Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

\def \ititle {Lecture 06}

\def \isubtitle {Joint Action}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

\section{Aggregate Subjects: Recap}

In what ways might the notion of an aggregate subject help us to understand

which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

To answer this question, we first need to consider a more basic question:

How can aggregate subjects exist?

In a previous lecture we considered the suggestion (developed by Pettit and List among others) that

aggregate subjects arise as a conseuqence of individuals representing

them.

Why do should we consider other suggestions?

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

What distinguishes joint action from parallel but merely individual action?

In the first part of this course we saw that there are reasons to reject

both the Simple View and Bratman’s view (a counterexample, no less),

and significant challenges to extracting

an answer to these questions from Gilbert’s work.

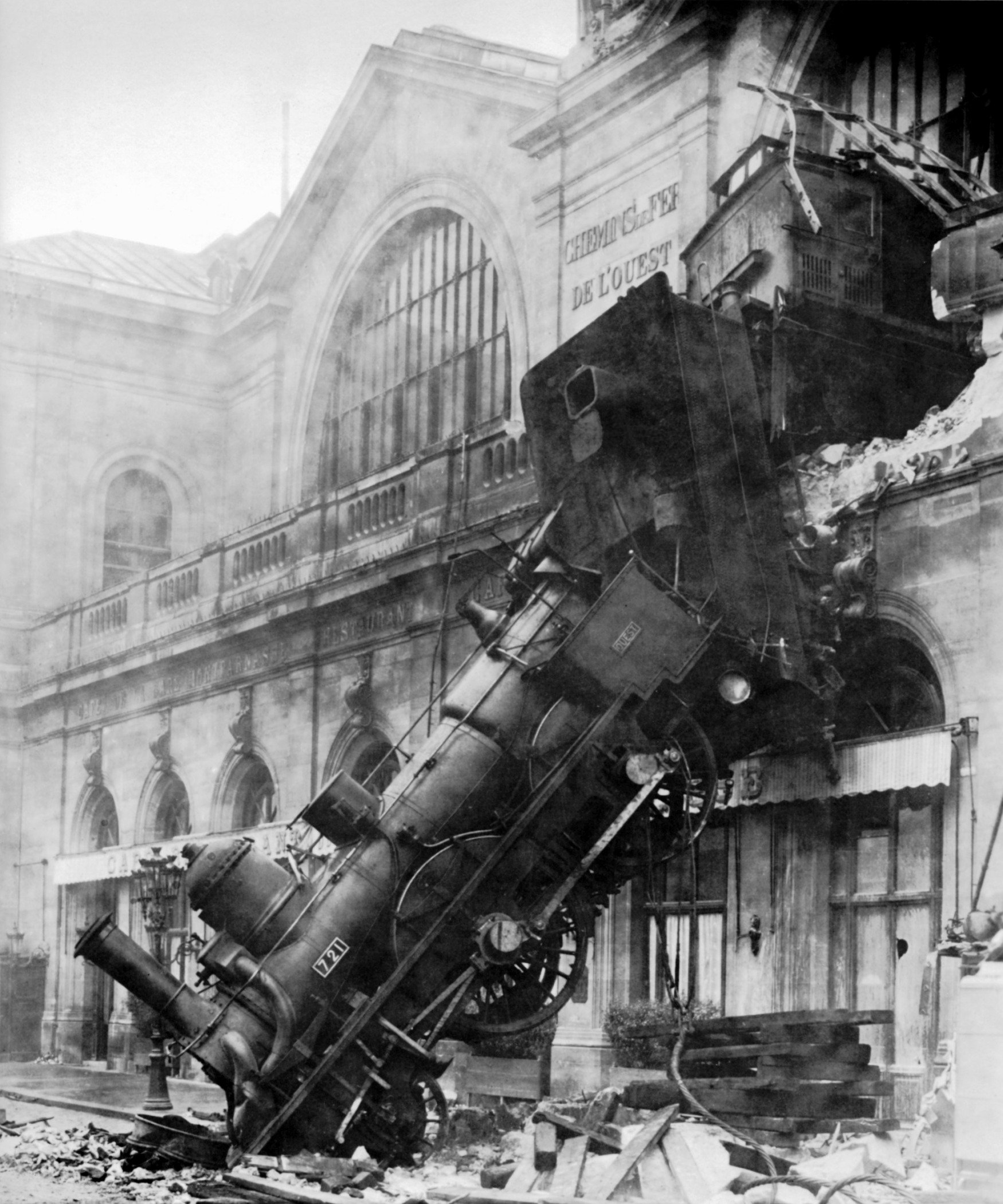

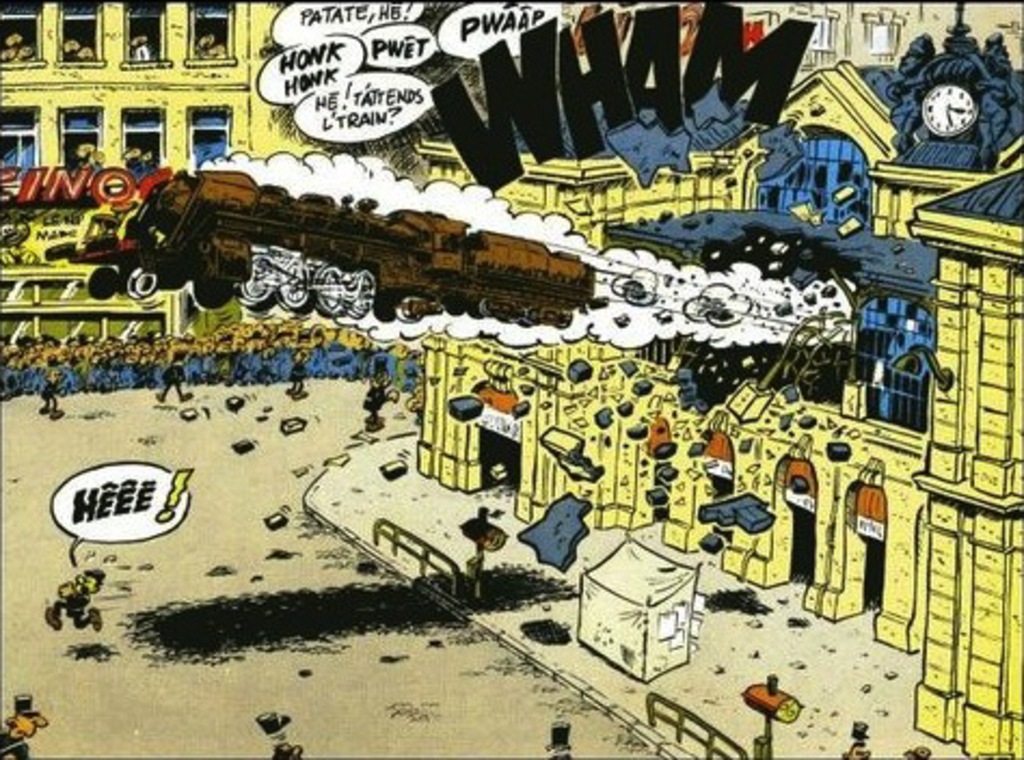

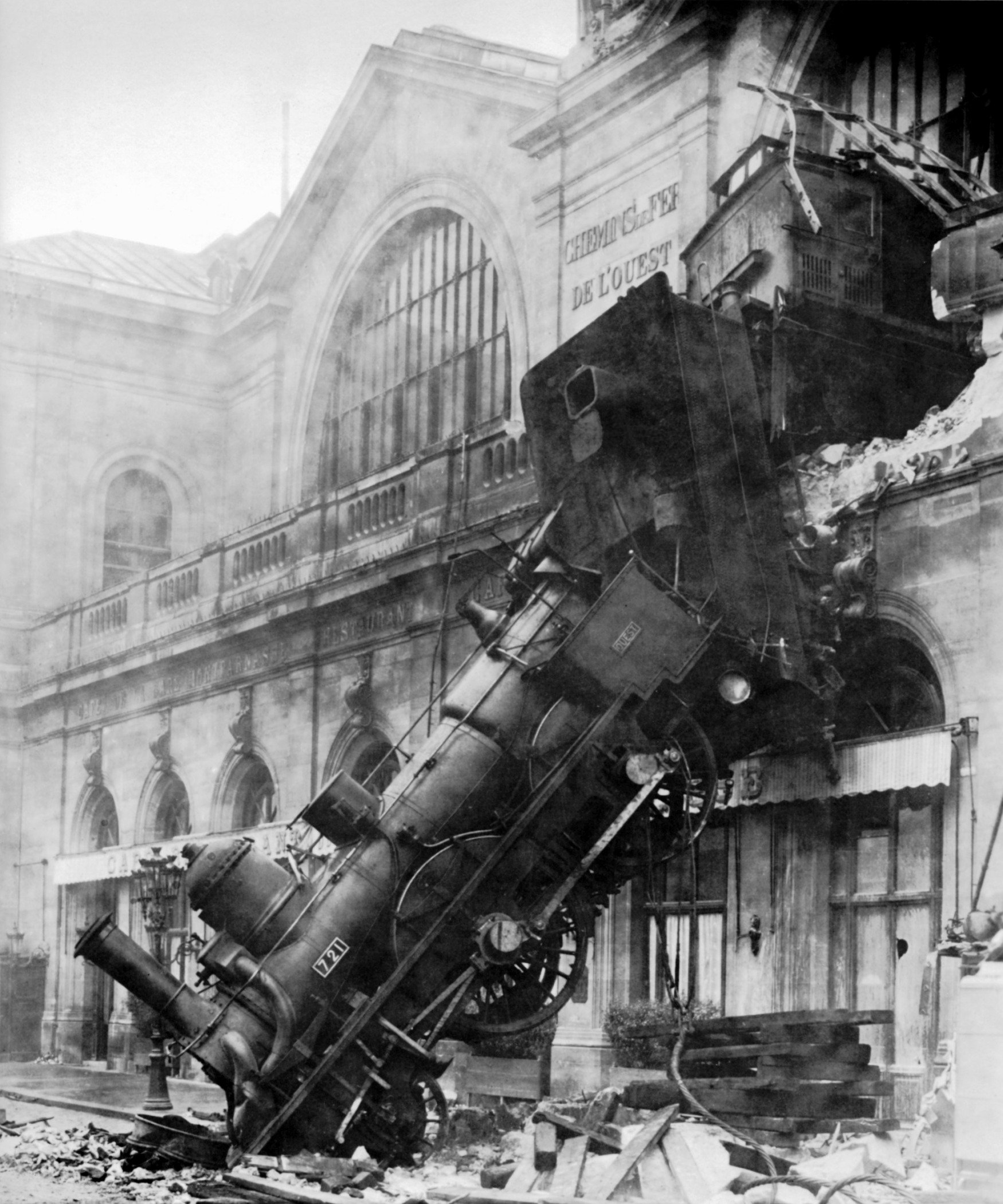

When we look at the leading accounts, it’s not much of an exaggeration

to talk about a train wreck.

Maybe we can get further by adopting a more radical approach.

aggregate subject

The more radical approach we are in the middle of exploring

hinges on aggregate subjects.

An aggregate subject is a subject with proper parts who are themselves

subjects.

