Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Question

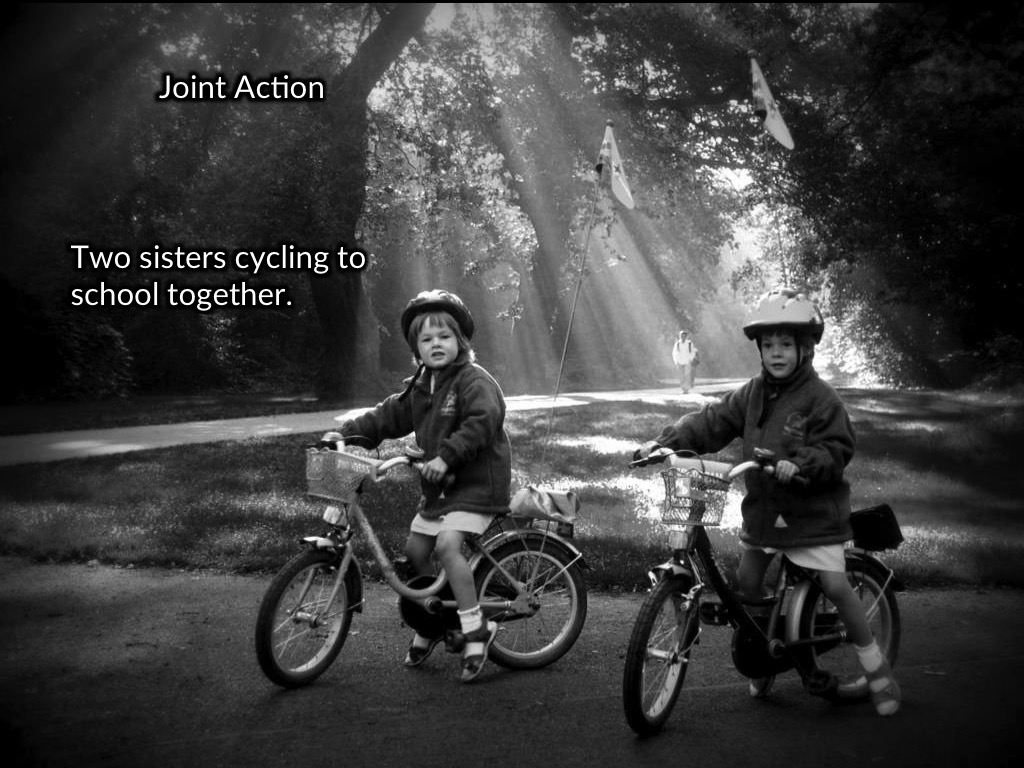

Let’s start by trying to get a pre-theoretical handle on the notion of joint action.

