Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Collective Goals and Motor Representations

In virtue of what do actions involving multiple agents ever have collective goals?

Very Small Scale

Shared Agency

Small Scale

Shared Agency

Very Small Scale

Shared Agency

Playing a piano duet

Playing a chord together

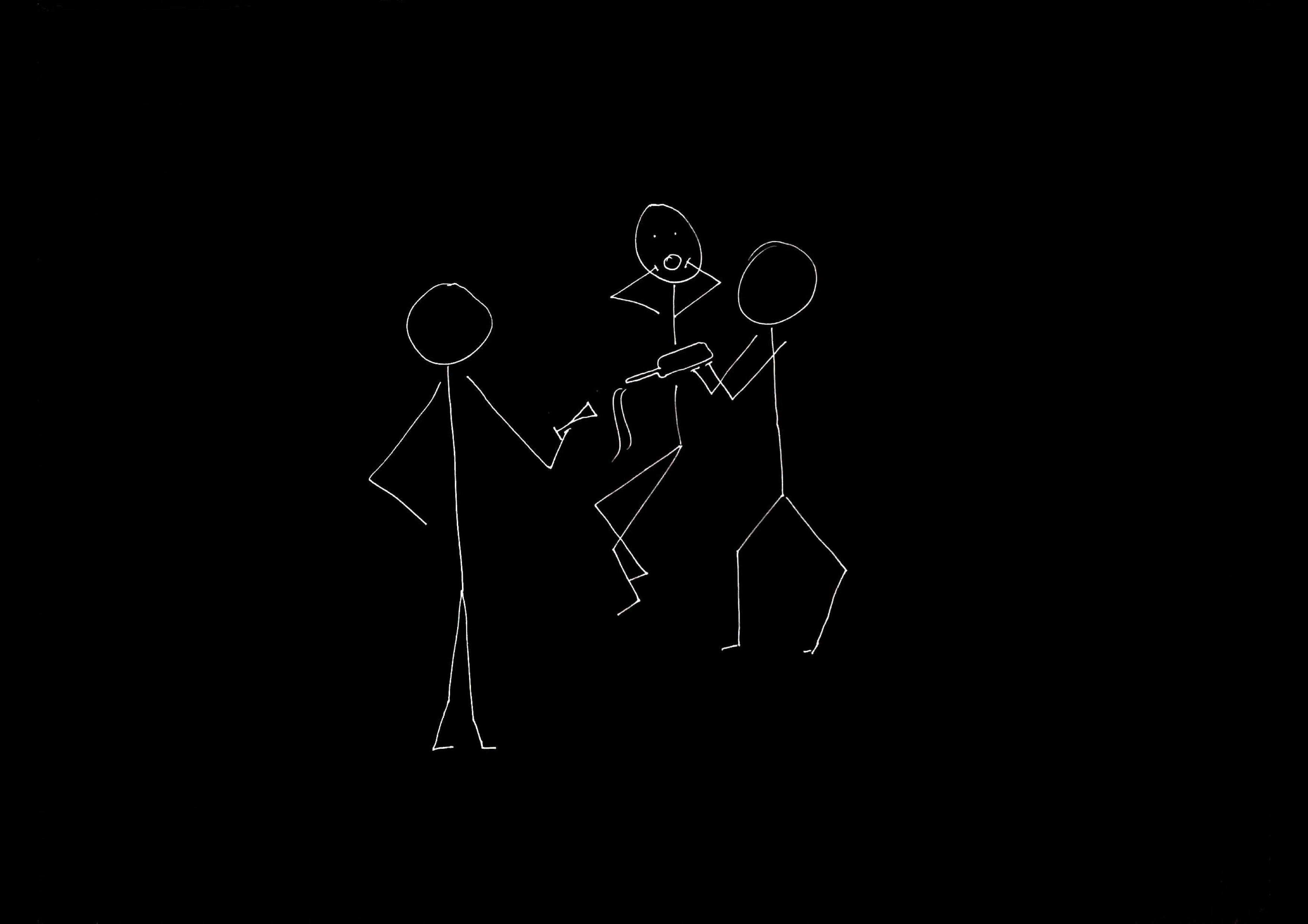

Toasting our success together

Clinking glasses

Washing up together

Passing a plate between us

motor representations represent outcomes and trigger planning-like processes

Conjecture :

collective goals are represented motorically

I.e. sometimes, when two or more actions involving multiple agents are, or need to be, coordinated:

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

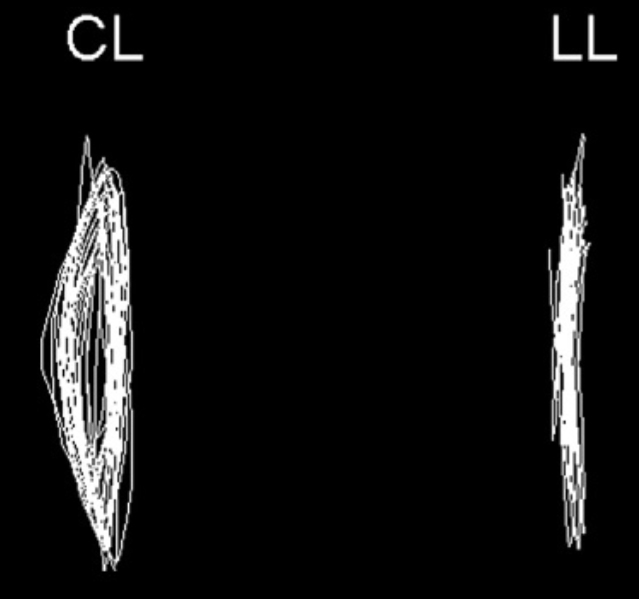

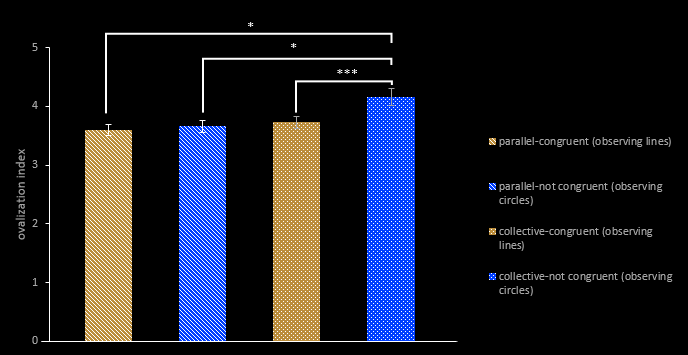

Garbarini et al, 2014 figure 3 (part)