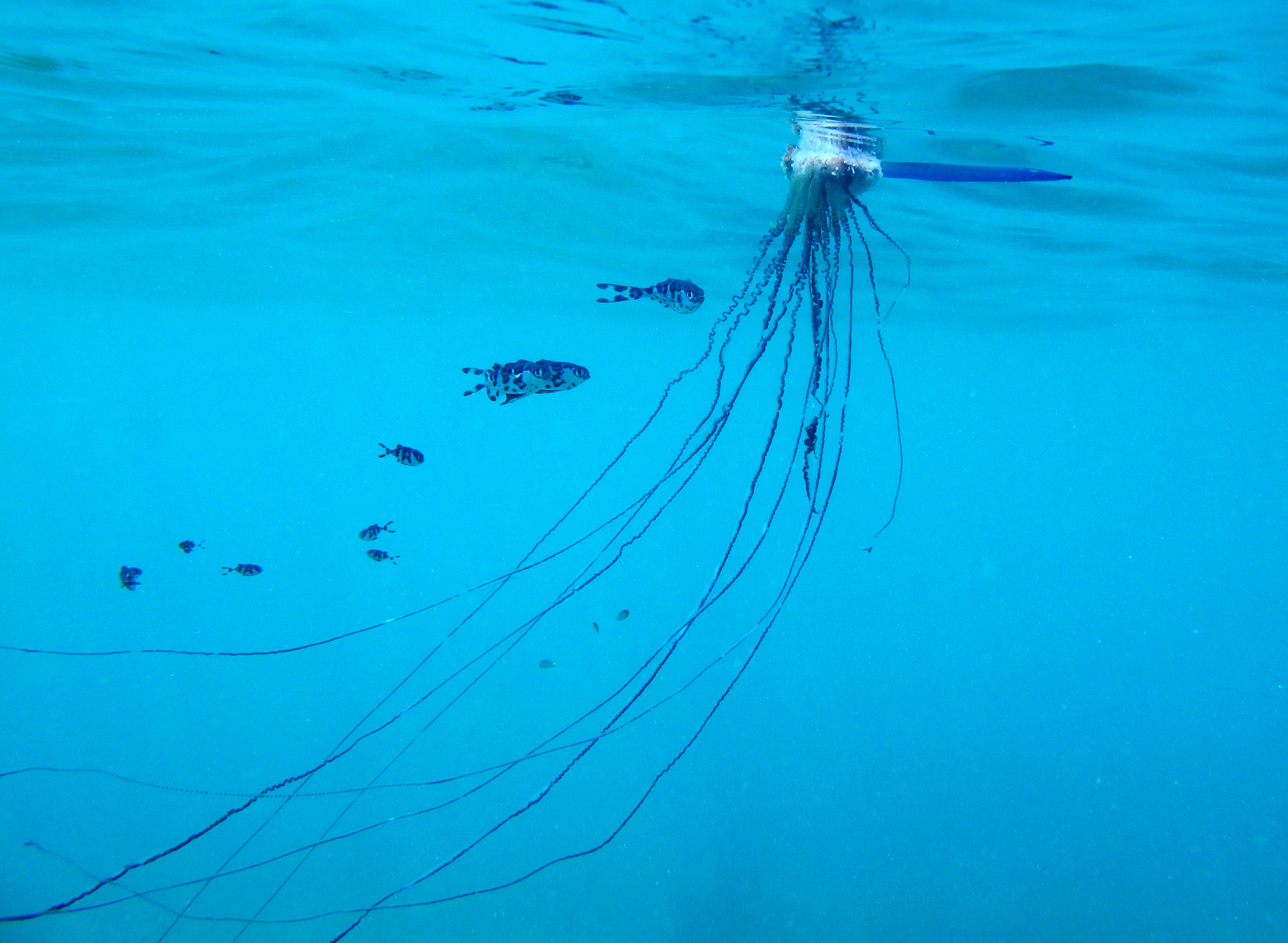

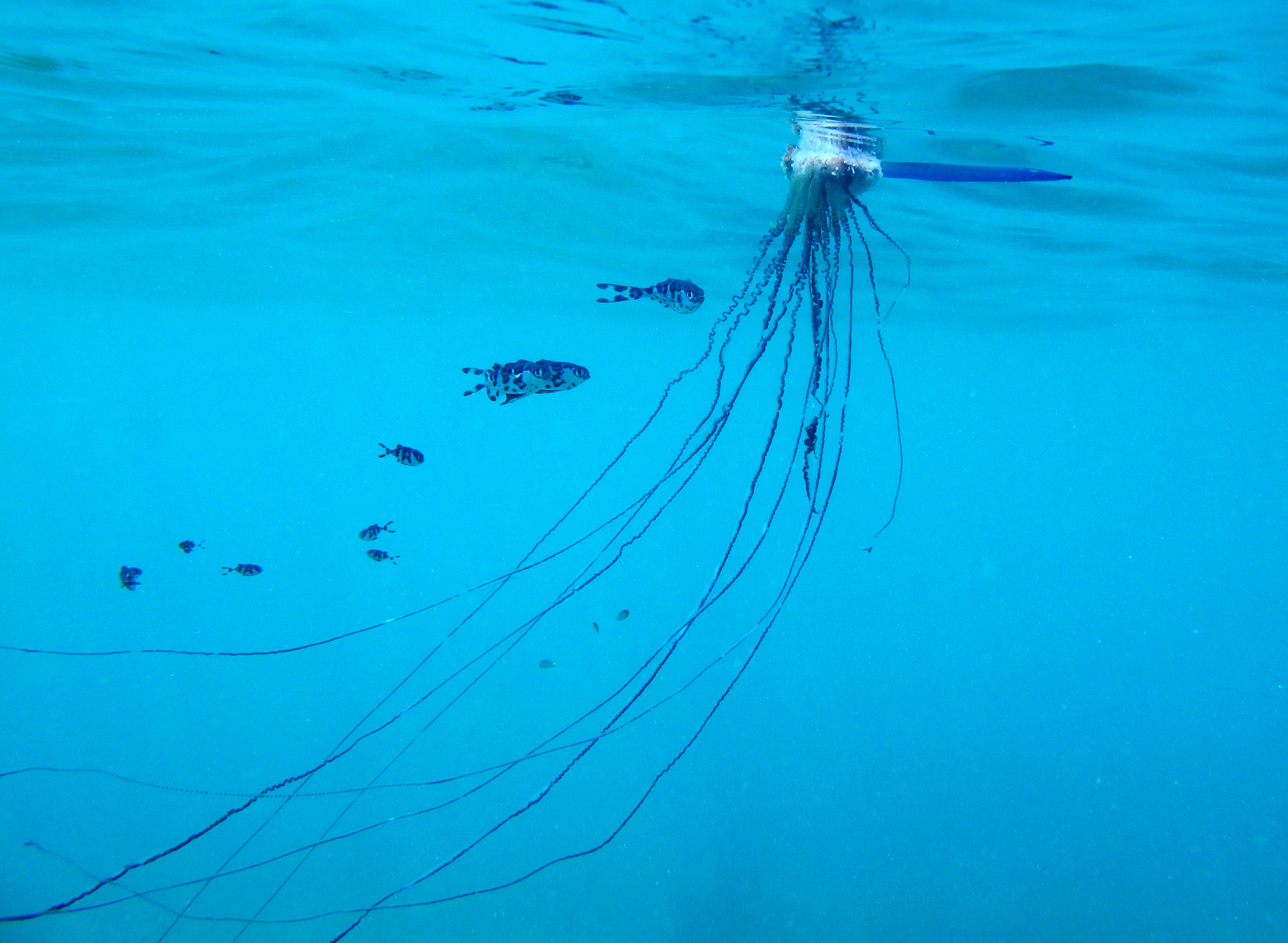

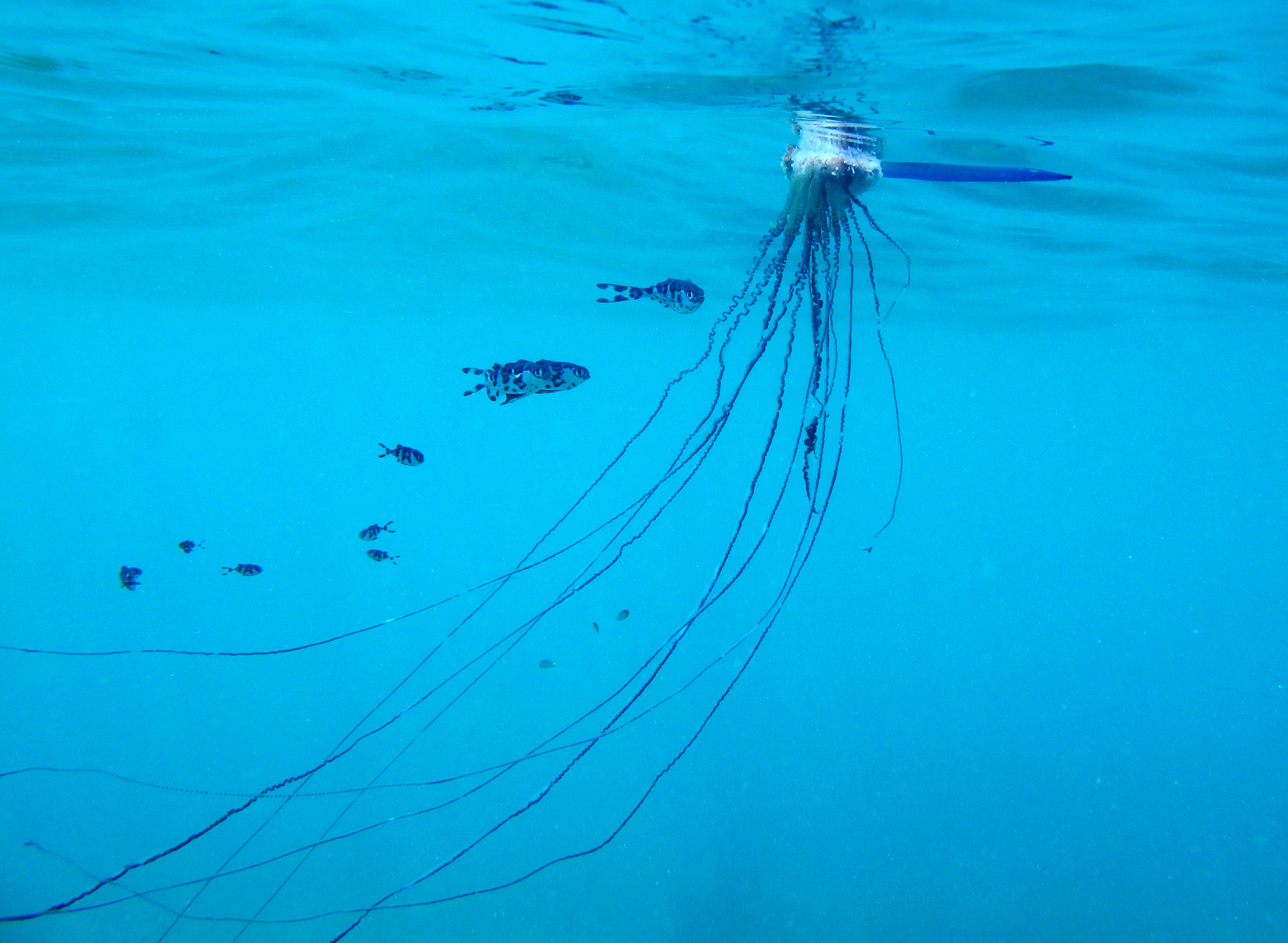

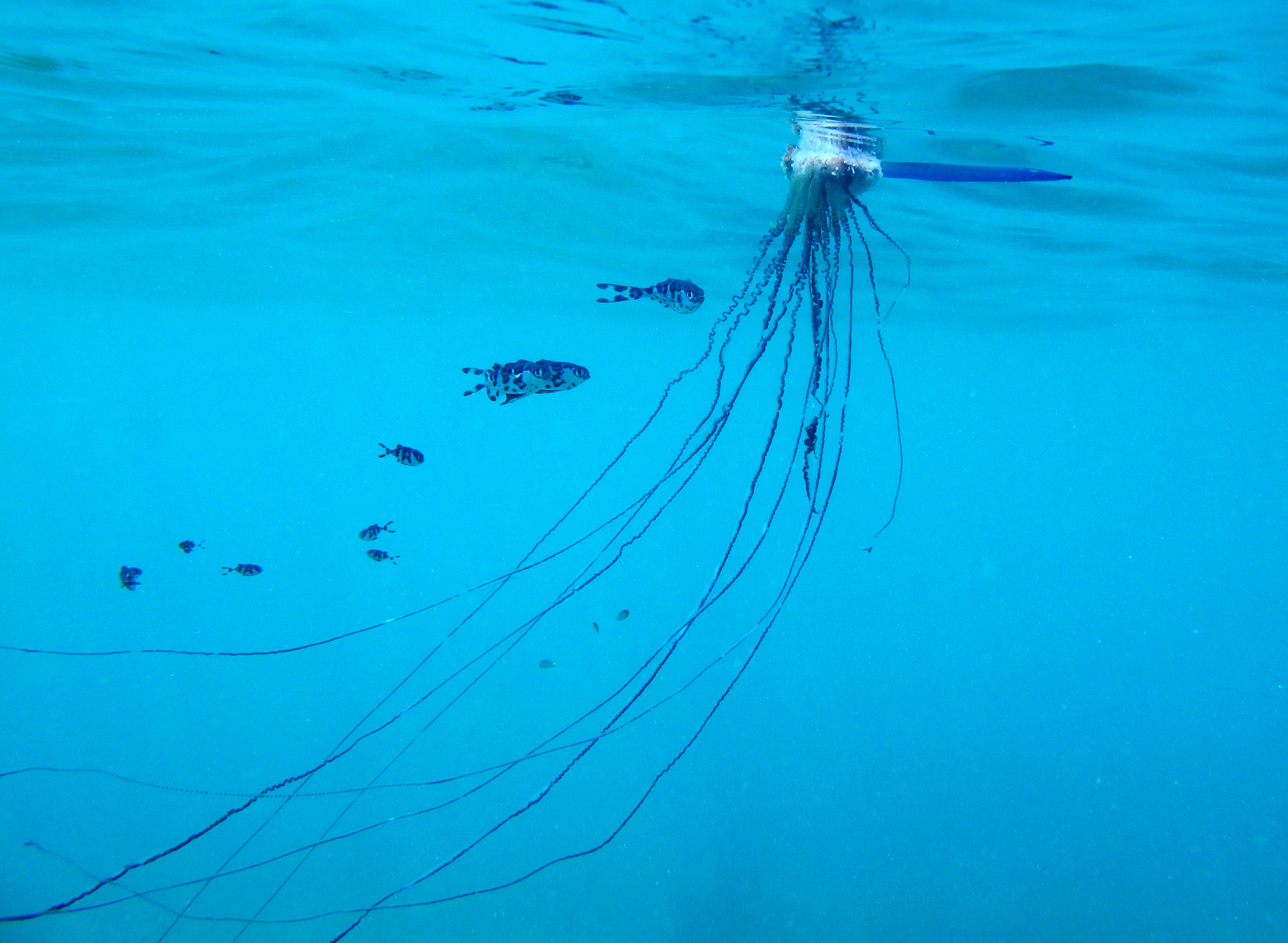

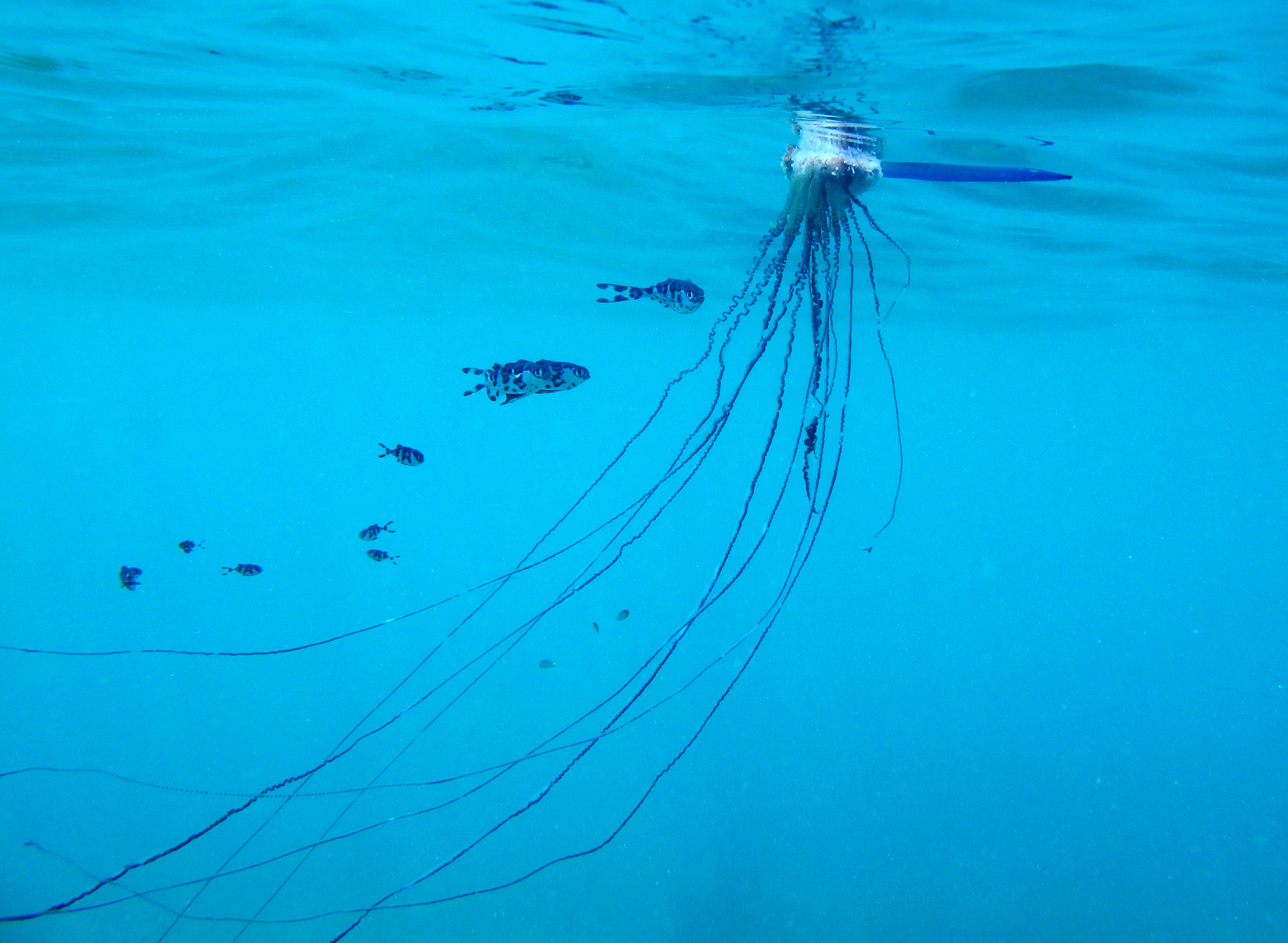

I compared aggregate subjects to an aggregate animal, the Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis),

which is composed of polyps.

Here you can say that ‘the group [of polyps] itself’ is engaged in action

which is not just a matter of the polyps all acting.

But how can such a thing exist?

Humans do not mechanically attach themselves in the way that the polyps

making up that jellyfish do.

So (as we saw in the last lecture) we have to ask, How are aggregate agents possible?

It was striking that many people took the view that such things just couldn’t exist;

just as Searle did.

One thing I aim to do in this lecture is to convince you that their existence is not

quite as strange as you might think.

But first I want to remind you of a couple of themes from the last lecture.

Self-representing Aggregate Subjects

\section{Self-representing Aggregate Subjects}

How can aggregate subjects exist?

Humans do not mechanically join to one another in the way that the polyps

making up an aggregate animal do.

What is the glue that binds an aggregate agent together?

One suggestion (developed by Pettit and List among others) is that

aggregate subjects arise as a consequence of individuals representing

them.

aggregate subject

How can such a thing exist?

Humans do not mechanically attach themselves in the way that the polyps

making up that jellyfish do.

So how are aggregate agents possible?

Dennett: Intentional Stance

Are you familiar with Dennett’s intentional stance and Dennett's ingeneous twist?

‘What it is to be a true believer is to be … a system whose behavior

is reliably and voluminously predictable via the intentional strategy.’

\citep[p.\ 15]{Dennett:1987sf}

Dennett 1987, p. 15

If we accept this, then it is easy to see how there could be aggregate subjects.

There are aggegrate subjects just in virtue of the fact that people

sometimes behave in a way that they form a system whose behaviour is

reliably and voluminously predictable via the intentional strategy.

But I think this is unsatisfying for two kinds of reason.

One is very general: the twist in the intentional stance is almost certainly

wrong, as I think even Dennett now acknowledges.

The other is that this approach neglects the subject’s own perspective.

Doesn’t it matter whether, from the perspective of the subjects themselves,