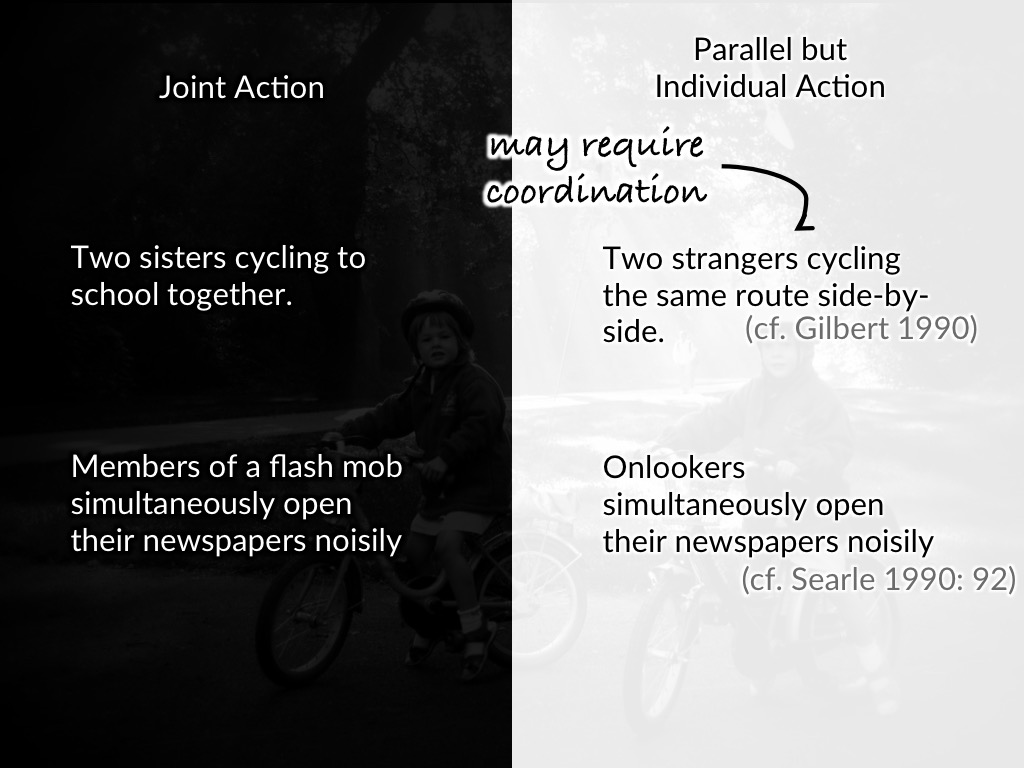

I’ve already given you some examples, but it’s even better to use contrast cases ...

You have two minutes to think of another pair of examples which contrast joint action

with parallel but merely individual action.

Give another contrast pair.

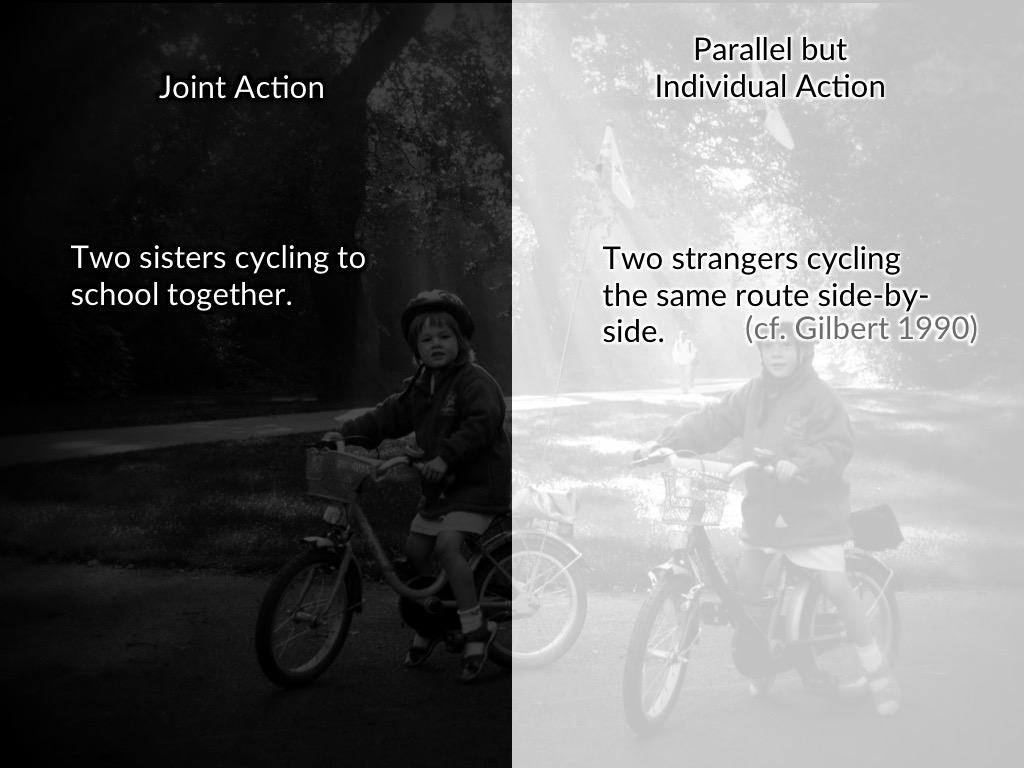

These and other contrasting pairs invite the question, What distinguishes

joint action from parallel but merely individual action?

A natural first thought is that in joint action, our actions are coordinated.

But this turns out not to be a distinguishing feature of joint action because ...

... when two strangers cycle side by side, their actions may need to be highly coordinated

so that they do not crash even if they are merely acting in parallel.