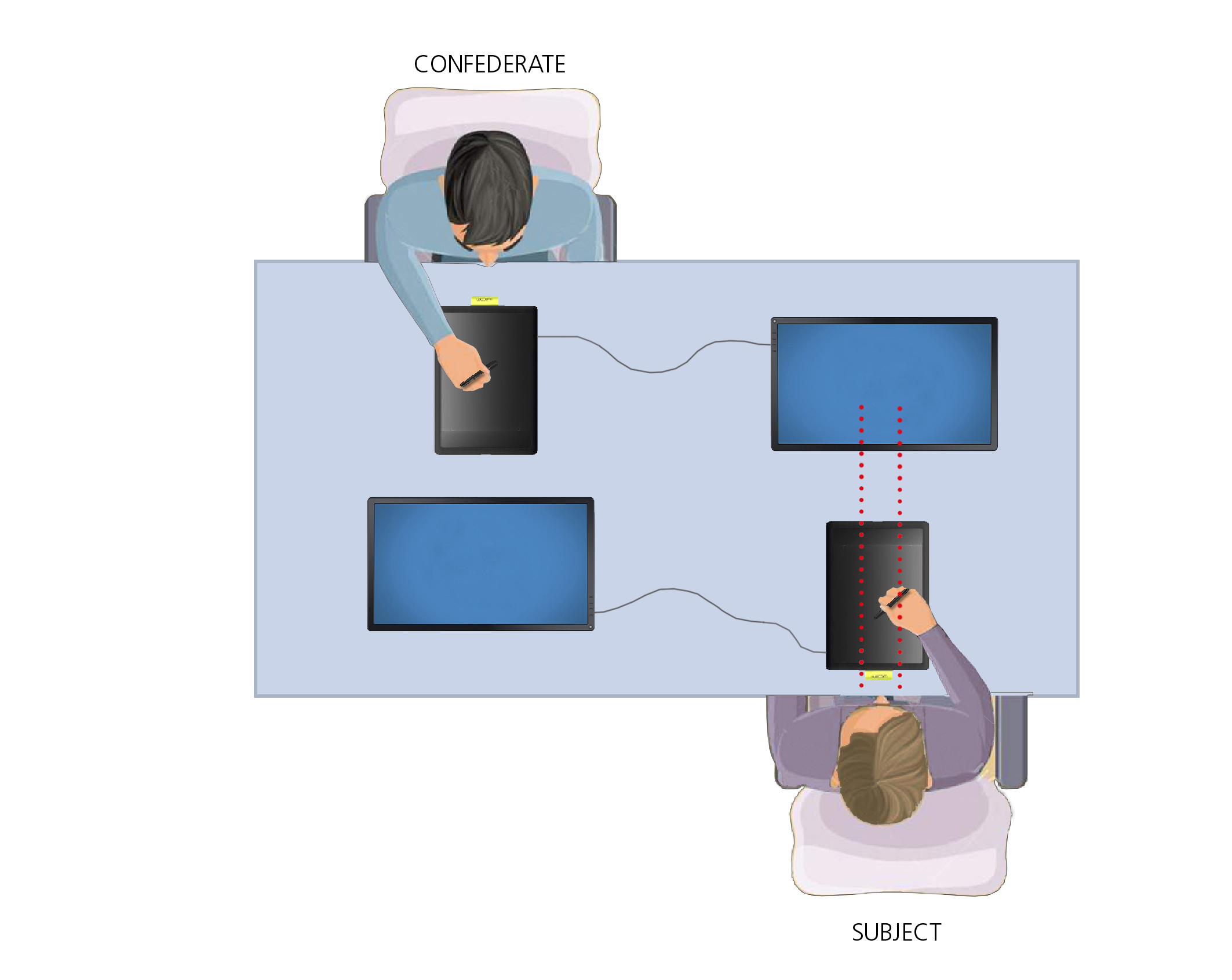

della Gatta et al, ‘Drawn Together’ Cognition 2017

della Gatta et al, ‘Drawn Together’ Cognition 2017

Parallel

“Look at the screen in front of you. You will see either circles or lines drawn by the experimenter [i.e. confederate] sitting in front of you. Look at them while drawing either a circle or a line. While drawing, please don’t lift the pen from the tablet and try to take advantage of the whole drawing area.”

Joint

“You and Gabriele [name of confederate] are old friends who have the collective goal of drawing lines and circles together in order to produce a single design. Look at the screen in front of you. You will see either circles or lines drawn by Gabriele. Look at them while drawing either a circle or a line together with him. While drawing, please don’t lift your pens from the tablet and try to take advantage of the whole drawing area.”

Conjecture :

collective goals are represented motorically

I.e. sometimes, when two or more actions involving multiple agents are, or need to be, coordinated:

- Each represents a single outcome motorically, and

- in each agent this representation triggers planning-like processes

- concerning all the agents’ actions, with the result that

- coordination of their actions is facilitated.

In virtue of what do actions involving multiple agents ever have collective goals?

cooperation?

Purposive actions are cooperative to the extent that, for each agent, her performing these actions rather than any other actions depends in part on how good an overall pattern of trade-offs between demandingness and well-suitedness can be achieved for all of the actions.

Where we each represent a collective goal motorically, our actions will normally be cooperative in this sense.

Limit: very small scale joint actions