there is an aggregate agent? (This is just a hunch, not an argument.)

Cordula’s Imperative

Cordula’s Imperative: Theorise about shared agency from the point of view of the subject.

Humans from around two years of age or earlier can readily attribute

states to an imaginary agent, identify how it needs to act given

those states and perform actions on its behalf.

Note that in acting on behalf of imaginary agents they may be

furthering their own real-world objectives (as in `Teddy wants to go to the park.').

Joint action sometimes involves imaginary agents as well---not teddies, of course,

but imaginary composite agents.

Lucina and Charlie each want to complete a multi-step task.

Lucina imagines that she and Charlie are an aggregate subject, Lucina-and-Charlie, and

attributes to this imaginary agent the intention of completing the task.

Charlie does the same, ascribing the same intention to the imaginary agent.

Do such imaginary activities presuppose shared intentions?

Certainly we require something to make it the case that

it is not merely an accident that Charlie imagines the same agent and

attributes the same intention as Lucina.

%\footnote{The case described here is not one of joint acton \emph{with} an imaginary agent. The actual agents, Lucina and Charlie, are real. But what makes their action interestingly joint is the fact that they each construe themselves as acting on behalf of an imaginary composite agent, Lucina-and-Charlie.}

This is a

joint action in that Lucina and Charlie work together to achieve

an outcome which occurs as a common effect of their actions.

Incidentally, this case indicates that some of the functions assigned to shared

intention can be also fulfilled by imaginings. Charlie and Lucina

construe their actions as if they were the actions of a single agent,

and it is this imaginary exercise which makes them responsive to each

others' actions and causes them to coordinate their activities by executing

complementary parts of what must be done on behalf of the imaginary agent.

What does this get us?

An imaginary aggregate subject.

But is there more?

More than an imaginary aggregate subject?

‘The intentional or conversational stance not only enables us to identify and understand

patterns that would escape [...] an individualistic stance [...]

In the case of self-representing agents, it is also responsible for

generating the very patterns that appear in the interaction between them. [...]

