

Ayesha and Beatrice are committed to walking

- also ambiguous (?)

- when collective, it is a joint commitment

So my question was,

How should we understand the idea that the commitment is ‘by two or more people’?

I’ve suggested that this is simply a matter of collective predication.

I should warn you, however, that this isn’t something Gilbert actually says,

and it isn’t obvious to me that this must be her view.

Gilbert: joint commitment

‘a commitment

by two or more people

of the same two or more people.’

Contrast personal commitment (by me, of me)

Contrast contralateral commitment (by me, of me, to you)

joint commitment is ‘the collective analogue of a personal commitment’

Gilbert (2013, p. 85)

Gilbert: joint commitments entail contralateral commitments.

I’ve been suggesting that

A joint commitment is a commitment we have collectively.

so

A joint commitment is a commitment.

Compare: a collective blocking is simply a blocking.

This explains why there may not be very much to say about what joint commitments

are, and in particular, why a reductive account may not be needed.

Distributive / Collective / Shared

\section{Distributive / Collective / Shared}

We need a three-fold contrast between distributive, collective and shared.

distributive

vs

collective commitment (or intention)

vs

shared intention (or commitment)

Ayesha and Beatrice played the horse in our pantomime.

Case 1-individual: actors who perform a role distributively (different theatres, each

performs the role)

vs

Case 1-collective: actors who perform a role collectively (one plays the back of the

horse, the other plays the front of the horse)

Case 1-individual: actors who perform a role distributively (different theatres, each

performs the role)

vs

Case 1-shared: actors who share a role: one plays the character as a child,

the other plays the character as an adult. (Compare Bratman on shared intention:

Bratman)

Case 1-collective: actors who perform a role collectively (one plays the back of the

horse, the other plays the front of the horse)

vs

Case 1-shared: actors who share a role: one plays the character as a child,

the other plays the character as an adult.

Could give blame as a second example.

You have two minutes to think of another three-way contrast.

Think of Bratman on shared intention. According to Bratman, a shared intention

is something that we share in the same sense that Ayesha and Beatrice share the role

of pantomime horse when one plays the young horse and the other the old horse.

The shared intention comprises intentions and knowledge states some of which are mine

and some of which are yours.

By contrast, a collective commitment or intention would be one that we collectively have.

It’s analogous to the case where Ayesha and Beatrice join their bodies to play the horse.

(That is, we would be its plural subject.)

Are There Joint Commitments?

\section{Are There Joint Commitments?}

Do joint commitments exist?

Gilbert: joint commitment is irreducible to personal commitment

Compare blocking.

Sometimes when trying to sprint through an airport there is one sizeable

individual blocking your way, while at other times it is several people

ambling side-by-side who hold you up. If the several’s blocking your way

is not a matter of each individually blocking your way, then they are

*collectively* blocking your way. As this illustrates, some properties

permit both singular and plural, collective predication.

Is collective blocking reducible to individual actions?

Of course, collective blocking is ultimately a matter of the individual people

and their interactions.

But we can recognise this while remaining neutral on whether any

kind of informative reduction is possible.

I propose a stronger thesis

joint commitment is irreducible

If you’ve read Bratman (chapter 4 on Gilbert), you’ll know he thinks this

is terrible because uninformative.

But I think that lots of collective phenomena (including non social phenomena in

biology and elsewhere) may turn out not to have informative reductions.

And there’s plenty of informative things to say about joint commitment without

reducing it to something else.

So I don’t think irreducibility is a big deal.

Are there joint commitments?

So far I have been suggesting that a joint commitment is simply a commitment.

But when we talk about joint commitments we mean a commitment that two or

more people have collectively.

Is this possible?

For us to collectively lift the table

For Ahura to be personally committed

Are there collective infections?

- collective addictions?

- collective deaths?

- collective feelings?

- ...

Just because it is theoretically coherent doesn’t mean that it is empirically motivated.

As far as I understand her, Gilbert’s most convincing attempt to show that there

are joint commitments is an attempt to show how they come into being ...