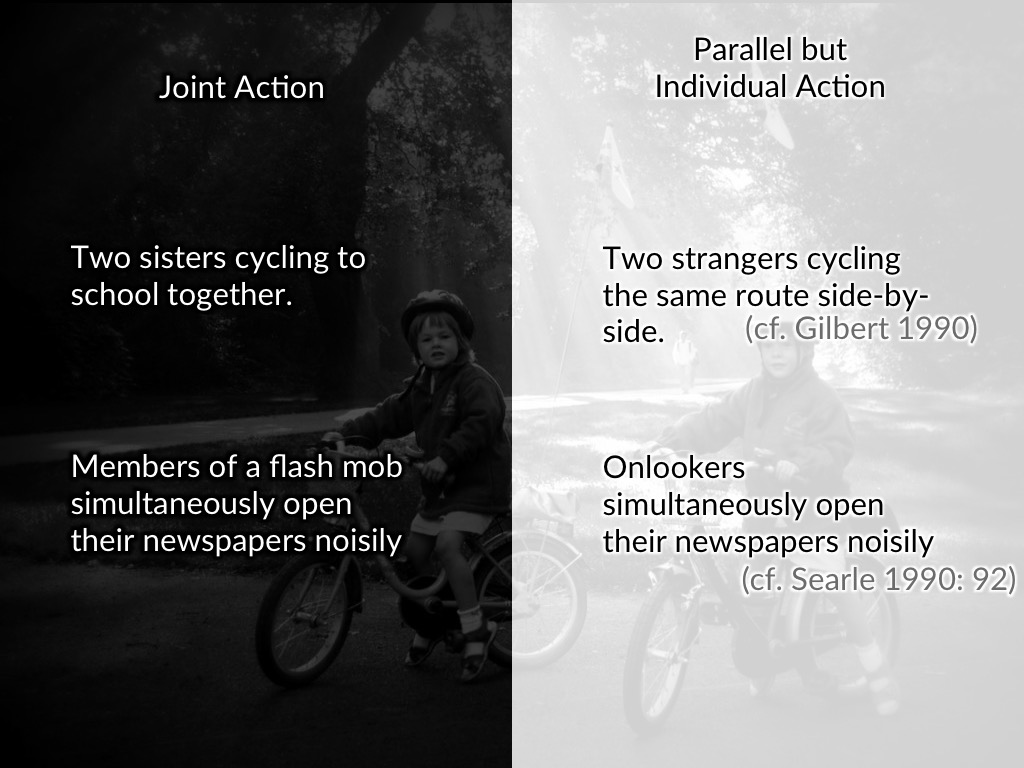

Another idea is that in joint action, our actions have a common effect.

So, for example, when the flash mob open their newspapers, there is a strikingly loud rustle

of paper. None of them individually cause this loud rustle: instead it is a common effect of their

actions.

But consider the actions of the flash mob together with those of the onlookers.

All of these actions have a common effect---the strikingly loud rustle of paper is produced by the

simultaneity of their actions. And this applies to the onlookers who merely happen to open

their newspapers just as the flash mob starts no less than to the members of the flash mob.

So what does distinguish joint action from actions which occur in parallel but are merely individual?

Not coordination, not common effects. So what is it?

[This is just to say that the question, What distinguishes

joint action from parallel but merely individual action? is not straightforward to answer. ]

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

This is the organising question for our project (the project to be investigated in this

series of lectures). Of course there will be lots of further questions, but I like to

have something simple to frame our thinking and this question serves that purpose.

My hope is that by answering this seemingly straightforward question, we will be

in a position to answer the hard question about which forms of shared agency

underpin our social nature.

The first two contrast cases are supposed to show that this question isn’t easy

to answer because the most obvious, simplest things you might appeal to---coordination

and common effects---won’t enable you to draw the distinction.

Aim

An account of joint action must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

This invites us to think in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions.

Of course, there are all kinds of reasons why this might be problematic, and we

will consider many such reasons.

But as I just said, having simple ideas to frame our thinking is good, and that’s why

I take this as my working aim.

(The ultimate aim is a ‘Blueprint for a Social Animal’, but it is difficult to be

precise about what that will involve at this stage.)

So What?

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

A \emph{joint action} is an exercise of shared agency.

Individual vs Aggregate -- both miss shared agency

In philosophy of mind and action, it is normal to focus just on a single individual

who might as well be acting in isolation. But if you think about almost any aspect of

cognition and agency, it is striking that it can’t be fully understood in isolation.

Our capacities for knowledge, emotion and action depend in numerous ways on our

interactions with others.

By contrast with philosophy, many disciplines such as economics and sociology do

treat multiple individuals. But on the whole this involves treating individuals

as indistinguisable from one another.

So once again, on the aggregate perspective, there is no room for shared agency.

There is growing awareness in cognitive science and philosophy that in missing

shared agency we may be missing something that shapes our lives and explains

much about why we humans are the way we are.

Excitingly, new techniques and technologies to investigate shared agency are

being developed too.

At the same time there is an amazing degree of uncertainty and even confusion

among philosophers and theoretically-minded scientists.

It’s not just that there are different theories of shared agency; there is

fundamental disagreement about what sort of conceptual and ontological resources

are needed, and about the questions such a theory should answer.

As you’ll see, there are even two completely unconnected articles on this topic

in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

So we face lots of challenges ...

So here you have the question for this course, our aim and the reason it matters.