the perspective is of the greatest importance in understanding agency’

\citep[p.~1658]{pettit:2014_group}

Helm’s position appears similar: ‘a basic account of what must

be the case if there are to be plural agents: there must be a projectible pattern of

rationality in the group’s responses constitutive of an evaluative perspective held

jointly by members of the group, such that each of us can be held rationally accountable

for his or her responses in light of that joint evaluative perspective’

\citep[p.~38]{helm_plural_2008}

Also: ‘he is a member of a plural agent whose evaluative perspective he both

shares and helps constitute; that is, we each must care about us as a plural agent.’

\citep[p.~40]{helm_plural_2008}

Pettit (2014, p. 1658)

imaginary -> reflectively constituted

aggregate subject

aggregate subject

The question was, how could there be any such thing as aggregate subjects

given that humans don’t mechanically attach themselves to each other in the way that

polyps do.

Following Pettit and List, I suggested that one answer to this involves self-reflection

playing a role in constituting the aggregate subject.

Aggregate Subjects vs Plural Subjects

\section{Aggregate Subjects vs Plural Subjects}

A plural subject is

some individuals who collectively have an intention or other attitude.

An aggregate subject is

a subject with multiple parts that are subjects.

How do these differ?

As a preliminary we need to be clear about what we are getting

ourselves into with aggregate subjects, particularly as even the best

papers on this topic are not entirely clear and the terminology is

confusingly diverse.

Understanding shared agency and the (frankly mostly awful) literature on this topic

requires several distinctions. We have already covered collective vs distributive

and collective vs shared. Now it’s time for a further distinction:

Plural Subject vs Aggregate Subject.

The tiny leaves formed an impenetrable barrier

which blocked the drain.

Let’s start with a super-simple analogy (I hope this isn’t too simple).

If some tiny leaves collectively block a drain, they are the plural subject of the blocking.

By contrast, suppose some tiny leaves form an impenetrable barrier which blocks the drain.

The impenetrable barrier, although composed of nothing but the leaves, is distinct from the leaves.

Similarly, if we collectively intend or believe something (assuming such a thing is possible),

we (not something distinct from us, but simply you and I) are the plural subject of that intention or belief.