‘what is needed, to put it abstractly, is expressions of readiness on

everyone’s part to be jointly committed [...].

Common knowledge of these expressions completes the picture.’

\citep[p.~253]{gilbert:2014_book}

Gilbert (2013, p. 253)

‘In order to \emph{create} a new joint commitment each of the would-be parties must openly express to the others his readiness together with the others to commit them all in the pertinent way. Once these expressions are common knowledge between the parties, the joint commitment is in place—as they understand’

\citep[p.~311]{gilbert:2014_book}

‘this is pretty much the whole story’

Gilbert (2013, p. 48)

‘[i]t is not clear that there is any very helpful way of breaking down the notion

of expressing one’s readiness to be jointly committed’ \citep[p.~48]{gilbert:2014_book}

‘this is pretty much the whole story regarding the creation of a basic

case of … joint commitment’ \citep[p.~48]{gilbert:2014_book}.

Not: I’m ready if you are.

(Because this would get us back into Roth’s problem that the readiess

is conditional on itself.)

Compare: For us to collectively lift the table,

what is needed is expressions on everyone’s part

of readiness to lift the table.

No, we also have to actually lift it.

Why think that,

what is needed is an expression of readiness on Ahura’s part to be committed.

Does it work for the individual case?

I don’t think so.

Ahura can be ready to commit and can express his readiness without

actually getting around to committing.

If Ahura’s readiness does constitue a commitment on his part,

it is surely readiness to act or something rather than readiness

to commit.

Another attempt on how joint commitments get established...

Are there joint commitments?

‘Jessica says, “Shall we meet at six?” and Joe says, “Sure.”’

This is the phenomenon Gilbert is analysing. She says it amounts

to expressions of readiness. But put that aside.

Is it plausible that this could explain how joint commitments are formed?

Joint or merely symmetric contralateral commitments?

Here I think it is unobvious that the commitments are joint rather than

merely contralateral commitments.

(Recall that Jessica and Joe have contralateral commitments if each

has a personal commitment to the other.)

So are there joint commitments?

Maybe.

Gilbert hasn’t shown that there are.

Even so, I want to continue to explore Gilbert’s view.

If joint commitments can solve our problems, then we could look harder

for reasons to suppose that they exist.

What are the problems that joint commitments might solve for us?

Here’s the first ...

So where have we got to? I claim that claims 1 and 2 are inconsistent, as are claims 1 and 3.

1. A joint commitment is a commitment we have collectively.

(So joint commitment is a commitment.)

2. Gilbert shows joint commitments exist.

3. Joint commitments ground contralateral commitments.

I have no idea which claims we should reject.

Unless we reject 2 and 3, Gilbert is so catastrophically wrong that it seems

we must have misunderstood her.

Further some philosophers and some psychologists accept Gilbert’s view;

e.g.:

‘We agree with Gilbert that joint action goes, intuitively, with the sort of joint commitment that she describes.’

\citep[p.~32]{pettit:2006_joint}

On the other hand, you could take a completely different view.

You might say Gilbert is not radical enough and that joint commitments

allow us to make sense of plural subjects in a more robust sense than

interests her. You might say, the point of joint commitments isn’t to allow

us to make sense of the contralateral commitments, but to allow us to make

sense of the idea that commitments and mental states can be had by collectives.

But if we don’t reject 2 and 3, it seems we must reject 1, and without this

it seems we have no idea what joint commitments could be.

This is also implausible; surely Gilbert has explained this.

To be honest I suspect that I am missing something.

But I have no idea what it is.

In any case, I want to finsih with a quick look at how Gilbert

applies her account of joint commitment.

If the applications seem illuminating, that would motivate further

consideration of her research.

‘Sue is in a special position to criticize Jack when he walks too fast.’

Roth (2004, p. 364)

‘the parties to a joint commitment are in an important sense obligated to conform to the commitment. Notably, the obligation in question is directed : … one is obligated to the other parties to conform to the commitment.’

Gilbert (2013, p. 367)