If we are components of an aggregate, or members of a group, that intends or believes something,

then there is an aggregate subject (not you and I but something distinct from, albeit composed from, us)

which intends or believes.

This about a plural subject, the tiny leaves.

This about an aggregate subject, the impenetrable barrier.

With this in mind, let’s step back and get our teminology straight.

1. What is a subject?

--- An individual who has an intention or other attitude.

A subject is a bearer of intentions or other mental states.

2. Singular vs plural quantification

This is logic.

You can quantify over individuals (somebody ate my breakfast)

and you can quantify over pluralities (some people ate my breakfast).

-- A flea is bothering me [singular]

-- Some fleas are bothering me [plural]

Ontological Innocence

(Background: note that here I assume that the right theory of plural quantification is

one which exemplifies what \citet{Linnebo:2005ig} calls \emph{Ontological Innocence}.

That is, it is a theory which ‘introduces no new ontological commitments to sets

or any other kind of “set-like” entities over and above the individual objects

that compose the pluralities in question’ \citep{Linnebo:2005ig}.

There are several reasons for thinking that this is a requirement on any

adequate theory of plural quantification, but the best is Boolos’ point that

‘It is haywire to think that when you have some Cheerios, you are

eating a \emph{set}---what you're doing is: eating THE CHEERIOS’ (Boolos quoted

in \citep[p.~295]{Oliver:2001ha}.

I was planning at one point to introduce you to research in logic on plural quantification,

but in the end I thought that maybe we could skip that in the lectures.

If you’re interested, read \citet{Linnebo:2005ig}.

)

Assumption: the right theory of plural quantification exemplifies \emph{Ontological Innocence}.

That is, it is a theory on which plural quantification

‘introduces no new ontological commitments to sets

or any other kind of “set-like” entities over and above the individual objects

that compose the pluralities in question’ \citep{Linnebo:2005ig}.

Compare Boolos:

‘It is haywire to think that when you have some Cheerios, you are

eating a \emph{set}---what you're doing is: eating THE CHEERIOS’ (Boolos quoted

in \citealp[p.~295]{Oliver:2001ha}).

For more on plural quantification, read \citet{Linnebo:2005ig}.

3. Distributive vs collective predication

4. What is a plural subject?

-- Some individuals who collectively have an intention or other attitude.

A \emph{plural subject} is

some individuals who collectively have an intention or other attitude.

This is what we defined: the plural subject. (Not everyone uses the term in this way,

but they should.)

Suppose, as I think, that Gilbert’s joint commitments are commitments that some

individuals collectively have.

Then Gilbert says that the people who collectively have a commitment are a plural subject.

This is exactly how I’m using the term.

Likewise if we collectively have an intention, knowledge state, belief or emotion,

then we are a plural subject in this sense.

1. What is a subject?

--- An individual who has an intention or other attitude.

A subject is a bearer of intentions or other mental states.

2. What is an aggregate (or ‘colonial’) animal?

-- An animal with multiple parts that are animals.

Typically the parts have specialised functions and cannot survive independently,

but, unlike the cells of a multicellualar organism, the resemble independent animals.

(The Portugese man o’ war is a colony of jellyfish-like polyps.)

Wikipedia: ‘the Portuguese man o' war is a colony of four different types of polyp or related forms’

3. What is an aggregate subject?

-- A subject with multiple parts that are subjects.

An \emph{aggregate subject} is

a subject with multiple parts that are subjects.

This is what we defined.

Note that no one else uses the term in this way.

Christian List uses the term ‘aggregate’ in relation to judgement aggregation;

this is also a sensible, but completely different, way to use the terminology.

Plural subject

-- some individuals who collectively have an attitude.

Aggregate subject

-- a subject with multiple parts that are subjects.

Identical to the individuals.

Distinct from the individuals.

When we have plural subjects, there is nothing distinct from the subjects

which is the subject of the predication.

The plural subject is identical to the individuals.

But when we have aggregate subjects, there is something distinct.

The individuals \emph{comprise} the aggregate subject but the aggregate

subject is not \emph{identical} to those individuals.

This is potentially confusing because the aggregate subject might be

nothing but an aggregate of the individuals who are the plural subject.

Could not involve other individuals.

May involve other individuals.

Still we know they are different because different counterfactuls are true

of the plural subject and of the aggregate subject.

To illustrate, the man o’ war is nothing but the polyps, but the man o’ war can

surive the loss of one polyp and the addition of another whereas the polyps can’t

(they aren’t *these* polyps anymore if there is one missing or one addded).)

True: Collectively form an aggregate subject.

False: Does not form an aggregate subject.

Even where there is a plural subject and an aggregate subject and the componets

of the aggregate subject are the plural subject, still different things

can be true of the aggregate subject and of the plural subject

For example, he animals that comprise an aggregate animal do collectively

comprise an aggregate animal; but the aggregate animal itself does not

comprise an aggregate animal.

False: Do not collectively sting or eat.

True: Does sting and eat.

For example, an aggregate animal, the Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis),

stings and eats but the animals (polyps) that compose it

do not collectively sting or eat.

Pettit, List, Helm, ?Gilbert

The philosophers whose current focus is plural subjects or aggregate subjects.

Note the contrast between e.g. Pettit (aggregate subject) and Schmid (plural subject)

According to Schmid, ‘Feelings can indeed be shared in the simplest sense of the word,’

the sense in which

‘sharing is not a matter of type, or of qualitative identity (i.e. of having different

things that are somehow similar), but a matter of token, or numerical identity’ (2009, p. 88).

On Schmid’s view, there are plural subjects of emotions.

This neither entials, nor is entailed by, the claim that there are aggregate subjects of emotions.

Why is Gilbert tentatively on both sides? Let’s take a look ...

Recall that Gilbert’s analysis of joint commitment has two parts.

Gilbert on joint commitment

[1] The subject:

‘a commitment

by two or more people

of the same two or more people.’

Here I interpret Gilbert as saying that the commitment is something we collectively have.

By comparison, consider our being collectively obliged to mitigate the effects of global warming.

None of us are individually obliged to do this (how could we?), but collectively we are.

[2] The content:

All joint commitments are commitments to emulate, as far as possible, a single body which does something (2013, p. 64).

It’s just here I think there’s room to see an aggregate agent.

Although Gilbert doesn’t write this explicitly (as far as I recall),

it would be coherent to suppose that our emulating a single body

brings an aggregate agent into being.

‘some of the things we may share an intention to do are designed for two or more participants

... Sally and Tim are jointly committed to intend as a body to produce, by virtue of the

actions of each, a single instance of a tennis game with the two of them as participants in

that game’ (Gilbert 2013, p. 117)

Self-representing Aggregate Subjects Presuppose Joint Action

\section{Self-representing Aggregate Subjects Presuppose Joint Action}

Suppose that an aggregate subject exists in virtue of several individuals

(self-)representing themselves as that aggregate subject.

Could this enable us to understand what distinguishes joint action from

parallel but merely individual actions?

The basic idea is this.

Some

aggregate subjects exists in virtue of several individuals

(self-)representing themselves as that aggregate subject.

self-representation and aggregate agents

Some aggregate subjects exists in virtue of several individuals(self-)representing themselves as that aggregate subject.

No claim that this is the only way an aggregate subject could exist.

(Team reasoning may be an alternative, as may certain forms of parallel planning.)

Objections:

-- intellectualist

(depends on members thinking of themselves as members of a group)

-- long-term

Seems to depend on long-term collaboration, or at least the potential for it

‘A corporate attitude (of a collective) is an attitude held by the collective as an

intentional agent. To say that a collective holds a corporate belief or desire in

some proposition p is to say that the collective is an agent in its own right,

which holds that belief or desire. Thus not all collectives are capable of

holding corporate attitudes; only those that qualify as group agents are.

For example, the United States Supreme Court and other collegial courts arguably

fall into this category, as do commercial corporations, NGOs, and other purposive

organizations such as cohesive political parties, universities, and especially states.

In consequence, they are capable of holding corporate attitudes. By contrast, a random

collection of individuals, such as the people who happen to be on Times Square at a

particular time, does not. Such a collection cannot hold corporate attitudes.’

\citep[p.~1615]{list:2014_three}

-- depends on shared intention

What kind of attitudes must individuals have towards a group agent in

order to bring it into being? Typically they need a shared intention (which they may have

prior to constituting a group agent) to form a group.

‘we shall abstract from some differences between these approaches and adopt the

following stipulative approach, broadly inspired by Bratman (1999). We say that

a collection of individuals ‘jointly intend’ to promote a particular goal if

four conditions are met:

Shared goal. They each intend that they, the members of a more or less salient collection, together promote the given goal.

Individual contribution. They each intend to do their allotted part in a more or less salient plan for achieving that goal.

Interdependence. They each form these intentions at least partly because of believing that the others form such intentions too.

Common awareness. This is all a matter of common awareness, with each believing that the first three conditions are met,

each believing that others believe this, and so on.’

\citep[p.~33]{list_pettit:2011}

-- inferrential integration

The aggregate agent is something with a life of its own, which you may influence

but certainly do not control.

So *if* we said (and I don’t think Pettit does) that having a shared intention is a

matter of the aggregate agent having an intention, we would

fails the to meet the requirements on inferential and normative integration of shared intentions

with intentions.

This is not to say there aren’t such things as aggregate agents that result

from shared intentions or other attitudes towards the aggregate agent.

My point is just that these can hardly be foundational.

Note especially that this is no objection to List & Pettit given their aims; just qualifications

on what we can achieve by borrowing their ideas.

‘Since a joint action can be an isolated act performed jointly by several individuals,

it does not necessarily bring into existence a fully fledged group agent in our sense

... In particular, the performance of a single

joint action is too thin ... to warrant the ascription of a unified agential

status ... For example, in the case of fully fledged agents

... we can meaningfully hypothesize about how they would behave

under a broad range of variations in their desires or beliefs, whereas there is a severe limit

on how far we can do this with a casual collection that performs a joint action. Moreover, any

collection of people, and not just a group with an enduring identity over time, may perform a

joint action, for instance when the people in question carry a piano downstairs together or

spontaneously join to help a stranger in need. Thus mere collections may be capable of joint

agency, whereas only groups are capable of group agency in the stronger sense we have in mind.

However, joint actions, and the joint [shared] intentions underlying them, may play a role in the

formation of group agents’

\citep[n.~18, pp.~215-6]{list_pettit:2011}

aggregate subject

The question was, how could there be any such thing as aggregate subjects

given that humans don’t mechanically attach themselves to each other in the way that

polyps do.

Following Pettit and List, I suggested that one answer to this involves self-reflection

playing a role in constituting the aggregate subject.

This idea clearly works if you agree with Dennett on the intentional stance.

It may not work if you don’t accept his view.

This leaves us with a question ...

Dennett: Intentional Stance

‘What it is to be a true believer is to be … a system whose behavior

is reliably and voluminously predictable via the intentional strategy.’

\citep[p.\ 15]{Dennett:1987sf}

Dennett 1987, p. 15

If not, can there be aggregate agents?

Although this is an interesting question, I will not pursue it here.

For suppose that the answer is yes (or that the Intentional Stance claim is true.)

Even in that case, aggregate agents do not straightforwardly help us to solve the

basic problem we face in trying to give a theory of the forms of shared agency which

characterise our social nature ...

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

my provisional conclusion

Forming aggregate agents requires joint action.

Because forming aggregate agents requires joint action,

we cannot appeal to aggregate agents in attempting to answer the question,

What distinguishes ...

\section{Team Reasoning}

‘You and another person have to choose whether to click on A or B.

If you both click on A you will both receive £100, if you both click on B you will both receive £1,

and if you click on different letters you will receive nothing. What should you do?’

(Bacharach 2006, p. 35)

Team reasoning is a game-theoretic attempt to explain what makes your both choosing A rational.

But what is team reasoning? And how is team reasoning relevant to questions about joint action?

This unit provides the barest outline. The aim is not to explain, but to make you aware that

there’s a body of research in this area.

How to create an aggregate subject?

1. self-representation (just done)

2. team reasoning?

There is further, alternative motivation for considering team reasoning.

Some have claimed that it will provide us with a ground-level account of shared

intention, and thereby of shared agency ...

‘The key difference between the two kinds of intention is not a property of the intentions themselves, but of the modes of reasoning by which they are formed. Thus, an analysis which starts with the intention has already missed what is distinctively collective about it’

\citep{Gold:2007zd}

So these researchers, unlike Pettit and List are aiming to capture a basic

form of shared agency rather than to build on a prior account of shared intention.

But there’s more ...

‘collective intentions are the product of a distinctive mode of practical reasoning, team reasoning, in which agency is attributed to groups.’

\citep{Gold:2007zd}

So these researchers are aiming to build a kind of aggregate subject.

They think, in a nutshell, that aggregate subjects are not only a consequence

of self-reflection, but can also arise through (a special mode of) reasoning

about what to do.

Gold and Sugden (2006)

But what is team reasoning? I’m so glad you asked ...

‘somebody team reasons if she works out the best possible feasible

combination of actions for all the members of her team, then does

her part in it.’

\citep[p.~121]{Bacharach:2006fk}

Bacharach (2006, p. 121)

These are the questions you would want to answer if you were going to pursue team

reasoning. In this lecture series I decided there isn’t time to do that this year.

1. What is team reasoning?

2. In what sense does team reasoning give rise to aggregate agents?

3. How might team reasoning be used in constructing a theory of shared agency?

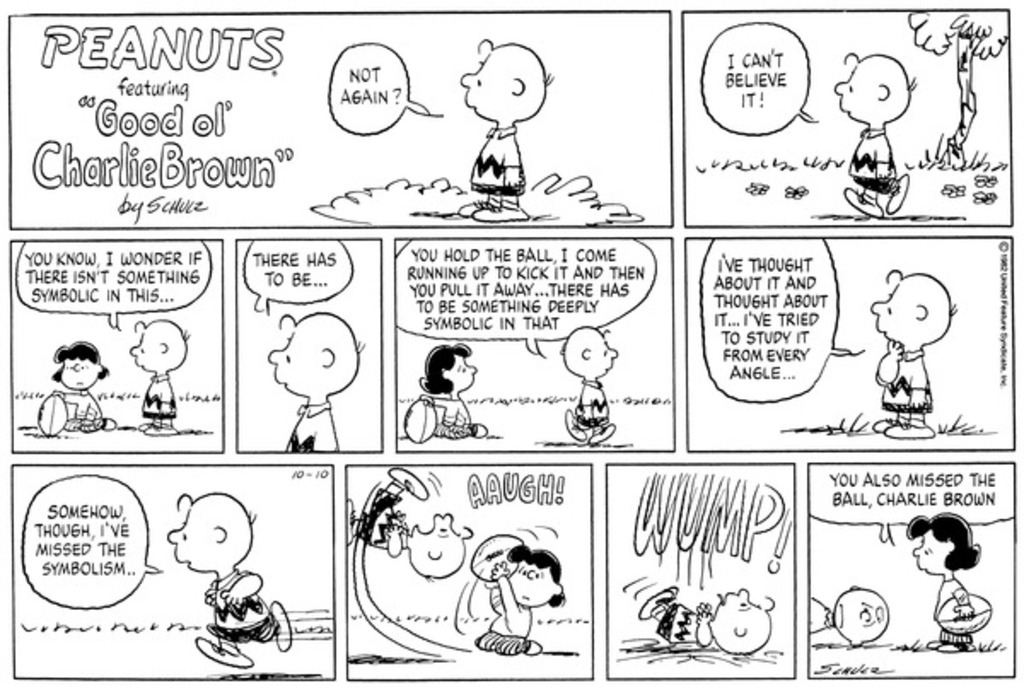

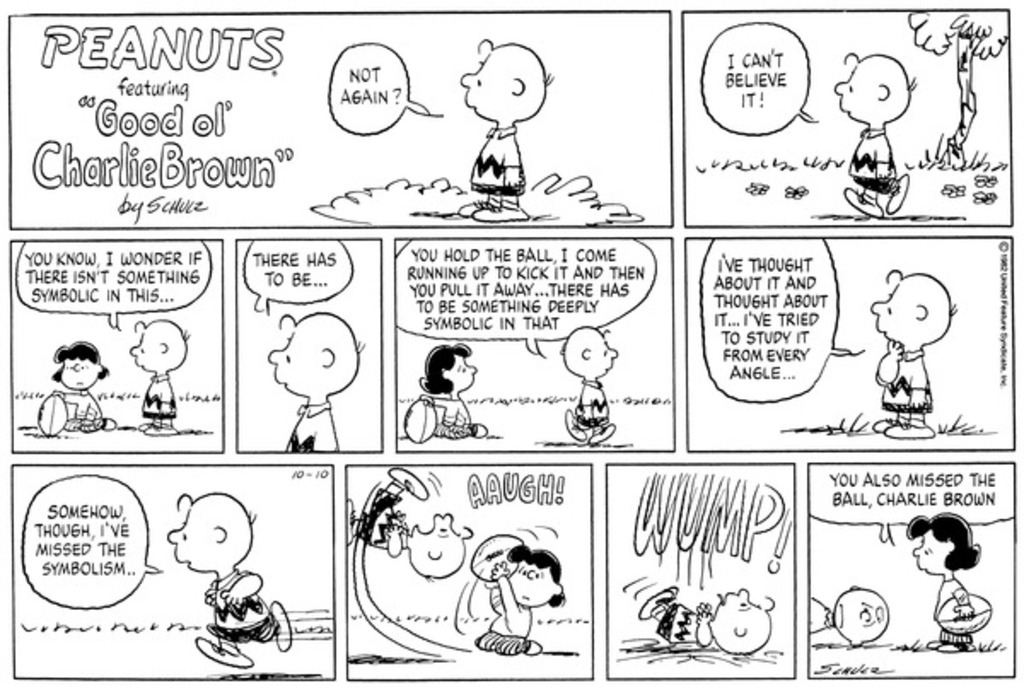

Schmid’s ‘Charlie Brown Phenomenon’

\section{Schmid’s ‘Charlie Brown Phenomenon’}

The the Charlie Brown phenomenon is

‘the possibility of being intentionally engaged in a joint action in a situation

in which overwhelming evidence to assume that the others will not do their part

is recognized to exist’ (Schmid 2013, p. 54).

What does the existence of this phenomenon suggest about shared agency?

‘participants in joint action are usually focused on whatever it is they are

jointly doing rather than on each other. Where joint action goes smoothly,

the participants are not thinking about the others anymore than they are

thinking about themselves’

\citep[p.~37]{Schmid:2013}

Schmid (2013, p. 37)

I don’t think this observation is an argument or an objection, but it

is suggestive.

In Pacherie’s account, we need beliefs about the others and their

team reasoning.

In Bratman’s account we need intentions about others’ intentions.

‘cooperators normatively expect their partners to cooperate; they do not predict their cooperation’

Dominant View: ‘the representation of the participation of the others has a mind-to-world direction of fit.’

Alternative View: ‘the representation of the participation of the others has a world-to-mind direction of fit.’

\citep[p.~38]{Schmid:2013}

Schmid (2013, p. 38)

Ok, this is just an assertion. What’s the argument for it ...

‘As his intention was to hit the ball rather than just to try to hit the ball,

Charlie’s intention either represents Lucy (cognitively) as doing her part

(holding the ball steady) or at least is incompatible with the belief that

Lucy will not hold the ball. Already in the 1950s, it becomes increasingly

clear that Lucy will pull the ball away. This evidence is further corroborated

over the following decades. Therefore, Charlie should not be optimistic. By

continuing to intend to kick the ball, it seems that Charlie violates the sufficient

reason condition. As he has reason to believe that Lucy will pull away the ball,

there is insufficient reason for optimism that he will be able to kick it.

‘Thus, in the view developed so far, and endorsed by such authors as

John Searle (2010), Raimo Tuomela, and Michael Bratman, there must be something

structurally wrong with Charlie’s intentionality; in his right mind, he cannot

intend to kick the ball. According to this line of analysis of joint action,

Charlie is simply unreasonable.’

BUT: ‘People think that Lucy rather than Charlie is at fault’ (Schmid 2013, p. 46)

Participants reason about what team-directed preferences require (so do not distinguish themselves from others).

‘participants in a joint action represent their partners as doing their parts in the same way as individual intentions implicitly represent the agent as continuing to be willing and able to perform the action until the intention’s conditions of satisfaction are reached’

‘individual agents of temporally extended actions “represent” their own future intentions and actions in the same way in which cooperators represent their partners’ intentions and actions.’

\citep[p.~49]{Schmid:2013}

Schmid (2013, p. 49)

How do cooperators represent their partners’ actions?

‘this representation is neither (purely) cognitive nor (purely) normative, but rather a very peculiar combination of the two. ’

\citep[p.~50]{Schmid:2013}

Compare representing your own actions:

‘An individual with a purely cognitive stance toward his own future self’s behavior and no normative expectation is a predictor of his behavior rather than an intender of his future action; similarly, an individual with a purely normative stance toward his own future behavior is a judge over [...] his future behavior rather than an agent.’

\citep[p.~50]{Schmid:2013}

Schmid (2013, p. 50)

I don’t want to go all the way with Schmid. In particular, I don’t quite

accept his suggestion that

‘A cooperator’s basic attitude toward his partner is such that he (implicitly) assumes that by representing the other as doing his part he makes it more likely that the other will in fact do his part because it provides the other with a motivating and a normative reason to do so.’ (p. 50)

How can we turn these observations into a theory?

Recall that we want a theory in order to be able to distinguish genuine joint

action from parallel but merely individual action.

PS: Are we still talking about aggregate agents?

Yes: from the point of view of the agents. (If Schmid is right, the basic

attitude I have towards your actions does not distinguish your actions from mine.)